Interior Least Tern (Sterna antillarum athalassos)

TPWD ©

- Other Names

- Least Tern

- Texas Status

- Endangered

- U.S. Status

- Endangered, Listed 6/27/1985

- Description

- Least Terns are the smallest North American terns. Adults average 8 to 10 inches in length, with a 20 inch wingspan. Their narrow, pointed wings make them streamlined flyers. Males and females are similar in appearance. Breeding adults are gray above and white below, with a black cap, black nape and eye stripe, white forehead, yellow bill with a black or brown tip, and yellow to orange legs. Hatchlings are about the size of pingpong balls and are yellow and buff with brown mottling. Fledglings (young birds that have left the nest) are grayish brown and buff colored, with white heads, dark bills and eye stripes, and stubby tails. Young terns acquire adult plumage after their first molt at about 1 year, but do not breed until they are 2 to 3 years old. The Least Tern's call has been described as a high pitched "kit,""zeep," or "zreep."

- Life History

- Interior Least Terns arrive at breeding areas from early April to early June, and spend 3 to 5 months on the breeding grounds. Upon arrival, adult terns usually spend 2 to 3 weeks in noisy courtship. This includes finding a mate, selecting a nest site, and strengthening the pair bond. Courtship often includes the "fish flight", an aerial display involving aerobatics and pursuit, ending in a fish transfer on the ground between two displaying birds. Courtship behaviors also include nest preparation and a variety of postures and vocalizations.

Least Terns nest in colonies, where nests can be as close as 10 feet but are often 30 feet or more apart. The nest is a shallow depression in an open, sandy area, gravelly patch, or exposed flat. Small twigs, pieces of wood, small stones or other debris usually occur near the nest.

Egg-laying begins in late May, with the female laying 2 to 3 eggs over a period of 3 to 5 days. The eggs are pale to olive buff and speckled or streaked with dark purplishbrown, chocolate, or blue-gray markings. Both parents incubate the eggs, with incubation lasting about 20 to 22 days. The chicks hatch within one day of each other and remain in the nest for about a week. As they mature, they begin to wander from the nest, seeking shade and shelter in clumped vegetation and debris. Chicks are capable of flight within 3 weeks, but the parents continue to feed them until fall migration. Least Terns will renest until late July if clutches or broods are lost.

Activities of the Interior Least Tern during the breeding season are limited to the portion of river near the nesting site. Nesting adults defend an area surrounding the nest (territory) against intruders, and terns within a colony will defend any nest within that colony. When defending a territory, the incubating bird will fly up giving an alarm call, and then dive repeatedly at the intruder

The breeding season is usually complete by late August. Prior to migration, the terns gather at staging areas with high fish concentrations. They gather to rest and eat prior to the long flight to southern wintering grounds. Low, wet sand or gravel bars at the mouths of tributary streams and floodplain wetlands are important staging areas. Interior Least Terns often return to the same breeding site, or one nearby, year after year.

Nesting success of terns at a particular location varies greatly from year to year. Because water levels fluctuate and nesting habitats such as sandbars and shorelines change over time, the terns are susceptible to habitat loss and frequent nest and chick loss.

The Interior Least Tern is primarily a fish-eater, feeding in shallow waters of rivers, streams, and lakes. The birds are opportunistic and tend to select any small fish within a certain size range. Feeding behavior involves hovering and diving for small fish and aquatic crustaceans, and occasionally skimming the water surface for insects.

In portions of the range, shorebirds such as the Piping and Snowy plovers often nest in close proximity. The Piping Plover is listed as Threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. - Habitat

- Nesting habitat of the Interior Least Tern includes bare or sparsely vegetated sand, shell, and gravel beaches, sandbars, islands, and salt flats associated with rivers and reservoirs. The birds prefer open habitat, and tend to avoid thick vegetation and narrow beaches. Sand and gravel bars within a wide unobstructed river channel, or open flats along shorelines of lakes and reservoirs, provide favorable nesting habitat. Nesting locations are often at the higher elevations away from the water's edge, since nesting usually starts when river levels are high and relatively small amounts of sand are exposed. The size of nesting areas depends on water levels and the extent of associated sandbars and beaches. Highly adapted to nesting in disturbed sites, terns may move colony sites annually, depending on landscape disturbance and vegetation growth at established colonies.

For feeding, Interior Least Terns need shallow water with an abundance of small fish. Shallow water areas of lakes, ponds, and rivers located close to nesting areas are preferred.

As natural nesting sites have become scarce, the birds have used sand and gravel pits, ash disposal areas of power plants, reservoir shorelines, and other manmade sites. - Distribution

There are three subspecies of the Least Tern recognized in the United States. The subspecies are identical in appearance and are segregated on the basis of separate breeding ranges. The Eastern or Coastal Least Tern (Sterna antillarum antillarum), which is not federally listed as endangered or threatened, breeds along the Atlantic coast from Maine to Florida and west along the Gulf coast to south Texas. The California Least Tern (Sterna antillarum browni), federally listed as endangered since 1970, breeds along the Pacific coast from central California to southern Baja California. The endangered Interior Least Tern (Sterna antillarum athalassos) breeds inland along the Missouri, Mississippi, Colorado, Arkansas, Red, and Rio Grande River systems. Although these subspecies are generally recognized, recent evidence indicates that terns hatched on the Texas coast sometimes breed inland. Some biologists speculate that the interchange between coastal and river populations is greater than once thought.

There are three subspecies of the Least Tern recognized in the United States. The subspecies are identical in appearance and are segregated on the basis of separate breeding ranges. The Eastern or Coastal Least Tern (Sterna antillarum antillarum), which is not federally listed as endangered or threatened, breeds along the Atlantic coast from Maine to Florida and west along the Gulf coast to south Texas. The California Least Tern (Sterna antillarum browni), federally listed as endangered since 1970, breeds along the Pacific coast from central California to southern Baja California. The endangered Interior Least Tern (Sterna antillarum athalassos) breeds inland along the Missouri, Mississippi, Colorado, Arkansas, Red, and Rio Grande River systems. Although these subspecies are generally recognized, recent evidence indicates that terns hatched on the Texas coast sometimes breed inland. Some biologists speculate that the interchange between coastal and river populations is greater than once thought.

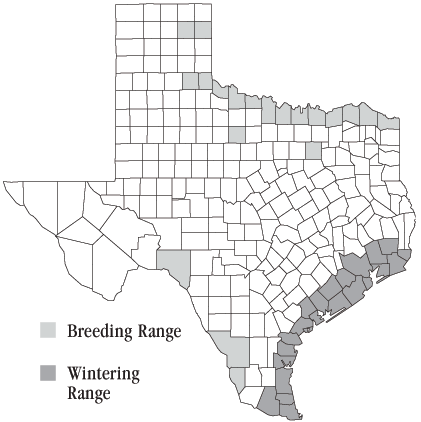

The Interior Least Tern is migratory, breeding along inland river systems in the United States and wintering along the Central American coast and the northern coast of South America from Venezuela to northeastern Brazil. Historically, the birds bred on sandbars on the Canadian, Red, and Rio Grande River systems in Texas, and on the Arkansas, Missouri, Mississippi, Ohio and Platte River systems in other states. The breeding range extended from Texas to Montana and from eastern Colorado and New Mexico to southern Indiana. It included the braided rivers of Oklahoma and southern Kansas, salt flats of northwest Oklahoma, and alkali flats near the Pecos River in southeast New Mexico.

Today, the Interior Least Tern continues to breed in most of the major river systems, but its distribution is generally restricted to the less altered and more natural or little disturbed river segments. In Texas, Interior Least Terns are found at three reservoirs along the Rio Grande River, on the Canadian River in the northern Panhandle, on the Prairie Dog Town Fork of the Red River in the eastern Panhandle, and along the Red River (Texas/Oklahoma boundary) into Arkansas.- Threats and Reasons for Decline

- Channelization, irrigation, and the construction of reservoirs and pools have contributed to the elimination of much of the tern's natural nesting habitat in the major river systems of the Midwest. Discharges from dams built along these river systems pose additional problems for the birds nesting in the remaining habitat. Before rivers were altered, summer flow patterns were more predictable. The nesting habits of the Least Tern evolved to coincide with natural declines in river flows. Today, flow regimes in many rivers differ greatly from historic regimes. High flow periods may now extend into the normal nesting period, thereby reducing the availability of quality nest sites and forcing terns to nest in less than optimum locations. Extreme fluctuations can inundate potential nesting areas, flood existing nests, and dry out feeding areas.

Historical flood regimes scoured areas of vegetation, providing additional nesting habitat. However, diversion of river flows into reservoirs has resulted in encroachment of vegetation and reduced channel width along many rivers, thereby reducing sandbar habitat. Reservoirs also trap much of the sediment load, limiting formation of suitable sandbar habitat.

In Texas and elsewhere, rivers are often the focus of recreational activities. For inland residents, sandbars are the recreational counterpart of coastal beaches. Activities such as fishing, camping, and ATV use on and near sandbar habitat are potential threats to nesting terns. Even sand and gravel pits, reservoirs, and other artificial nesting sites receive a high level of human use. Studies have shown that human presence reduces reproductive success, and human disturbance remains a threat throughout the bird's range.

Water pollution from pesticides and irrigation runoff is another potential threat. Pollutants entering rivers upstream and within breeding areas can adversely affect water quality and fish populations in tern feeding areas. Least Terns are known to accumulate contaminants that can affect reproduction and chick survival. Mercury, selenium, DDT derivatives, and PCBs have been found in Least Terns throughout their range at levels warranting concern, although reproductive difficulties have not been observed.

Finally, too little water in some river channels may be a common problem that reduces the birds' food supply and increases access to nesting areas by humans and predatory mammals. Potential predators include coyotes, gray foxes, raccoons, domestic dogs and cats, raptors, American Crows, Great Egrets, and Great Blue Herons. - Ongoing Recovery

- State, federal, and private organizations throughout the United States are collaborating to census the birds, conduct research, curtail human disturbance, and provide habitat. Continued monitoring of confirmed and potential colony sites is underway to assess population status and reproductive success. Protective measures, including signs and fences, are being implemented to restrict access to sites most threatened by human disturbance. Vegetation control at occupied sites, chick shelter enhancement, predator control, pollution abatement, and habitat creation/restoration at unoccupied sites are management strategies used to benefit Interior Least Tern populations.

Biologists continue to assess habitat availability and quality throughout the bird's range in Texas, and identify essential habitat for management and protection. Recently, in a cooperative effort between the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, National Park Service, International Boundary and Water Commission, Comision Internacional de Limites y Aguas, Oficina de Ecologia Estado de Coahuila, and City of Del Rio, warning signs in both Spanish and English were erected to inform visitors about the effects of human disturbance on the terns. Also, the National Park Service recently initiated annual status surveys for Interior Least Terns at Amistad NRA. Finally, public information campaigns concerning Least Tern conservation are a vital part of the recovery process.