Sea-Beans

Endless waves wash against our coastal beaches leaving behind brightly colored or unusual seashells to catch the collector’s eye, but those same waves also bring other gifts from the sea. Among the many interesting objects left stranded on the sand are tropical seeds and fruits that drift here from such exotic places as the west coast of Africa, the Amazon Basin, South America, Central America, and the islands of the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico.

Few people can resist the urge to pick up brightly colored seashells, but the waves that wash our shores also bring other interesting objects for the sharp-eyed collector. This assortment of tropical drift seeds and fruits represents many hours of beachcombing pleasure along the Texas coast. Sea-beans are most abundant from late March into early summer, but you must look closely to find them. Many are covered with barnacles and other marine debris.

Specimens shown in these photographs are from a private collection, but all were found on Texas beaches. When they were picked up, many were covered with barnacles and other debris, so don’t expect to find them all shiny and clean. The best sea-bean collecting on any Gulf Coast beach within the United States is at Padre Island. From late March into early summer is the best time to find a large number of them; however, an occasional specimen can be found at any time of the year.

Next time you visit the coast, pay close attention to objects lying on the beach and you may be able to start a sea-bean collection of your own. Additional information about this subject can be found in the book World Guide to Tropical Drift Seeds and Fruits by C. R. Gunn and J. V. Dennis.

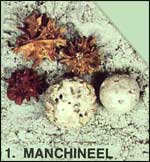

1. Dense thickets of manchineel trees, growing along the coasts of tropical islands in the Caribbean Sea and along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of Central America and northern South America, produce crabapplelike fruits that drift to our shores. The outer skin erodes quickly in the ocean to expose a corky fruit layer. Many specimens arrive here in this form. When the corky layer erodes or is removed, a sculptured seed pod, highly prized by collectors, is exposed. All parts of the machineel tree are extremely poisonous, with the poison concentrated in a milky juice. Contact with the juice will blister the skin, but fortunately none remains in the fruit by the time it makes its journey to Texas.

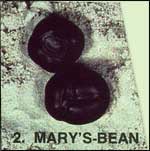

2. The woody vine that produces the Mary’s-bean is a member of the Guatemalan wet- or mixed-forest flora. This relative of the morning glory also grows in Mexico and the West Indies. The black bean appears to be divided into four parts, but it actually contains only one seed. Since the dividing indentation resembles a cross, early Christians gave special significance to this bean and called it Mary’s-bean for the Blessed Mother. It is also known as the crucifixion-bean.

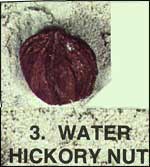

3. Seeds of plants native to the United States also drift in with the tropical specimens. One such native is the water hickory nut. It probably was brought into the Gulf waters by the Mississippi River and can remain buoyant for more than eight months.

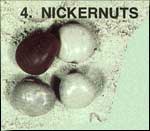

4. A native of southeast Asia, the gray nickernut is produced on spiny, trailing shrubs that form dense thickets just beyond the high tide zone. Since they are located so close to water, it is not surprising that nickernuts are very common drift seeds. Residents of the Hebrides Islands believed these long-ranging seeds possessed magical powers and wore them to ward off the Evil Eye. They believed the seeds would turn black to warn the wearer of harm. In Jamaica the seeds were used as medicine, worn as coat buttons, and substituted for marbles. In fact, another name for marble is nicker. The brown bean with similar concentric lines is probably a member of the same genus or a closely related one.

5. Another Asian seed that makes its way to Texas is the sea purse or saddle-bean. This traveler is able to remain buoyant for at least two years. Its tan and dark brown mottled surface can be polished, so the sea purse often is used in making sea-bean jewelry.

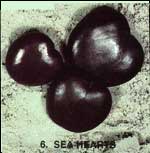

6. A high-climbing, woody, tropical vine from the Caribbean produces the large sea heart seeds in four- to seven-foot, twisted fruit pods. Each pod contains ten to fifteen seeds enclosed in individual compartments. These compartments are quite fragile and seldom endure a trip across the water, but the sea heart seeds have an extremely hard coating and can remain buoyant for at least two years. They, too, can be polished and are used extensively for making curio jewelry.

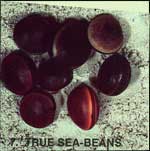

7. Several species of the group known collectively as true sea-beans drift to us from the Caribbean. Their colors range from tan to reddish brown to almost black; however, all species have a dark band that does not completely encircle the circumference. This band gives the appearance that the shell is hinged at the back where the band does not meet. True sea-beans also are known as horse eye-beans.

8. Native to tropical America and the West Indies, the prickly palm, also known as the corozo palm, can be distinguished from other palms by the three pores that are located equal distances apart around the middle of the seed. Buoyancy occurs as the inner seed decays.

9. Starnut palms, or black palms, also are native to tropical America and the West Indies, but their seeds are more oblong—rounded at the base and pointed at the other end. The surface has numerous light-colored markings that radiate from the pores at the base. As with the prickly palms, buoyancy, which occurs when the inner seed decays, lasts about two years.

10. The black walnut (right), native to the United States, is transported by rivers into the Gulf, where it is cast upon the beach along with tropical specimens. The Jamaican walnut (left) drifts here from the Caribbean. Rounder than the more compressed black walnut, the Jamaican walnut has a flatter, broader base and is not as pointed at the other end.

11. Tangled masses of tropical beach vines produce the small colorful bay-beans. These legumes grow in pods similar to those of native beans. The outside covering of the bean will not permit water to enter for at least one and a half years.

12. The trinervius seed is produced by a woody vine native to the area from southern Mexico to western Colombia. The hilum (scar that marks its point of attachment) is lighter and has raised edges. The trinevius can remain buoyant for at least six months.

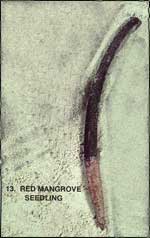

13. The red mangrove specimen, often called the sea pencil, actually is a seedling that drops into the ocean or swamp waters from the parent tree and is automatically planted or washed away. Since it floats upright in the water, it may take root and grow if the underwater point buries itself in sand or silt.

14. The dark, grainy-surfaced seeds of the Jamaican navel spurge grow tightly packed in orange-sized, hard-shelled fruits and are freed when the fruits rupture. The plant grows in thickets near beaches, tidal swamps, or rivers, and seeds that reach the ocean may drift our way. The seed coat is quite brittle, so few stranded seeds are found in an undamaged condition.

15. Native to the New World tropics is the crabwood tree, which is a member of the same family as the mahogany. The outer portion of its large seed is composed of hard cells that give it durability while it is drifting.

16. From the inlands of southern Mexico, the fruit of the Andira Galeottiana, a small native tree, is carried by rivers to the Gulf. The specimen, adorned with barnacles still has its protective outer coating, but the other one has been scoured down to its fibrous layer during its travels to our coast.

Ilo

Hiller

1983 Sea-Beans. Young

Naturalist. The Louise

Lindsey Merrick Texas Environment

Series, No. 6, pp. 98-101.

Texas A&M University

Press, College Station.