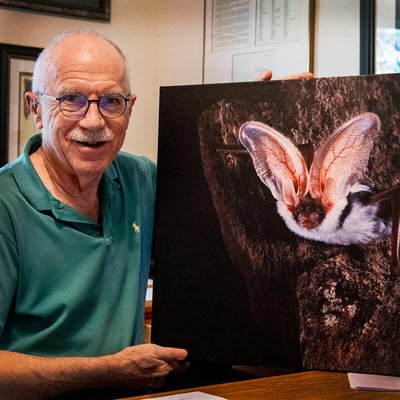

Big Bat Daddy Merlin Tuttle

Bats are enigmatic nocturnal flying mammals. There are over 14-hundred species that we know of worldwide, 33 of which are known to live in Texas. Many are threatened. And Dr. Merlin Tuttle--part Indiana Jones and part Bill Nye the Science Guy--has led the bat conservation charge worldwide.

Big Bat Daddy Merlin Tuttle

Season 2 Episode 13

UTTS: S2E13: Big Bat Daddy Merlin Tuttle

[MUS—A DAINTY FLOWER]

Bats are enigmatic nocturnal flying mammals. There are over 14-hundred species that we know of worldwide, 33 of which are known to live in Texas.

Over the centuries—with a few notable exceptions—people have viewed bats as demonic, blood-sucking, hair nesting spreaders of disease and pestilence. This thinking led to the mass slaughter of bats worldwide up until the mid-20th Century. Although some misguided killing continues today.

The truth about bats is this: they have no demonic affiliation—never have—and couldn’t care less about your hair…your hemoglobin…or your health.

Fortunately, the fear-based thinking around bats started to change when a passionate bat biologist—enigmatic in his own right, but whom we’ve seen casting a shadow in daylight hours—came onto the scene and started revealing truths about bats that surprised even the most respected bat biologists of the time.

Who is he?

[SFX—I’M BATMAN]

Not exactly…but he is a crusader when it comes to this group of animals that makes up one-fifth of Earth's total mammalian population. Wanna meet him? Then, stay with us.

[MUS—HOWDY]

From Texas Parks and Wildlife…this is Under the Texas Sky …a podcast about nature…and people… and the connection they share…I’m Cecilia Nasti.

[MUS—BEER BOTTLE MUSIC]

I guess you could call Dr. Merlin Tuttle the Big Bat Daddy.

[MERLIN TUTTLE] A lot of people have referred to me as the father of modern bat conservation.

I met Merlin …oh gosh…way back in the early 1980s when I was at the beginning of my career in Austin, Texas …and shortly after he founded Bat Conservation International—BCI for short.

I was like a lot of people at the time—skeptical about the value of what I considered to be flying rodents. Truth is, bats aren’t even remotely related to rodents. They are so unique that scientists placed them in a group all their own, called 'Chiroptera', which means hand-wing. Cool, huh?

Anyway, at the time Merlin began his career in formal bat conservation, bats had just been ranked between rattlesnakes and cockroaches in a national public opinion poll. And to be clear—that means they were highly unpopular.

Good thing he likes a challenge, because Merlin Tuttle had his work cut out for him. He’s worked tirelessly for these fascinating mammals for nearly his entire career (over 60 years now!). Most conservation organizations that deal with bats today started because of his early efforts.

Last spring, I had a little reunion of sorts with Merlin; the sight of him all these years later still conjures images of Indiana Jones. He may be older and a little slower, but he remains ageless when talking passionately about his life’s work.

He lives in west Austin these days—the front rooms of his home serve as headquarters of Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation, a non-profit he founded in 2014, after stepping down from 30 years of leadership at BCI. Just proves that you can’t keep a good bat man down.

[MUS—BATMAN THEME MUSIC]

[CECILIA NASTI & MERLIN TUTTLE]

[CECILIA] What was it about bats that first intrigued you? Is this a lifelong interest?

[MERLIN] Lifelong I’ve been interested in anything that’s alive and wiggles. Even plants that don’t wiggle [laughs]. But, uh, I’ve been interested in living things and nature all my life. I got particularly interested in bats when, in high school, a friend told me about a bat cave not far from my home. And I convinced my father to take me over there. And, um…we not only found a lot of bats, but I got intrigued at watching them. And saw that they were doing things that they were said not to do in the existing books on the subject.

[MUS—OUR HOME TOWN]

So, what do you do when you are an intelligent, curious, non-driving Knoxville, Tennessee teenager who has observed behaviors in gray bats that contradict the established scientific norm?

[MERLIN] I guess being a little bit brash, I, uh, convinced my mother to take me to the Smithsonian [Institution in Washington D.C.] so that I could meet with the guys that wrote the books and tell them that I was finding things that weren’t in accordance with their reports in their books. And, uh, so we got into the Smithsonian without even an appointment; fortunately, my mother was quite an attractive woman. I think that didn’t hurt me in getting in. Uh…we went to the receptionist and asked for um, opportunity to meet with, uh, Dr. Charlie Hanley who was head of the mammal division—I knew that much. And, uh, I was amazed. He came right down, and he took off almost a half a day to show me around the bat collections and teach me about bats and introduce me to Fish and Wildlife Service staff who were in charge of bat banding in America at the time. And I had brought a voucher specimen with me, so they knew that I knew what I was talking about that yes, indeed, this was a gray bat. And explain to them…and show them my field notes that I had been keeping on what the bats did and why I believed they were migratory when the book said the bats lived in one cave year-round. And, so they were naturally fairly impressed with a high school student that comes in with field notes and voucher specimens and tells them that he’s found something different that what’s reported in their books.

[CECILIA] These are adults who’ve spent their whole lives studying these things. And here, a high school student comes in and you’re turning things on their head.

[MERLIN] That’s true, but I had really good notes, and well-prepared specimens and they could tell that I probably knew what I was talking about.

[MUS-AMERICANA DREAMING]

Clearly, the elder scientists thought highly of young Merlin—and sent him back to Tennessee with thousands of bat bands and instructions on how use them.

[MERLIN] So, they issued me thousands of bat bands, and said ‘Why don’t you go put bands on these bats and see if you can figure out where they go.’ And I got incredibly lucky; I only banded a few hundred at first. But, uh, those bats were rediscovered by me—I think it was less than two months later—more than a hundred miles north in a cave where they were hibernating. And I had caught them, it turned out, in a migratory stopover cave on their way north. Now, the last thing we would have expected if they were migrating… we’d have thought that were going south. I mean, isn’t that what animals do in the winter? And, uh, so, it was such a surprise when I found my banded bats a hundred miles north, just by incredible accident. I mean, I was just going out in Hillbilly country and stopping—again I wasn’t old enough to be driving a car or anything—so I’d go with my father…we’d go into old country stores with a potbelly coal burning stove and on a weekend and ask if any of the old geezers around the stove knew about any bat caves in the area. I was just interested in finding bats and studying bats in general. And so, finally we heard about this cave that turned out to have my banded bats in it. So, when we went to look at the reported bats, we found tens of thousands of them. I mean it was something I’d never, ever seen. I’d never seen more than maybe a few hundred or—certainly in hibernation I hadn’t seen that many…

[CECILIA] Were these all the same species?

[MERLIN] Yes. These were all gray, gray bats. And, uh, so, I saw that a number of them were banded, but I was so sure that they couldn’t be mine—I mean, after all, I couldn’t be that lucky. Uh, I carefully wrote down the band numbers and got ready to go home and report them to Fish and Wildlife Service to see who had banded them. Well, I got home, and to my amazement they were my band numbers!

Let that sink in a minute.

[MUS—WANDERING THOUGHTS]

When he was in high school, Merlin Tuttle discovered something about gray bats that until then had been misrepresented as fact in reputable science texts. He found that contrary to published research by notable scientists, gray bats were, in fact, migratory, and did not live in one cave year-round as previously believed. Discovering bats that he had banded in another cave about a hundred miles away proved it.

Moreover, he found that they had travelled north instead of south per usual migration patterns. That’s heady stuff for a young man who had to have his parents drive him around so he could make his observations and conduct his research.

[MERLIN & CECILIA]

[CECILIA] So, was this when you were really hooked, then?

[MERLIN] Well, this certainly began to set the hook. And, uh, over time, as I started getting more returns from people finding the bats other than just myself, uh, it expanded and eventually I banded 41-thousand bats and tracked them for 20 years and it became my doctoral thesis. What I learned in tracking their movements and studying the various effects of living in different kinds of situations... So, uh…just a curious adventure as a high school student turned out to be literally my life work.

[MUS—QUIETLY GIFTED]

The thought that runs through my mind is this: Where would the state of bat conservation be today if Dr. Merlin Tuttle’s parents hadn’t made the choice to drive him throughout Tennessee to scope out bat caves, or to drive the nearly thousand mile round-trip from their home in Knoxville to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, to meet with bat scientists, when he was a motivated and curious high school student? That’s something, isn’t it?

When I got to know bats, I learned to love bats; you will, too. Get started at a state park or natural area with bat viewing. Even urban areas like Austin, with its 1.5 million migratory Mexican free-tailed bats emerging from under the Ann Richards Bridge is breathtaking.

The best time to see them is spring through fall, with the most awe-inspiring emergences happening in late July and August once the bat pups begin to take flight.

You can also check in with Merlin on his website www.merlintuttle.org for research on bats and amazing bat photography by the good doctor, himself.

Log into the Texas Parks and Wildlife website, too, for information about bat species in Texas and which Texas State Parks offer the best bat viewing opportunities.

I want to encourage you to get involved with the podcast by letting us know the things you want to hear about. Just click on the Get Involved link at Underthetexassky.org…leave us a message and we’ll be in touch.

[MUS—ORBIT YOUR SOUL]

And so, we come to the end of another podcast. Under the Texas Sky is a production of Texas Parks and Wildlife and is available at UndertheTexasSky.org or wherever you get your podcasts.

Speaking of where you get your podcasts…we’d love it if you’d leave a review and let us know how we’re doing.

We record the podcast at The Block House in Austin, Texas. Joel Block does our sound design.

We receive distribution and web help from Susan Griswold and Benjamin Kailing.

I’m your producer and host, Cecilia Nasti, reminding you that life’s better outside when you’re Under the Texas Sky.

Join us again next time for Under the Texas Sky.

[06—MERLIN] So, I’d go with my father, and we’d go into old country stores with a potbelly coal burning stove on a weekend and ask if any of the old geezers around the stove knew about any bat caves in the area.