Spring 2008 A publication of the Wildlife Diversity Program—Getting Texans Involved

Texas Plant Conservation:

Issues and Challenges

By Flo Oxley

What animals come to mind when you read the words: Rare. Threatened. Endangered. Extinct? Many people say the dodo or the dinosaurs. Some people say panda bear or Siberian tiger. Still others say the grey wolf, American eagle, or the Texas horned lizard.

Now, what plants come to mind when you read the words: Rare. Threatened. Endangered. Extinct? If you're like most people, a complete blank comes to mind. The vast majority of people can name rare animals, but most people are unable to think of a single plant. That's one of the challenges facing plant conservation in Texas.

Globally, botanists have identified between 250,000 and 300,000 plant species. Many botanists believe that there are at least 300,000 plant species waiting to be discovered and identified. That's a lot of plants! It is estimated that anywhere from 10-29% of these plant species are at risk of extinction as you are reading this. That works out to be 30,000-87,000 plants species facing extinction at any given moment. That's a lot of plants, too. Add to these numbers the estimate that one species (both plants and animals) goes extinct every hour and you can see why the Earth's biodiversity is in trouble.

Looking at this issue from the local level, Texas is home to 5,000-6,000 species of native plants. As a state, we're responsible for the conservation of approximately a quarter (25%) of the North American native flora. Of that number, the USFWS has listed 23 plant species as endangered, 5 as threatened, and more than 200 plant species as "Species of Concern (SOC)." These SOCs are plants that we simply do not have enough information about to make a good decision about their conservation. This lack of information is another of the challenges for plant conservation in Texas. While it may not seem like large numbers of plants are federally listed, Texas is considered one of the most threatened reservoirs of plant and animal life on Earth. It has been identified by the Center for Plant Conservation (CPC) as a "biodiversity/conservation hotspot."

So, what, exactly, are the threats to Texas native plant species? Habitat destruction and fragmentation is, perhaps, the largest threat to our native species. The population in Texas is on the rise. It is estimated that by 2040, more than 26 million people will live in the Lone Star State. These people will need places to live. As a result, urbanization will continue to rise as we build homes and shopping centers to meet the needs of an increasing population. We'll also have to feed those folks. This will mean an increase in farming and ranching to provide a steady food supply. These activities result in loss of habitat.

Recreation and over collection in the wild are two more threats to our native plant species. While not intentional, people who play in the outdoors often destroy habitat. They can inadvertently mow down the very plants that we are trying to protect. Overcollection in the wild is quickly becoming a major concern for plant conservationists. Cacti, which are very popular with plant enthusiasts and collectors, are being dug up and sold in nurseries and on the Internet. Entire populations of a particular species can be wiped out in a single day as a result of these activities.

Plant blindness, a recently discovered phenomenon, also threatens our native plant species. Plant blindness is simply the inability of people to see or notice the plants around them. Plants form a kind of "green noise" that we all tend to overlook. It's the attitude that plants are always there; they've always been there; and, they will always be there. So, why worry?

These are just some of the challenges we face in the conservation of our native plant species. Another challenge is funding for plant conservation. Of all the species listed by the USFWS, both plants and animals, 61% are plant species. Only 5% of the funding allocated by the federal government is earmarked for plant conservation.

There are success stories to celebrate in Texas. For example, Frankenia johnstonii, a federally listed endangered species, has been proposed for delisting. Hard work by Texas Parks and Wildlife botanists revealed that there are many more populations of this species than previously thought. As a result, it is no longer considered endangered.

Texas is a partner in the global conservation initiative that is called the Millennium Seed Bank Project (MSBP). The MSBP began partnering with plant conservationist around the world in 2000 to collect 10% of the world's temperate flora by 2010. The Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center became a partner in 2002 and is now collecting seeds of Texas species throughout the state with the help of private landowners, federal agencies, and nonprofits like the Mercer Arboretum and Botanic Gardens in Humble, Texas.

What can you do to help? Begin by educating yourself. There are many ways to accomplish this. Check out the following websites:

- Endangered and Threatened Species found in Texas

- USDA Threatened and Endangered Plants database

- Center for Plant Conservation, National Collection of Endangered Plants

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service threatened and Endangered plants and wildlife (PDF document)

- Plant Conservation Alliance

Take a class, attend a lecture, or sign up for a conference/symposium on plant conservation. The Texas Plant Conservation Conference is an annual meeting that focuses on Texas' rare plants. This year it is scheduled for September 16-20 and will be held in Corpus Christi.

Don't be afraid to ask questions. Plant conservation botanists are some of the most generous people in the world. We love to talk about our babies and the work we are doing.

If you see an endangered plant being sold in a nursery, ask the manager where they got it. Did they collect it from the wild? Grow it from seed? If they are unwilling to answer your questions, leave and don't go back.

Get involved. Participate in meetings where endangered issues are discussed. Join an organization that works with endangered species issues. There are great ones, including:

- Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center

- Native Plant Society of Texas

- Center for Plant Conservation

- Plant Conservation Alliance

Look at the Federal Register, and make comments on proposals relating to endangered species.

If we all work together and do a little bit each time, we can make a huge difference for the conservation of our irreplaceable natural heritage.

Flo is Director of Plant Conservation and Education at Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in Austin.

Native Plants,

the Key to Great Wildlife Habitat

By Steve Nelle

Texans have many reasons to brag. One of the things Texas can boast about is our tremendous bounty of native plants. These trees, shrubs, vines, wildflowers, forbs, grasses, sedges and cacti provide habitat for an amazing array of wildlife species. This rich abundance of wildlife is absolutely dependent on native plants for their survival and well being.

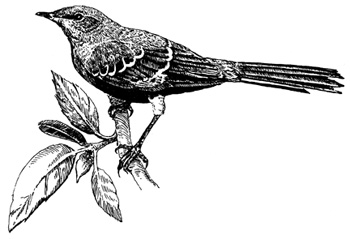

Think about any particular species of wildlife, and begin to consider how many different native plants play a role in their life cycle. Take for example, the mockingbird. First, they need a place to build their nest and conceal it from predators. Trees, shrubs or thickets are used for nest concealment and protection from the elements. The nest itself may be composed of twigs from various bushes as well as the leaf and stem of grasses, catkin tree flowers, fine roots and other plant fiber.

After the young babies are hatched, the parents must find a continuous source of insects to feed the young. These may include grasshoppers, caterpillars, crickets, ants, bees, termites and beetles to name a few. Each of these insects in turn needs a whole host of different plants for their own life requisites.

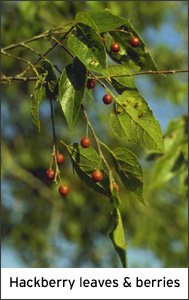

Mockingbirds also eat berries from a host of native plants. These may include hackberry, bumelia, algerita, pokeberry, Virginia creeper, Carolina snailseed, dewberry, mulberry, hawthorn, possumhaw, elbowbush, elderberry or greenbriar. The mockingbird then helps disseminate the seed of these plants by expelling the seed after the soft part of the berry has been digested.

Of course, everyone knows the mockingbird ego; they find the most prominent place possible to perch and sing. Dead trees (called snags), or tall trees with dead limbs provide their favorite perching locations. It would be easy to enumerate over 100 different native plant species that play a role in the life of a single mockingbird.

If this exercise is repeated for each of the bird, mammal, reptile and amphibian species in Texas, it is clear that our diversity of native plant life is essential in maintaining healthy wildlife populations.

The Texas naturalist need not be overwhelmed by this complexity of native plants. Any given tract of land normally has 200 or fewer plant species. Of that number, only about 50 will usually be the more common and important plants. Internet resources, books and local plant experts are all good ways to begin to learn the plants of your area.

And since Texas lands are 95% privately owned, it is plain that stewardship and conservation by landowners is the key to maintaining this rich heritage of plants and animals. Most Texas farmers and ranchers understand their role as caretakers of Texas plant life and wildlife, and take that role seriously. In addition to growing our food supply, and conserving soil and water, Texas landowners manage their land to maintain or restore native plants and wildlife habitat.

Steve is a wildlife biologist with the Natural Resource Conservation Service out of San Angelo.

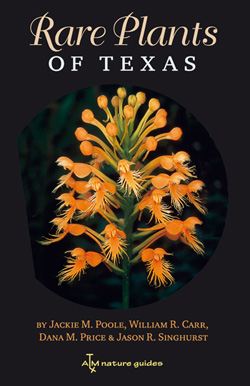

Rare Plants of Texas is highly recommended for anyone concerned with preserving the ecosystems of Texas and the Southwest.

656 pp. • 247 color photos

234 color maps • 215 drawings

$35

How to Write a

Rare Plant Book

in Seven Easy Years

By Jackie Poole

In 2000 when Pat Morton, then head of education and outreach for the Wildlife Diversity Program, approached me about publishing a book on the rare plants of Texas, I was excited. Years before David Riskind and I had written a rare plant identification guide for about 45 species, so how hard could it be to add another 200? Using Poole and Riskind’s 1987 Endangered, Threatened, or Protected Native Plants of Texas and Bill Carr’s abstracts for most of the rare plants in Texas as a starting point, I enlisted Bill and my two botanical co-workers, Jason Singhurst and Dana Price. After a few meetings we had a target list of species and a division of duties. All of us would work on various introductory chapters and species updates, Dana would gather photos and illustrations, Jason would produce maps, Bill would add descriptions and updates to his original work, and I would crack the whip along with helping with everything else, thus violating one of the first rules of project management (never work on the project that you are managing). We also determined that there were quite few species with no photographs or illustrations. With grant money from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, we hired Linny Heagy to produce the exacting and exquisite illustrations that we required. When Linny asked where she could find live plants, we just laughed as most had not been seen in decades. She quickly adapted to using the few dried, flattened, brittle specimens that were available, making them come to life.

We were moving along, taking photographs, reviewing Linny’s illustrations, and updating the species abstracts, when we hit our first speed bump. The press that we had hoped would be our publisher was not interested. The project went into a stall. Then one day Shannon Davies of Texas A&M Press came by our office to discuss possibilities for their Nature Guide series, and she liked our book. We were back in business, and with an editor and publisher.

We went into high gear to get a rough draft finished for preliminary review. In retrospect the draft made burlap seem like silk, but the reviewers liked it enough to recommend that the press publish it. By now it was spring 2004, and I hoped that we could get a final draft to the press by the end of the year. I suppose that I was getting a little aggravated with the project, with continually updating information and adding more species. Somewhere it had to stop.

Of course we didn’t make the 2004 deadline but I was determined that we would finish in 2005. Early in 2005 I hired Emily Lott, a rare combination of botanist and librarian, to compile the glossary of almost 1000 entries and the references with approximately 1500 sources, so large that the computer refused to Spell Check it. We hit our second speed bump in summer 2005 when we were told that many of our digital images were not high enough resolution. We scrambled to find additional photographs that we could use. Throughout 2005 we all worked overtime to complete the book. Jason produced the maps for almost every species (a few do not have precise locations), and Dana spent long hours acquiring permissions from hundreds of photographers, artists, and other publishers. Bill wrote an incredibly detailed chapter on the natural regions of Texas with an emphasis on the rare species in each. And I continued to crack the whip.

On the evening of December 21, the writing was finished, and I spent the next day making electronic and paper copies of the almost 1000 page volume. Just before noon on the 23rd, I handed it all to Shannon. And after that, I felt empty.

The New Year brought a myriad of questions from new editors at the press. The copy edits were delivered in the spring, the peak of any botanist’s field season. But we managed to find hours and days between and sometimes during field trips to address the numerous questions and changes. Then came the calm before the storm, and in the spring field season of 2006, the galley proofs arrived. While they looked beautiful, photographs and illustrations had been cut to provide room for text. We spent another better part of a spring field season, deleting words, lines, and entire paragraphs to be able to add in the all-important photographs and line drawings. After the galley proofs were returned, we waited anxiously.

Shortly before Christmas 2007, we received advance copies. The book was beautiful, if a tad heavy. The black cover with Joe Liggio’s photograph of a brilliant orange orchid was striking. The 25 advance copies that we had for our first book signing at the Wildflower Center were gone within an hour. In mid-January the rest of the copies were loaded off the boat and made it through customs. Books are being shipped to customers and book stores. And all that’s left for us is the signing and to start keeping track of errors and updates for the next version of the book where I hope that someone else will be cracking the whip.

Jackie is a botanist with Texas Parks and Wildlife’s Wildlife Diversity Program in Austin.

We're Under Attack –

Aliens in the Landscape

By Clyde McKinney

Everyone is familiar with big name alien invasives we fear or detest: fire ants, house sparrows, feral hogs, West Nile virus, piranhas, and Africanized honey bees, to name a few. However, what might not be as high-profile, but are equally menacing, are some species of invasive plants.

To understand what an invasive is, it is helpful first to understand just what its antithesis, a native plant, is. Many definitions exist. A simple one is that a native is a plant that was here when the Europeans first arrived. That definition falls a little short, however, because the Native Americans brought in seeds from other areas. Native plants are important because they are properly prepared for and adapted to the conditions in their home. They have learned to withstand the extremes of climate and rainfall specific to that area, thus assuring their continued existence. A native plant lives in harmony with its environment and knows how to survive without causing harm to that environment. Native wildlife is dependent upon native plants for food, habitat, and its very existence.

What native plants are not prepared for is invasives. So what exactly is an invasive? An invasive must meet three criteria. First, it must be an introduced plant, an alien, something that’s not from around here. Not only can an invasive come from a foreign country, but from another state or even another region of our own state. An introduced plant is one that is not native and has been relocated in some way, usually by man. A large percentage of introduced plants are well behaved, fit nicely in our landscapes, and bring great joy to many people, but some are invasive. Second, an invasive must be aggressive, a bully. It out-competes the natives; it tends to take over. Third, to be an invasive it must cause harm—to people, to wildlife including native plants, or to our pocketbooks (economic damage).

Many birds, butterflies, and other wildlife depend on insects that feed only on certain native plants. In a sense, natives act as sacrificial plants to sustain the food chain.

Many invasives are not sacrificial and offer very little to the food chain or act as a block to it. Usually what sets them apart is that they aggressively take over areas. Remember, to be an ‘invasive’ it must cause harm. Economic harm is one type, and harm to native species is another type. Invasives out-compete our native plants. They tend to form monocultures that decrease plant diversity. What happens to our native plants when they are overrun by kudzu or Japanese honeysuckle or English ivy? They disappear. What happens to the wildlife that depends on the food produced by the native plants? The result is a reduction in native plants and a reduction in the native wildlife population.

Unlike fire ants, invasive plants are not an obvious problem because they don’t attack or sting people, so we often ignore its other deleterious effects. Consider kudzu: an introduction that spreads incredibly fast, causes economic damage, and crowds out natives in areas where it grows. It is creeping into the warmer, wetter regions of Texas. Beyond that species, what else is there? In Southwest Texas, salt cedar was introduced to control erosion. It soon spread to areas along rivers such as the Pecos, and because of its incredible ability to suck up water actually dried up the river itself. Years of expensive eradication measures have been successful in restoring some of the flow to the Pecos, but the river sustained a great deal of permanent damage.

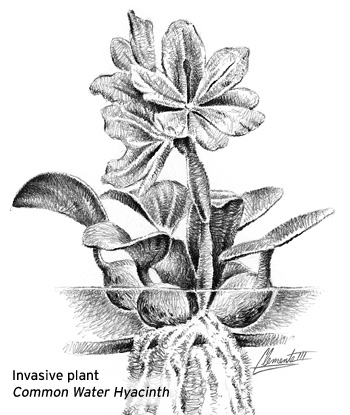

Hundreds of other plants were imported to feed cattle, control erosion, and to fulfill dozens of other worthy needs. Most of them proved harmless, but a few turned into invasives when introduced into Texas. Giant reed (arundo donax) was brought in by the highway department to control erosion in ditches along highways. Today, large clumps exist along roads in the eastern half of Texas looking like twenty-foot tall corn with a plume on top. In some areas, giant reed runs along the road for a mile or more. Aquarium or pond plants like hydrilla, giant salvinia, and common water hyacinth were dumped in storm sewers and streams or carried by a boat coming from an infested lake and now clog Texas lakes, inhibiting recreational use and fishing. Many introductions did not even prove useful for the intended purpose, yet Texas is stuck with them forever. Plants like bahiagrass, johhsongrass, and King Ranch bluestem come to mind. Others like costal Bermuda, while very useful for cattle, escaped and spread everywhere forming monocultures that displaced the bluestems, switch grass, and other natives. Its turf grass cousin Bermudagrass grew right out of your yard and displaced native plants along roadways.

Many invasives, in fact, are very attractive to look at and are highly prized in our landscapes by well-meaning, uninformed people or by people who are informed yet could care less what damage they cause. Invasives may actually be easier to grow than some natives for the very reason they are invasive; they don’t have any natural enemies in the area. That’s why ornamental invasives are used—plants like Japanese honeysuckle, nandina, mimosa tree, Chinese privet, golden bamboo, Chinese tallow tree, chinaberry, Chinese wisteria, and English ivy. They began as easy-to-grow yard plants but soon escaped to the woods and became a serious problem forming monocultures, displacing natives, and reducing diversity.

Why should we care? Harm, that’s why: the effect on native wildlife that depend on native plants for food; the economic damage to crops, lakes, rivers and streams; the ecological damage (salt cedar). It’s funny how things work out. Take an early settler in Texas who came from another country and acquired alien cattle to feed himself. Then he finds that native grasses soon disappear when heavily grazed by alien cattle (our native buffalo knew how to co-exist in harmony with native vegetation) so he imported grasses from all over the world to feed the alien cattle. From there, it spiraled out of control.

What can we do?

Don’t plant invasives. Don’t spread seeds of invasives. Inspect you clothes and shoes for seeds when leaving an area containing invasives. Power-wash your boat anytime you enter another lake. Check the state invasives list (see below) before you buy plants. Tell your nursery that they are selling invasives and should stop the practice. Eradicate invasives where possible or closely watch them if you just can’t part with them. Plant natives and support wildlife. Perhaps you can offset the harm caused by your neighbor who insists on planting invasives "because they do so well."

Become trained as a citizen scientist in the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center’s "Invaders of Texas" program and report sightings of invasives along roadsides, in parks, and on your own property.

Get educated about the impact of invasives and the benefits of using native plants. Read Matt White’s Prairie Time, a Blackland Portrait if you live near the blackland prairie or post oak savanna areas. Read Sally Wasowski’s Requiem for a Lawnmower, especially if you live in the city or have a lawn. Read Jeffrey Greene’s Water from Stone if you are interested in the Texas Hill Country. Though a little more technical, try a new book titled Rare Plants of Texas: A Field Guide by Poole, Carr, Price and Singhurst. Learn how to use Texas native plants in your landscape by reading books on the subject by Wasowski and others. Visit the "Invaders of Texas" website: www.texasinvases.org. to find information on the citizen scientist program and for invasive plant lists and other good information on invasives. Join the Native Plant Society of Texas www.npsot.org to learn more about native plants. Become a Texas Master Naturalist http://masternaturalist.tamu.edu/ to learn more about all things natural and how making any change to the environment causes something else to change. Read the spring 2006 issue of this publication for a short list of plants that make good substitutes for invasive plants and more information on using invasive plants in the garden.

Clyde McKinney is retired from commercial real estate in the Metroplex and now resides at Lake Lydia near Quitman. He is a Texas Master Naturalist, a Texas Master Gardener, a member of the Tyler Chapter of The Native Plant Society of Texas and the Tyler Audubon Society, and a citizen scientist with the Invaders of Texas program.

The Back Porch

The Back Porch

Historical and Current Assessment of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department's Private Lands Assistance Program

By Linda Campbell

Since the 1930’s Texas Parks and Wildlife Department biologists have provided habitat management assistance to landowners. In the early years, work consisted of collecting data for hunting/fishing regulations, trapping and transporting wildlife, population studies, wildlife research, and vegetation surveys.

Between 1950 and 1973, the increasing economic value of hunting lead to increasing requests for landowner assistance. Requests for assistance began on large ranches in south Texas. As it became more difficult to make a living from livestock alone, landowners sought to diversify income by selling hunting opportunities.

More landowners began to ask for advice on improving wildlife resources on their land. White-tailed deer and quality game management became the driving force in landowner requests for assistance. As requests for assistance increased in south and west Texas, field biologists saw their workload changing in response to requests for landowner assistance separate from their traditional regulatory duties. They began to document these requests and eventually shared these changes in workload with leaders in Austin.

In 1973, in response to this changing role, Robert Kemp, Director of Wildlife and Fisheries proposed to implement a private landowner assistance program. Five technical guidance biologist positions were created and a proposal to implement a technical guidance program designed to provide landowner assistance was presented to the TPWD Commission. The Commission approved the program in 1973. Under the leadership of the first five technical guidance biologists, private lands managed according to a wildlife management plan developed with TPWD assistance averaged about 1.5 million acres during the period 1973 through 1988.

The first technical guidance biologists were experienced field people with strong ties to their communities and solid relationships with the landowners they assisted. They were recognized as big supporters of the technical guidance program and showed a strong belief in one-on-one assistance to landowners. They became the model for self motivated employees focused on getting people interested in wildlife management. Each developed a unique style of working with landowners to "sell" quality habitat management by addressing the landowner’s primary interests, in most cases, game management.

During the period 1988 through 1991, five additional technical guidance biologists were hired. In 1992, Wildlife Division managers made the decision to assign the responsibility of providing assistance to landowners to all field biologists as part of their jobs. The acreage managed under written wildlife management plans and recommendations more than doubled from 1992 to1994 (2.5 to over 5 million).

The importance of working with private landowners to accomplish the agency’s mission of wildlife conservation was clearly recognized with the creation of the Private Lands Advisory Board (PLAB) in 1993. The PLAB was created to advise the Department and Commission on matters of importance to private landowners. Consisting of private landowners appointed by the Chairman of the Commission, it serves as a sounding board for private lands issues of concern to TPWD. Members are asked to examine issues and prepare responses on specific charges given to them by the Commission Chairman.

The mid-1990’s was a particularly challenging period for wildlife conservation in Texas, particularly with regard to endangered species issues. Many landowners expressed mistrust of the government in general and lack of support for rare species conservation in particular. A new approach to private lands conservation was needed. Discussion began to center around the concept of providing incentives for private landowners to manage habitat benefiting rare species, and removing disincentives inherent in the laws and policies of that time.

In 1997, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department piloted the first Landowner Incentive Program with financial support from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). The program was designed to reverse the top down regulatory approach to rare species conservation and replace it with a voluntary program that provides financial and technical assistance to landowners to help achieve their overall conservation goals for the land, including habitat-based work benefiting rare species. For many landowners, this voluntary, incentive-based approach was all that was needed to encourage participation in the conservation of rare species on their land. In 2002, LIP became a national program administered by the USFWS.

As a result of the endangered species controversies of the mid-1990’s, Section 12.0251 was added to the Parks and Wildlife Code in 1995. This statute mandated that information and species data used to develop a wildlife management plan for private landowners was confidential and could not be released without the written permission of the landowner. It provided the assurance many landowners needed to feel comfortable requesting technical assistance and inviting Texas Parks and Wildlife biologists on their land.

Another key law (H.B. 1358), passed in 1995 implemented a constitutional change by amending the Texas Tax Code to allow wildlife management as an agricultural use that qualifies the land for agricultural appraisal. Commonly referred to as the Open Space Tax Valuation for Wildlife Management, this law allowed landowners to declare wildlife management as their primary agricultural use, providing added flexibility for land managers throughout the state. The result was an increase in landowners managing primarily for wildlife and an accompanying increase in landowner requests for assistance.

As approaches to private lands conservation changed from regulatory to incentive-based, the Private Lands Advisory Board led the way in creation of the Lone Star Land Steward Awards program in 1996. This program, now in its 13th year, recognizes landowners in each of the 10 ecoregions and one overall statewide steward that have shown accomplishment and commitment to excellent resource management and stewardship on their lands. They are held up as models and the awards program itself serves as a venue for TPWD to highlight the important role private landowners’ play in conserving the wildlife resources of Texas.

Consistent with the Department’s incentive-based approach to private lands conservation, the Managed Lands Deer Program was implemented in 1999. Landowner’s participating in this program are afforded maximum harvest flexibility in exchange for providing harvest records and accomplishing management actions identified in their wildlife management plan. This has been a highly successful program and has greatly increased demand for private lands assistance.

Land fragmentation due to increasing numbers of small acreage properties continues to tax the ability of TPWD biologists to keep pace with small acreage landowners seeking assistance. Biologists throughout the state work to promote the formation of landowner associations, providing an opportunity to address wildlife conservation on a landscape scale while also providing staff an efficient way to deliver conservation information and services.

By the year 2000, TPWD reported 8.3 million acres being managed under a wildlife management plan developed with TPWD assistance. In this year, the Legislature authorized funding for 10 additional field positions to be used to provide landowner assistance. The Wildlife Division’s decision to assign landowner assistance as part of the job duties for each field biologist grew the workforce available to meet the demand. From August 2000 through November 2008, the number of active wildlife management plans and the acres managed increased from 2,272 plans and 8.3 million acres to 5,785 plans and 21.5 million acres. Wildlife association managed acreage increased from 979,597 acres in 1999 to 2.6 million currently.

It is clear that efforts to reach out to private land managers have paid off in the numbers of landowners now actively managing for sustainable wildlife populations. As we look to the future, the one-on-one, incentive-based approach to private lands assistance is becoming increasingly more difficult to sustain within the constraints of current funding and staff allocations. As one Private Lands Advisory Board member put it, "the program is a victim of its own success". Field biologists are challenged to meet the growing demand for services from new landowners buying land primarily for recreation while also providing adequate assistance to current cooperators implementing habitat improvements. They continue to devise innovative ways of working more effectively with groups of landowners while providing follow up assistance to those most interested in accomplishing habitat improvement. The accomplishments of dedicated field staff cannot be overemphasized. Most will continue to work hard to educate, enlighten, and "sell" wildlife habitat conservation to landowners because they are wildlife professionals and the message is important to them personally. TPWD will continue to seek ways to support current staff with adequate salaries, vehicles, and equipment while adding to their ranks as we strive to meet the growing demand for landowner services. In a state that is 96 percent privately owned or managed, our work with private landowners is our only hope to conserve the habitats and wildlife resources of Texas.

Linda is Program Director of Private Lands and Public Hunting for Texas Parks and Wildlife Department working in Austin.

Did You Know?

American Beautyberry (Callicarpa americana)

Also called French mulberry, American beautyberry is a 4-5 ft. tall deciduous shrub with elliptical medium green leaves. Pale pink flowers bloom in summer, with bright purple berries produced in late summer through fall. Beautyberry prefers some shade, usually growing as an understory shrub in moist thickets. The showy purple berries are often used in flower arrangements, as well as eaten by quail, mockingbird, catbird, robin, thrashers, cardinal, flycatchers, chickadees, warblers, and several mammals. Each berry contains four small seeds.

Did You Know…

- The bright purple berries of American beautyberry are eagerly eaten by many bird and mammal species, including cardinals, chickadees, warblers, mockingbirds, and quail. The berries are also edible for humans.

- The USDA is currently studying the leaves of American beautyberry as an exciting potential new insect repellent. Three chemicals in the leaves were found to repel mosquitoes, ants, ticks, and flies. This plant came to the attention of researchers because of early uses told to a grandson by his grandfather.

- The purple berries encircle the branch, forming a ball shape. The berry clusters may remain on the branches well after the leaves have dropped in the fall.

Wax Myrtle (Morella cerifera)

Wax myrtle is an aromatic evergreen fast-growing shrub, also called bayberry. There are 2 forms: Southern wax myrtle and Dwarf wax myrtle, both of which grow as understory shrub in woods, usually along streams. Wax myrtle’s crisp green leaves are coated on both sides with aromatic resinous spots. Small inconspicuous waxy berries, produced in fall and winter are eaten by at least 32 bird species and several mammal species. The waxy coating of the berries has been used since colonial times in making candles and in scenting soaps. Early colonists extracted the wax from the berries by dipping them in boiling water. Tea made from the root bark was good for relieving stomach disorders, ulcers, jaundice. For dry, itchy skin, myrtle tea was thought to be particularly soothing. Male and female flowers are borne on separate plants from March to April. Root nodules containing Actinomycetes fix nitrogen and return it to the soil, improving the soil around the plant. Wax myrtle can also colonize by suckering, a useful trait for erosion control. It can handle some salinity.

Did You Know…

- The aromatic evergreen shrub, wax myrtle, creates a delightfully hardy hedge, while also serving as shelter for many birds.

- The wax myrtle’s waxy berries were once a source of wax and bayberry candle scent. Those berries are eaten by more than 32 different bird and several small mammal species.

- Nodules on the wax myrtle’s roots contain actinomycetes, a bacteria that forms a beneficial symbiotic relationship with the plant. The plant provides carbon to feed the bacteria, while the bacteria converts nitrogen from air into a form the plant can use to grow. This process also enriches the soil surrounding the plant.

Rusty Blackhaw Viburnum (Viburnum rufidulum)

Often found along streams in wooded areas of eastern and central Texas, rusty blackhaw viburnum is a favorite among wildlife and people. Reaching 10-20 feet tall in dappled shade to full sun, the deciduous glossy, dark green leaves turn scarlet, maroon, or gold in fall. The viburnum produces bright white flower clusters in Mar-Apr., then blue-black berries in late summer to early fall. The flowers are a favored nectar source for butterflies and insects. The fruit is an important fall and winter food source for many bird and mammal species, and is edible by humans. In fact, the fruit was often used in medicines by early American folk healers and doctors to prevent miscarriages, lessen pain after childbirth, and ease menstrual cramps. The strong, straight branches of a relative, arrowwood viburnum, was the local source for arrow shafts by Native Americans.

Did You Know…

- The rusty blackhaw viburnum serves many functions in a landscape, including bright white clusters of nectar-rich flowers in the spring as nectar sources for butterflies and other insects. Once the flowers have been pollinated, blue-black berries grow in late summer and early fall and are eagerly eaten by many bird and mammal species.

- The viburnum’s glossy dark green leaves turn scarlet, maroon, or gold before they drop, creating quite a show in the fall.

- The strong, straight branches of a relative, arrowwood viburnum, were used as a source for arrow shafts by Native Americans in Texas.

Candelilla (Euphorbia antisyphilitica)

Candelilla (Spanish for "little candle") is a rare succulent shrub of the Chihuahuan Desert. It is one of many native species of Euphorbia commonly known as "spurge." Did you know that the plant is leafless and photosynthesizes through the stems?

The most remarkable feature of this plant is its wax content. The plant forms clusters of thin (about 1 cm), straight, wax-covered stems on gravelly flats and rocky ledges.

Did You Know…

- The wax on the outside of shoots is an adaptation to prevent desiccation in the arid climate.

- Candelilla only grows from the Big Bend area of Texas south into many of the states of Mexico including Nuevo Leon, Coahuila, Hildago, and Chihuhua. It grows on limestone ledges above the banks of the Rio Grande at Big Bend National Park and at the TPWD Black Gap Wildlife Management Area.

- Except for range grasses, Candelilla was once the most commonly used plant of the Big Bend area of the Chihuahuan Desert.

- Candelilla has served for a lengthy time as a raw material for candles, soaps, various polishes, chewing gum, and general lubricants including use in insulation. Frontier harvest of camellia and other plants, although primitive, was successful in widespread extirpation of the species. The species is still rare in areas where it was once abundant prior to commercial harvest.

- Medicinal properties have long been recognized in Candelilla. The species name "antisyphilitica" refers to the erroneous folk belief in Mexico that the plant can be used for treatment of venereal disease. It is noteworthy that scientific names are not always based on actual scientific facts.

Apache Plume (Fallugia paradoxa )

Apache Plume was named for its feathery seed heads, which appear amazing similarity to Indian feather bonnets. It occurs over much of the southwestern U.S. and into northern Mexico, at elevations from 3000 to 8000 feet. Apache Plume is a xeric shrub of dry desert arroyos and foothills in limestone, sands, loams, clay and well-drained soils. Chihuahuan desert is generally lacking in trees.

Reports of its value as food to wildlife vary, but most sources rate it as fair or moderate. Apache plume offers seeds, high in energy for wildlife. The flowers provide nectar for insects, including bees and butterflies. Apache-plume leaves, stems, and fruit may be important to mule deer during an average growing season in the desert foothills. During poor growing seasons in the Trans-Pecos browse use is higher.

Apache Plume blooms in April and May with small white rose-like flowers, followed by white to pink feathery fruit clusters from May to October. These small fluffy plumes are produced in great abundance and provide a dramatic effect when backlit by the sun. Apache Plume is not only good for wildlife but its conspicuous flowers, decorative, plume-like seeds and drought tolerance make it a popular ornamental plant in landscapes.

Did You Know…

- Apache-plume provides good cover for small mammals and ground-dwelling birds, such as Gambel’s and scaled quail. Birds use the fluffy achenes (seeds) for nesting material and cover.

- Many birds nest in Apache plume include mourning dove, roadrunner, black-chinned hummingbird, ladder-backed woodpecker, ash-throated flycatcher, cactus wren, mockingbird, crissal thrasher, brown-headed cowbird, pyrrhuloxia, blue grosbeak, varied bunting, and house finch.

- In higher elevations, Apache-plume is an especially important browse plant for Mule Deer during the winter.

- Apache Plume is crucial for rehabilitation of disturbed sites, especially under arid or semi-arid conditions. It is valuable for erosion control and soil stabilization because it spreads underground vegetatively. Apache Plume spreads naturally to roadside shoulders and barrow pits. Native Americans used bundles of twigs from Apache plume as brooms and older stems for arrow shafts. A drink made from the leaves was used as a growth stimulant for hair.

Havard Agave (Agave havardiana)

Agaves are a low growing evergreen plant with succulent leaves that form a basal rosette. The leaves have a blue-gray color and are tipped in a hard spine; the leaf margins may also have spines. Agaves bloom once in their lifetime and then die

Havard agave is found in the mountains of central Trans-Pecos and Big Bend of Texas; Chihuahua and Coahuila, Mexico, 4,000 to 6,000 ft. elevation.

Did You Know…

- There are eleven species of agave in Texas?

- Havard agave is one of a few agave species in Texas and the United States that open their flowers at night and attract bats with profuse amounts of nectar. The plant only blooms once in its life after growing 20-50 years. Mexican long-nosed bats pollinate the bright yellow flowers.

- The interdependence between Havard agave and similar agave species and nectar feeding bats is so strong that one might not be able to survive without the other. Agaves and long-nosed bats are the products of thousands of years of co-evolution and have developed special adaptations for living together. Nectar and pollen are the main food items for long-nosed bats. Their tongue and muzzle are elongated, an adaptation for feeding on nectar that accumulates inside the tubular-shaped agave flowers. In addition to consuming the nectar the bats also cross-fertilize plants when foraging on pollen is picked up inadvertently on their fur. The rewards are mutually beneficial for both the plant and the bat

- Tequila is obtained from agave or century plants that are mainly pollinated by bats. Tequila is created through the distillation of agave juices. Next time you are enjoying a margarita, stop to reflect on the contribution made to the tequila industry by long-nosed bats. The decline in populations of long-nosed bats could have horrific consequences. Agave plants are important components of desert communities, providing food and cover for a diversity of wildlife species.

- Bees, moths, lizards, hummingbirds, woodpeckers, orioles, finches, sparrows and field mice all depend on plants pollinated by long-nosed bats, and that a decrease in agave or bat populations would have a detrimental affect on their survival. Only recently has man realized that bats are partners in the association of certain agave species, like Havard agave. Long-nosed bats are endangered by modern man's activities. Disturbing the fragile links that connect agaves, long-nosed bats, and the diverse assemblage of animals that find food or cover on these plants will impact the ecosystem in which they occur.

Hackberry, Sugarberry (Celtis laevigata)

This tree is often considered by many to be a "trash tree" and is therefore not valued in many cities.

Did You Know…

- This tree is a major provider of food for wildlife Many animals feed on the fruit. These include bluebirds, robins, cardinals, mockingbirds, cedar waxwings, thrashers, white winged doves, golden fronted woodpeckers, hognosed and striped skunks, ring tailed cats and opossums.

- Additionally, this tree is the larval host plant for the Question Mark, Mourning Cloak, Pale Emperor, Snout and Hackberry butterflies.

Post Oak (Quercus stellata)

In nature, this species is a tough, hardy tree that forms the backbone of the Cross Timbers ecological zone.

Did You Know…

- Post Oak trees are extremely sensitive to root disturbance. Many disappointed homeowners have built their home amidst their beautiful Post Oaks only to watch them die within a few years after home construction.

- Post Oaks can't tolerate "fill" (soil that's brought in to raise the ground level) being placed on the roots, nor do they like to be irrigated. Sadly, many homeowners have unknowingly killed the very trees they love by installing irrigated lawns beneath them.

Mistletoe, Hairy Mistletoe (Phoradendron tomentosum)

This plant is often despised for the damage it does to its host tree.

Did You Know…

- A fascinating species, Hairy Mistletoe is both autotrophic (feeds itself via photosynthesis) and semi-parasitic (feeds off of the host tree).

- Mistletoe has the capacity to make its own food from the sun's energy, but it also "steals" water and nutrients from the host tree. This thievery is why the genus is called Phoradendron. In Greek, "Phor" means "thief" and "dendron" means "tree," so the genus name loosely translates as "tree thief."

- Mistletoe is poisonous to humans. All parts of the plant contain toxic chemicals, but the berries are especially toxic.

- Mistletoe isn't all bad, though. Several species of birds (including cedar waxwings and bluebirds) are able to process the toxins and actually enjoy eating the berries. White-tailed deer are known to eat the foliage as well.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, TX 78744

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, TX 78744