Spring 2009 A publication of the Wildlife Division—Getting Texans Involved

Brush

The extreme southern tip of our great state is a tangle of brush and thorn that is often unappreciated. Lacking in artistic splendor or decorative allure, this area is rich in diversity and unique in biodiversity.

Ourauthors this month cover a broad spectrum as they explore the challenges facing the South Texas Brushlands. Matt Wagner closes the chapter with a look at water – probably the greatest challenge facing land managers in this land of drought and flood.

Enjoy our trip through the brushlands, where beauty truly is in the eye of the beholder!

Challenges

and change in the thornscrub

By Josh Rose

Brushlands. Thornscrub. Not charismatic or exotic-sounding names. Not anything that likely to send people running to call their travel agents. For birders and nature enthusiasts though, the South Texas Brushlands ecoregion does exactly that. Ecotourism brings millions of dollars per year into south Texas, and for some towns constitutes a significant factor in the local economy. Ironically, the section of the brushlands where ecotourists spend most of their time and money has lost a massive portion of its wildlife habitat to agriculture and development, and most of the little remaining habitat is critically threatened by man-made environmental challenges. As the tide of tourist dollars has made local communities aware of the value of the remaining fragments, government agencies and landowners have begun protecting and managing the last of the area’s native habitat, and even reversing the tide and expanding habitat through rehabilitation of once-cleared land.

Green Jay

Two qualities make the brushlands of south Texas a magnet for bird and nature lovers. The first is biodiversity. Just the four southernmost counties, known collectively as the Lower Rio Grande Valley (LRGV for short), have had over 500 bird species documented within their borders, more than 46 entire states of the US! Butterfly diversity, over 300 species, is similarly beyond any other area of the country. Throw in dragonflies, damselflies, mammals, reptiles, plants, and all the rest, and even longtime residents never run out of new creatures to discover.

The other quality that attracts so many ecotourists to this area is the proximity to the tropics. Many species of the region are unknown further north, and a number of these are brilliantly colored, or have interesting behavior, or are otherwise strikingly new and different to the vast majority of visitors. The neon hues of the Green Jay and Altamira Oriole; the unmistakable noises of the Plain Chachalaca and the Great Kiskadee; the peculiar lifestyles of the Hook-billed Kite and the Northern Beardless-Tyrannulet; and that’s just the birds! Throw in transparent-winged butterflies, honey-making paper wasps, the critically endangered Speckled Racer, the formerly extinct in the US Aplomado Falcon, 8-foot-long rattlesnake-eating Texas Indigo Snakes, the bizarre Mexican Burrowing Toad, the last few surviving Ocelots in the country, and many other possibilities, and the lure of the brushlands becomes all but irresistible.

Great Kiskadee

The human communities of the brushlands have taken to enhancing their appeal to travelling nature lovers by sponsoring a variety of annual nature festivals. Harlingen’s Rio Grande Valley Birding Festival is entering its 16th year of existence. Newer birding fests have arisen in Brownsville, McAllen, and Laredo, while other yearly Valley festivals focus explicitly on butterflies or dragonflies. Further north in the brushlands, Kingsville and Three Rivers have gotten into the nature festival business as well.

The LRGV has the greatest biodiversity and highest concentration of subtropical species within the brushlands region. However, the rich floodplain soils and warm climate of the area made it an irresistible location for agriculture as well. Citrus, sugar, cotton, onions, and many other crops became big business in the Valley, while cattle ranches claimed most of the brushlands further north. The climate is the lure for a massive and rapidly growing population, and the proximity to Mexico has become the engine for a booming economic expansion. Farmland and other development has claimed most of the Valley’s land area. By some estimates, as much as 97% of the original habitat here is gone.

The area is threatened by more subtle forces as well. Non-native plant species, especially the pernicious duo of Guinea Grass and Buffel Grass, are overwhelming native ecosystems, crowding out wildflowers and native grasses, interfering with establishment of young trees and shrubs, and greatly increasing the risk of. The disturbance more natural to this area is flooding, especially the forests along the Rio Grande; but dams and water diversions have all but eradicated flooding from the Valley, leaving the highly diverse floodplain forests dying for a drink.

Recognizing that the remaining wildlife habitat is valuable, local communities are taking steps to combat the threats to the brushlands. The first step is to protect the remaining habitat. The largest step in this direction was made by the federal government’s US Fish & Wildlife Service, which created the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge. The LRGV NWR includes dozens of tracts of land, many thousands of acres, scattered across all four of the Valley counties. The state of Texas has protected thousands of additional acres of brushland in the scattered units of the Las Palomas Wildlife Management Area. Fragments of critical habitat are in the hands of city and county governments, national nonprofits like The Nature Conservancy and the National Audubon Society, or independent local groups including the Valley Land Fund and Frontera Audubon.

Plain Chachalaca

As the remaining habitat has gained protection, agencies are working to reverse the trend of habitat destruction by creating new habitat in areas that had been cleared and developed. The World Birding Center is re-establishing brushland, forest, and wetlands on sites that had formerly been a Harlingen landfill, an Edinburg sewage treatment plant, and agricultural fields in Weslaco and Mission. The Rio Reforestation workdays and The Native Plant Project bring native plants to nature preserves, birding hot-spots, and private homeowners alike. Smaller tracts have had great success locally, eliminating Guinea Grass and re-establishing native vegetation communities, while landowners and agencies tinker with remedies for more extensive lands. Private landowners, now intrigued by the potential profits of ecotourism, have taken active interests in improving the habitat quality of their lands and opening their properties to wildlife watchers.

Flood deprivation may be the most challenging problem facing the LRGV. Chronic drought and upstream diversions reduce the water supply reaching the lower Valley. Demand from residential and agricultural use boosts prices and strains the budget of wildlife habitat managers. Even so, the past decade has seen long-dry areas immersed at a number of national wildlife refuge and state park tracts in deep south Texas.

After a century of being depleted and degraded, the 21st century sees the South Texas Brushlands taking its first steps in the other direction. Some of the most spectacular wildlife attractions in the region are sites which were all but devoid of wildlife a decade ago. Stiff challenges remain, the most recent being the border fence, but there is plenty of reason to look forward to the brushlands of the future.

Josh is a Natural Resource Specialist at Bentsen Rio Grande Valley State Park of the World Birding Center in Mission, Texas.

Wildcats

and the South Texas brushland

By Michael Tewes

It’s twilight. The bobcat sits in a frozen crouch, its back arched and body coiled like a tight spring, eyes and ears focused forward. It is watching silently, waiting for the rabbit to make a mistake.

Ocelot

Poor evening light, and lack of surrounding movement, assures the rabbit that it can venture into the open for a short distance to taste the grassy morsel just out of reach. That’s a fatal mistake. The feline coil is released into a short but intense burst. Pouncing with its forepaws, the bobcat pins its dinner, and quickly applies its canines to the rabbit’s neck. Rabbit is served for dinner.

This isn’t a graphic nature film - just an action occurring hundreds of times daily in Texas by one of nature’s most efficient predators - wildcats. If you spend time in the outdoors, you may be lucky enough to see this predator in action, particularly in the South Texas Brushlands. South Texas has some of the highest densities of bobcats in the United States. The abundance of their primary prey, cottontail rabbits and cotton rats, makes this region a cornucopia for bobcats.

Other groups of wildlife have high diversity in the South Texas Brushlands including amphibians, reptiles and birds. Shrubs are decorated with feathered jewels like the green jay, kiskadee, painted bunting, vermillion flycatcher, and many other birds found in this border region adjacent to Mexico. This bird diversity makes the area a prime destination for American birdwatchers. It seems diversity begets diversity.

This diversity is reflected in the wildcats. South Texas is home to more different kinds of wildcats than any other place in the United States. The region provides habitat for mountain lion, bobcat, ocelot and possibly the jaguarundi. Historically, jaguar also roamed southern Texas and there was one report of a margay on the border during the 1850s.

Mountain Lion

As professor with the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute at Texas A&M University-Kingsville, I have been fortunate to supervise a cadre of highly-skilled graduate students who have spent the past 25 years unlocking the ecological mysteries of these wildcats. And many of these projects have been funded by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) including studies on ocelot ecology and detection with remote cameras, mountain lion ecology in southern Texas, mountain lion genetic variation and bobcat harvest studies. Currently, TPWD mammalogist, John Young, has been lead on another project developing a model of mountain lion habitat and distribution.

Of Texas’ cats, the mountain lion is the largest, usually weighing over 100 pounds. This size helps it take down their primary prey - white-tailed deer. In contrast, the smallest cat in Texas, jaguarundi, weighs about 10 pounds or the size of a large house cat. Many of the jaguarundi sightings from around Texas are actually black house cats looking for food along roadsides or in pastures. The last photograph of a jaguarundi occurred near Brownsville during 1986, and they were never documented north of the Rio Grande Valley, even during the 1800s or 1900s.

The bobcat and ocelot are medium-sized cats that weigh about 20 to 25 pounds. Bobcats are common over most of Texas, being habitat generalists that will use almost any environment. In contrast, ocelot are rare with a population less than 100 individuals in southern Texas. This represents its only occurrence in the United States. Ocelots are habitat specialist that use extremely dense thornshrub cover, so dense that people have major problems trying to move through it. Less than 1% of South Texas has this brush. Consequently, the ocelot is listed as endangered because of its rarity and its scarce habitat.

Having been raised in South Texas with a life-long interest in wildlife, I have been fortunate to experience this great diversity in our native wildlife. And the varieties of wildcats are icing on the cake.

Mike is a professor at Texas A&M University Kingsville conducting research on cats of south Texas.

Technical guidance in

South Texas

By Alan Cain

South Texas is one of the most biologically diverse regions in the United States, home to over 1,100 plant species and 700 vertebrate species. Rich in a history of large sprawling cattle ranches such as the King, Kenedy, Piloncillo, East and many others, South Texas has been somewhat insulated from the numerous issues confronting wildlife and wildlife habitats. In fact, a recent publication from the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute about the importance of South Texas to wildlife conservation is appropriately titled the "The Last Great Habitat" - a very befitting moniker for this region.

South Texas boasts a world-class deer population, one of the last strongholds for bobwhite quail, a variety of rare species including the endangered ocelot, premier bird diversity drawing birders from across the globe, and diverse landscapes from coastal prairies to the thornshrub woodlands of the Rio Grande Plains. This unique ecological area would not be nearly as pristine as it is today were it not for the private landowners and their strong desire to maintain the integrity of the diverse ecosystems in South Texas. Since most of Texas is privately owned, 97% by some accounts, private landowners are the key to sustaining the variety of plant, animal, and bird life in this region.

As our state demographics change from a rural background to one of more urban or suburban composition, people become increasingly less intimate with the processes of the natural world and how to sustain these important natural plant and animal communities. Recently, South Texas has also experienced a shift from traditional cattle ranching to landowners buying property solely for hunting and outdoor recreation. Even traditional livestock operations have realized the value of wildlife related activities, and are incorporating these ventures into their business plans to maintain a financially stable ranch. With this shift in the value of wildlife and the native habitats it has become critical for both landowners and non-landowners to have the opportunity to seek professional unbiased guidance and information on management of our natural resources.

The TPWD technical guidance program has been instrumental in promoting wildlife and habitat conservation across Texas. The team of biologist in the South Texas wildlife district exemplifies what the technical guidance program can accomplish. Fourteen biologist covering thirty counties encompassing approximately twenty-one million acres, have brought over six million acres under management through more than twelve hundred wildlife management plans. This in addition to the other jobs they are tasked with including wildlife research, public outreach, and annual surveys of wildlife populations.

Through technical guidance, field biologists provide expertise to landowners and managers leading to management and conservation of wildlife habitat and thus the various wildlife populations that utilize that habitat. Technical assistance comes in a variety of forms, including informative publications, field days teaching landowners about various habitat management techniques, to more detailed one on one visit to a landowner’s property resulting in a wildlife and habitat management plan. The benefits are reduced or stopped habitat fragmentation, habitat loss, urban sprawl, other critical issue affecting wildlife and wildlife habitat, and helping landowners to improve quality and quantity of native habitats and wildlife. Habitat is the cornerstone to wildlife management and without habitat we will not have wildlife and natural resources to enjoy. As technical guidance biologist, Jimmy Rutledge, stated "The days I’m in the field is where I feel I’m making a difference for the wildlife and the people of the State of Texas". Citizens of Texas all benefit from technical guidance whether we own a piece of land or not. Sound wildlife and habitat management practices translate into more than just sustaining healthy habitats and wildlife populations. Water conservation ensures our rivers, streams, and aquifers provide clean water. Land conservation enhances our ability to produce our food and to provides places where we can get away a enjoy the peaceful outdoors.

Without private landowners wildlife conservation would be a difficult task. Rene Barrientos, a South Texas rancher, is a classic example of the benefits of the technical guidance program. Rene purchased an 8,000 acre "worn out" old ranch in La Salle County in 1995. It had been severely overgrazed & root plowed, and had very little water other than a section of the Nueces River - not very good conditions for wildlife. Not unlike many landowners in South Texas, Rene was concerned with the quality of his deer herd as well as improving over all habitat conditions. Barrientos contacted technical guidance biologist, Jimmy Rutledge, about the technical guidance program and what could be done to improve the wildlife conditions. Rutledge and Barrientos began formulating a wildlife management plan and defining specific goals to be accomplished to improve habitat and wildlife conditions on the ranch. Barrientos took some convincing on how exactly that would best be accomplished. "When he first contacted me" Rutledge says, "it’s fair to say that he didn’t think much of my ideas. We laugh about it now, but that first phone call he was somewhat skeptical."

Using prescribed burning, rotational grazing and cross fencing, disking, deer harvest, water improvements, and a host of other habitat management tools Barrientos has transformed that old "worn out" ranch into a paradise for wildlife. Over 150 bird species have been documented on the ranch, Texas horned lizards are not a rare sight, and healthy shrubs and native grasses such as guayacan and Arizona Cottontop are common. As for the quality of the deer herd, the proof is in the harvest. With an initial goal in the management plan of being able to harvest 6 bucks scoring over 160 B&C, the ranch has far surpassed that goal with over 16 bucks exceeding that magical 160 B&C mark this year.

Mr. Barrientos received the Texas Parks and Wildlife Lone Star Land Steward Award in 2004. The Lone Star Land Steward Awards program recognizes and honors private landowners for their accomplishments in habitat management and wildlife conservation. The program is designed to educate landowners and the public and to encourage participation in habitat conservation.

"I think recognition of the ranch, not necessarily the individual, bears testament to Parks and Wildlife, especially their technical guidance program, which assists landowners," said Barrientos. "It’s not Parks and Wildlife that sets the goals, but they work with the landowners to set objectives in designing a plan that’s not species-specific, but it helps everything in improving the habitat."

Contact your local biologist if you are seeking technical assistance or would like to know how you can manage, improve, and maintain the wildlife and native habitats on your property. You can find your local biologist by following this link on the TPWD webpage, http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/landwater/land/technical_guidance/biologists/ .

Alan is District Leader for the Wildlife Division in south Texas.

A New Jewel

Among Texas State Parks

By Katherine Miller

Olive Sparrow

Just northwest of Brownsville’s city center lies a new state park, Resaca de la Palma. Acquired by Texas Parks and Wildlife in the 1970s, the land has a diverse history. The periodic flooding of the Rio Grande created resacas, or ox-bow lakes, that curved through south Texas brushlands. Sugar hackberry, black willow, retama, and zarza grew along the resaca while the Tamaulipan thorn-scrub remained dry and arid. Over time four main habitats developed at Resaca de la Palma State Park: sugar hackberry woodland, ebony-anacua woodland, Tamaulipan thorn-scrub, and grasslands.

All of these habitats can be found within the 1200-acre park, sustained by a fifth habitat, the resaca itself. Here at Resaca de la Palma State Park the wildlife flourish. The resaca provides a necessary home for the Rio Grande Lesser Siren, Rio Grande Chirping Frog, and various fish species. The Ringed kingfisher flies along the resaca searching for their prey. In the woodlands, warblers flit in the trees looking for caterpillars and other bugs. These caterpillars will develop into hackberry and tawny emperors, and band-celled sisters. The Tamaulipan thorn-scrub provides a dense thicket for white-eyed vireos, verdins, and other small birds and wildlife. And in the grasslands, summertime finds Groove-billed anis, olive sparrows, and other breeding birds that feed on grass and nest in the low shrubs.

As spring slowly starts in the valley, we have noticed wildflowers and trees beginning to bloom and leaf out. Huisache covers the park with fragrant orange puffballs. Both vervain and verbena dot the trails purple. In damper areas the arrowhead has small but showy white flowers. We are also watching eagerly for migration this year; the first spring that the resaca will have water since the 1970s. South Texas is in two major migratory flyways: central and Mississippi. During the spring months birders watch for fall-outs - cooler days when the birds stop in one habitat to rest before continuing north. Resaca de la Palma State Park promises to be a rich area for these fallouts that come with cold fronts.

Resaca de la Palma State Park promises to be a place of importance for birders and wildlife viewers. We also cater to the local community, offering educational programs to schools, tours for a variety of groups, and we are developing summer programs for families. The park has over 8 miles of trails and four observation decks, perfect for spending the day outside with your family, or with your dog. Resaca de la Palma State Park celebrated its Grand Opening December 6th 2008, using the theme: "A Family Day At the Park". Since our opening we have had over 2,700 visitors touring our park.

Resaca de la Palma State Park is located in Brownsville northwest of the center of town. From Expressway 77/83 take FM 1732 west to New Carmen Blvd. Turn south here and follow the road to where the gravel starts. The entrance to your park will be on your left. Resaca de la Palma is open 7 days a week from 8 am to 5 pm. For more information please visit our website at www.worldbirdingcenter.org.

Katherine is the Natural Resource Specialist at Resaca de la Palma State Park

Amphibian Watching

in South Texas

By Lee Ann Linam with excerpts from the notes of David Martin

On the surface, South Texas doesn’t seem like great place to be an amphibian-watcher. Cactus, drought and small wetlands that dry up regularly are pretty hard on animals with semi-permeable skin. In reality, South Texas is unlike anywhere else for frogs. The Lower Rio Grande Valley is home to 21 anuran (frog and toad) species, five of which are native to nowhere else in the United States. Many of these are remarkably adapted to the rigors of life in South Texas. The trick is to figure out when and where to find frogs in South Texas.

That’s where David Martin stepped in. As a Texas Amphibian Watch volunteer to David has contributed significantly to our understanding of frogs in South Texas. David, a keeper in the herpetology department at Gladys Porter Zoo in Brownsville, provided data to Texas Amphibian Watch from 2001 until his departure from the zoo in 2007. He was invaluable as an instructor for Texas Master Naturalist workshops on amphibians, but his greatest contribution may have been the insights he provided into South Texas amphibian biology based on long, long hours in the dark along the roadsides of the Valley. He gathered data on 16 anuran species and 3 salamander species. David was generous in sharing his insights and field notes with Texas Amphibian Watch. Through the excerpts below everyone can gain an appreciation for the intricacies of amphibian life histories in the Lower Rio Grande Valley and the dedication of a true field herpetologist…

Spooky Sounds, Bogged-down Trucks, and Sleepless Nights — Field Notes from a South Texas Herpetologist

David Martin

[Photos and notes are excerpts from those submitted by David Martin to Texas Amphibian Watch; occasional summaries of David’s counts are provided in italics and common names have been inserted throughout]

2001

Plains Spadefoot Toad

I made a preliminary run of my Starr County route in June. It had rained about 2 inches the previous day. This was the most significant rain even on the route all year. I heard almost nothing, only a few Great Plains Narrowmouth Toads (Gastrophryne olivacea) at one station. It demonstrated to me that in that area, intense deluges are necessary to have any significant calling in the summer. Just to the south, near Rio Grande City, it had rained about 4 inches. This was sufficient to bring out Texas Toads (Bufo speciosus) and a few Green Toads (Bufo debilis), but not much else. This Sept, normally our wettest month, was again rather dry, and we ended the year with less than 17 inches. I believe there has been virtually no amphibian breeding on my route in the last 8 months.

In Willacy County, by contrast, there were two substantial rain events this spring. In a small area of southern Willacy County, it rained 5-6 inches in March, and again in April. Both times this elicited huge choruses of Texas Toads and Couch’s Spadefoot Toads (Scaphiopus couchi). The second time there were a few Plains Spadefoot Toads (Scaphiopus bombifrons) mixed in. Yet a few miles to the north, where it rained only an inch or two on both occasions, there was no evidence of any spadefoot breeding.

All in all, I think amphibian breeding was very patchy in S Texas this year.

2002

Sheep Frog

May 2002 - This year we finally got a fairly decent rain in May, and I observed that a narrow swath of heavy rain had occurred in Willacy County and into northeastern Cameron County. Outside this swath, it had only rained 1-2 inches. But within it, 3-4 inch accumulations had occurred. The next night I went up to Willacy County. In the swath, which was only a few miles wide, there were many Texas Toads and Couch’s Spadefoot Toads calling. Outside the swath, I heard almost nothing, only a few narrowmouth toads. From about 5 miles east of Raymondville to 8 miles southeast of Raymondville, several large choruses consisting mostly of Texas Toads and Couch’s Spadefoots were heard. In at least 4 of these choruses, there were small numbers of Plains Spadefoots, and one had a few Gulf Coast Toads (Bufo valliceps).

On the Raymondville-Port Mansfield highway, within the swath, I heard, for the first time, the Sheep Frog (Hypopachus variolosus). There were some Couch’s Spadefoots calling with them, but interestingly, no Bufo. The Sheep Frogs were quite easy to see, they do not hide while calling as do narrowmouths.

I had been in this area after Hurricane Bret. It had received at least 6 inches of rain and was far more flooded then. I heard many spadefoots at that time but not Sheep Frogs. This suggests to me that Sheep Frogs are more seasonal than many other South Texas anurans.

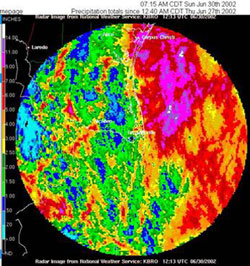

Doppler rainfall map — June 30, 2002

June 2002 - Last night’s observations reinforced for me the importance of consulting doppler precip total maps, as rain is quite patchy and frog breeding is correspondingly quite patchy on any given night. My experience is that about 4 inches of rain are necessary to bring out spadefoots and Texas Toads. At least 5 are necessary for Mexican Burrowing Toads (Rhinophrynus dorsalis). In a narrow zone it had rained 5+ inches, all of the burrowing toads were heard in this area.

July 11, 2002 - I finally got to hear Marine Toads calling, which I believe completes my list of South Texas specialties.I learned a good deal night before last (10-11 July), but at a price: Didn’t get home until 5:00! I heard seven species among eight different sites, including five sites with Mexican burrowing frogs and four with White-lipped frogs (Leptodactylus fragilis).

July 17, 2002 - It keeps insisting on raining heavily in Starr County, and I keep running up there to check on anuran breeding. Here are some results from last night’s cruise of 16-17 July. In total I heard 10 species among the eight sites I visited, including Sheep Frogs, Mexican Burrowing Toads, White-lipped Frogs, and Marine Toads. These are my first records of Sheep Frogs in Starr County. They are hard to hear at a distance amongst Texas Toads and narrowmouth toads.

Saw three Marine Toads on the road, one east of El Sauz, two in the northern part of the county.

2002 Summary: I believe it is possible that Mexican burrowing toads occur in southern Jim Hogg County, but there are no public roads in the area to make investigation possible. Burrowing toads are obviously more sparse in northern Starr County than in southern. In Cameron County there is a rather abrupt transition, going northwest, from an anuran fauna dominated by Gulf Coast Toads and Mexican Treefrogs (Smilisca baudinii) to one dominated by Texas Toads and spadefoot toads. This transition occurs near the Arroyo Colorado in the vicinity of Rio Hondo.

Mexican Burrowing Toad

Couch’s Spadefoot does penetrate deep into Cameron County, but becomes very sparse south of Los Fresnos. Neither Mexican Treefrogs nor Rio Grande Chirping Frogs (Syrrhophus cystignathoides) have yet been heard north or west of Rio Hondo. This was a remarkable year for anuran breeding in S Texas; I do not expect to see another like it soon.

Recently we had some light rain, not enough to initiate frog breeding, but I am always watchful. I have yet to hear Strecker’s Chorus Frog (Pseudacris streckeri), Dixon has it in Willacy County but not Cameron.

On to the 2003 data:

Background: With 33.71 inches, 2003 was the wettest year in Brownsville since 1984. 40% of this fell during a 13-day period of September. Northeastern Cameron County was particularly deluged.

On 19 Sept 2003, I cruised 3 areas and heard eight species. About 1 mile west of Port Mansfield I heard several Strecker’s Chorus Frogs. This was the first time I heard this anuran in S Texas.

Very heavy rains occurred in Hidalgo County in early Oct. Large areas on the outskirts of Mission were underwater. On 4 Oct 2003, I heard six species and found 4 adult and one juvenile Marine Toad on the road.

2004

This year, I have been trying to get information about local salamanders. In the process, I have found many sites with leopard frog tadpoles. It is readily apparent that Rio Grande Leopard Frogs (Rana berlandieri) prefer to breed in the winter, and have done so this winter at numerous sites in Cameron, Willacy, and Kenedy Counties. On 22 Jan 2004, I found an adult male Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) next to a pond in southwestern Kenedy County. This animal was in breeding condition.

That night I found a spadefoot metamorph in the same general area. I believe it is Hurter’s Spadefoot Toad (Scaphiopus hurteri). If so, it is the first individual of that species I have seen in south Texas. On 4 Feb 2004, I found numerous Black-spotted Newt (Notopthalmus meridionalis) larvae at a pond in Kenedy County. One individual was an albino.

This has been a very unusual spring. At present we are more than 4 inches above average. During March I heard 10 species in Cameron and Hidalgo counties.

2005

This year was not a huge amphibian year, but I did learn 3 important things:

- White-lipped Frogs more common in Starr County than I thought. It does not call most vigorously right after heavy rains. The really persistent calling seems to occur in the weeks that follow, apparently in anticipation of a second rain event.

- Black-spotted Newts apparently breed in winter, at least I found fairly small larvae in Feb.

- At least one Siren breeding event occurred late last winter or early in the spring.

2006

2005 was a very dry year in southern Texas, and I was not able to collect any appreciable field data on amphibians. 2006 was only a little better. In late June a major rain event occurred in western Hidalgo County. I investigated areas just north of Mission and heard Texas Toads and Couch’s Spadefoot Toads in full chorus at several localities. A few areas close to Mission also had Gulf Coast Toads in full chorus. I saw quite a few Marine Toads on the roads but heard none calling. Marine Toads seem to be fairly common in the citrus groves just north of Mission but I have not yet been able to find breeding sites there.

Mexican Burrowing Frog tadpole

Texas Toads were surprisingly silent, it is a common anuran in this area. One Mexican Burrowing Toad breeding site has been eliminated. It was a small impoundment and has been bulldozed. This was in fact the only site in which I have actually seen Mexican Burrowing Toad tadpoles. However, there are at least 15 other sites in Starr County at which I have heard them, including right in El Sauz near the bridge. I have also heard White-lipped Frogs in considerable numbers at El Sauz, but heard neither species there on this occasion.

On Sheep Frogs - There is one pond in Willacy county that is quite unusual in its abundance of Sheep Frogs. Usually this species occurs in small choruses mixed with larger numbers of narrowmouth toads. However, in this pond I have not heard narrowmouth toads or any other anuran except for Couch’s Spadefoots. Sheep Frogs are extremely abundant in the pond when breeding.

2007

June 24 — Willacy county - This was the first time I had ever heard Hurter’s Spadefoot Toads. I had suspected that they occurred in the deep sands of northern Willacy County and points north, and this confirmed it. What was interesting was the very sharp demarcation between Hurter’s Spadefoots and Couch’s Spadefoots, corresponding exactly to the transition from deep sands to clays. No Hurter’s were heard at any Couch’s site or vice versa.

Strecker’s Chorus Frogs were not heard on 24 Jun near Port Mansfield, in areas that I have heard them in the cooler months. This suggests that Strecker’s is one of the very few anurans in southern Texas that will not breed in the warm season, even after very heavy rains. This species seems to have a distribution similar to that of Hurter’s Spadefoots in southern Texas, restricted to the deep sands that run from the coast in Kenedy and northern Willacy Counties to eastern Jim Hogg County.

Thanks, David, for much insight into the amazing amphibians of South Texas!

Lee Ann is the coordinator of the Texas Nature Trackers program working out of Wimberley, Texas.

Hummingbirds

of the South Texas Plains

By Mark Klym

We sit quietly in the garden, content in the cool morning breeze watching the Mockingbirds and listening to Kiskadees welcome the dawn. Suddenly the sqawk of the Kiskadee is joined by a scolding chatter as the air around us hums to the sound of rapidly whirling wings. There, near the edge of the lantana bush is an emerald green glow supported on cinnamon wings barely visible in their rapid cycle.

The morning visit of a Buff-bellied Hummingbird can be enjoyed throughout the South Texas Brushland, but especially along the Lower Rio Grande Valley and in areas where shrub and brush are plentiful. Often the Buff-bellied is joined by hummingbirds more familiar to many Texans — the Ruby-throated Hummingbird and the Black-chinned Hummingbird. The plentiful brush and amazing plant diversity of the brushlands provide abundant and diverse food for these birds. As a result, one can often enjoy them feeding in natural settings as opposed to the feeders we usually see them visiting.

Winter in south Texas often brings even more hummingbird diversity. Rufous Hummingbirds can be a common visitor, especially where evergreen plants provide shelter. In recent years, some of our state parks have enjoyed the Allen’s Hummingbird. This close relative of the Rufous Hummingbird shares many characteristics of its cousin, and thus care must be exercised by birders observing these birds. The Green-breasted Mango that visited several gardens in the area provided unique viewing opportunities. Blue-throated Hummingbirds, Anna’s Hummingbirds and Lucifer Hummingbirds have also graced state parks and home gardens of South Texas.

South Texas can be a hummingbird lover’s paradise. Visiting any of the World Birding Center sites can provide the birder with plenty of hummingbird diversity.

Mark is coordinator of the Texas Hummingbird Roundup out of the Austin headquarters of TPWD.

Increasing Diversity

in the South Texas Plains

By Jesus Franco

The main objective of wildlife and habitat management is to create and maintain balanced, productive and healthy ecosystems. A productive ecosystem is the result of the harmonic interaction between its plant and animal communities, and its soil, water, air and sunlight. As large tracts of land across Texas continue to be fragmented to satisfy the needs of an ever growing human population the creativity of both landowners and natural resource managers is constantly challenged to create or adapt management plans to restore and maintain habitat fragments that support healthy wildlife populations (Wagner, 1997).

In south Texas, small acreage landowners can reap the benefits of healthy ecosystems over the years by applying adequate land management practices suitable to their particular site conditions and their long-term management goals. Food, cover or shelter, and water as well as their proper distribution across the landscape are essential elements to be considered when managing for increased habitat and wildlife diversity.

Managing plant diversity for wildlife. Plants form the basis of food resources and shelter structures for wildlife, therefore, at least a basic knowledge of the plant species—grasses, forbs, shrubs, and trees- present on the land is important in the development of any habitat or wildlife management plan. In general, sites with higher plant diversity will support a greater diversity of wildlife. A diversity of plants that produce foliage, fruit, seeds and nectar during different seasons of the year is highly desirable. Planting a diversity of native brush species will create an increased and varied number of food items available and vegetation layers; an abundance of food and cover options almost always results in a greater diversity of animals be they arthropods, reptiles, insects, birds or mammals.

The reforestation of areas between adjacent wooded patches can reduce bird nest predation and the restoration of native grassland areas linking small vegetated parcels can lessen the effect of fragmentation in favor of birds whose survival depends on relatively large tracts of suitable habitat. Periodic prescribed burning can reinvigorate grass species and control encroaching brush species on grassland sites that are important to game and non-game grassland birds. In these communities mature woody plants can be managed or treated individually to make sure they provide habitat and perching and resting sites for other groups of birds.

Depending on the situation at hand, numerous other management practices, too many to properly address here, are available to the resource manager including control of invasive species, brush control, range planting, deer population management, adequate grazing management systems, just to name a few, can increase wildlife diversity in the south Texas plains.

Providing water for wildlife.Water is critical to wildlife in South Texas and water availability is one of the most important factors in determining abundance and distribution of wildlife. Even if all the other wildlife habitat requirements have been met many populations of wildlife can be reduced or decline if adequate supplies of water are not available.

In South Texas, unpredictable rain is a constant challenge for the natural resource manager trying to prevent wildlife populations from becoming unduly stressed. When water becomes a limiting factor, providing supplemental water is probably the single most important thing a natural resource manager can do to improve wildlife habitat in South Texas.

Some forms in which water can be supplied specifically for wildlife include shallow wetlands, shallow ponds, and flooded fields. Water drippers, water misters, and water falls can significantly increase water use by wildlife, especially birds.

Many existing water systems already available to provide water for domestic livestock can be modified to make water more accessible to wildlife without reducing their usefulness for livestock. Water troughs and open storage tanks can be cleared of obstructions such as fences, braces or vegetation to facilitate usage by bats, swallows, swifts, and nighthawks who drink on the wing over open water (Taylor and Tuttle, 2007). It’s especially import to equip these water structures with adequate wildlife escape structures (also known as wildlife ramps or bird ladders) to prevent the drowning of wildlife that accidentally fall in the water while attempting to drink or bathe. Another simple way to make water available for wildlife on the ground is by fencing off overflow water from windmills.

Landowners seeking technical guidance assistance to increase diversity on their properties are encouraged to contact the TPWD Private Lands Program at http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/landwater/land/private/.

Notes:

- Taylor, D.A.R. and M. Tuttle. 2007. Water for Wildlife; a handbook for ranchers and range managers. Bat Conservation International. Austin, TX

- Wagner, M. 1997. Brush sculpting for nongame birds. Proceedings: Brush Sculptors Symposium. Austin, TX.

Jesus is the Diversity Biologist in the Lower Rio Grande Valley working out of Mission.

Cooperation and Concern Work Together

By Mark Klym

Pepito is flying free again. Not too long ago, he was laying on the side of the hiway, dehydrated and near death. Thanks to the cooperation and concern of wildlife rehabilitators, both in the Lower Rio Grande Valley and some distance away, Pepito was able to recover and join his kind in the skies over Mission.

Did I mention that Pepito is a Mexican free-tailed bat?

When Pepito was found, rehabilitators began calling veterinarians across the Valley trying to find fluids that were needed to keep him alive and revive him. When the animal clinics learned that they were being asked to help a bat, none chose to get involved. That is when the network of wildlife rehabilitators stepped in. A volunteer some distance from the valley was able to ship the fluids overnight to the rehabilitator working with Pepito. Within hours of receiving the fluids he began to recover.

Progress was monitored closely, and within a week it was decided that Pepito should rejoin his colony. In late March I was fortunate to join a group of four Parks and Wildlife staff members as we made our way across Mission from Bentsen Rio Grande Valley State Park to the site of his release. When the transport box was opened, the chatter of bats above the overpass began. As Pepito was held high against the concrete, he climbed out onto the back of the rehabilitators hand and was soon flying free above the colony.

A second Mexican free-tailed bat was found at the scene, this one also a male, but he revived quickly without much assistance, and was soon flying above the colony as well.

The experience reinforced for me the need for education. Even clinics that are noted for animal care were unwilling to assist because the animal was a bat — the needed fluids had to be shipped from outside the area.

Bats are an important part of our ecosystem. In the Rio Grande Valley, with its heavy economic dependence on agriculture, bats are a significant pest control — eating insects that would devastate crops in their absence. Yes, bats that are found on the ground are often rabid, but a bat on the ground is a bat out of place. The incidence of rabies in healthy bat colonies is actually quite low.

So, Pepito is flying again, having survived his close encounter with man to rejoin his colony and to help us by keeping our crops pest free!!

Mark is coordinator of the Texas Hummingbird Roundup out of the Austin headquarters of TPWD.

The Back Porch

Water and wildlife in the marketplace

By Matt Wagner

Texas contains nearly 200,000 miles of streams and rivers.

Thirteen of the state’s 15 rivers flow through metropolitan areas supplying water for more than 22 million people. Twenty percent of those people depend on a single river: the Trinity.

To supply water for people while balancing the needs for wildlife, positive things must happen on the landscape- 95% of which is in private hands.

Consider the relationships of desert fish in a West Texas riparian area, migratory waterfowl dependent upon our playa lakes, endangered salamanders in hill country springs, and the majestic whooping crane whose existence depends on fresh water flows to our bays. These are only a few examples of the fundamental relationship between free-flowing water and wildlife. We could name many, many more.

Each scenario depends on the fate of raindrops as they journey from sky to sea. A raindrop has three options once it reaches the earth’s surface: It can flow across the ground, it can seep into the ground, or it could evaporate. The direction and rate of flow is directly influenced by managers of the land. Rain captured by a vegetated surface seeps downward and makes the grass grow. This in turn kick-starts the life cycle for millions of insects forming the base for a pyramid we call wildlife diversity.

As water continues its downward course past the root zone of grass, wildflowers and trees, it is stored in vast underground basins called aquifers. The Ogallala Aquifer covers parts of 8 states. Ninety-six percent of the water from the Ogallala is used for irrigated agriculture. Some landowners are leasing or selling their groundwater rights to water companies. Under this scenario, the amount of water pumped to grow cotton could be transferred to an urban area because of market demands. There are many questions: what are the impacts to agricultural economies, the farming life style, and alternative land uses? Would the land ultimately revert to short grass prairie?

The Edwards Aquifer is in the news again. During the last legislative session, pumping limits were raised to over 500,000 acre feet per year. Scientists, policymakers, and lawyers are struggling to balance the water demands of a rapidly expanding human population with environmental flows for 8 endangered or threatened species including 2 salamanders, 2 fish, 3 invertebrates and a plant.

But the issue is not about salamanders and cave bugs. It is about the lifeblood of river systems that support a multi-million dollar tourism industry, sustains our bays and estuaries rich in marine life, and meets the demands of a swelling human population.

An acre-foot of water equals 325,851 gallons. At my home in Austin, that amount of water would cost $2,110.65 on my monthly water bill. The economic value of that same amount of water to fish and wildlife cannot be measured. What would the people of Texas be willing to pay for free-flowing rivers and the myriad of life depending on them?

Abundant, clean water in Texas is a public by-product of functioning ecosystems driven by private landowners. Placing a market value on this service is our greatest challenge as the debate surrounding limited water supplies intensifies. There are no easy solutions, but everyone has a stake in the outcome. Part of the solution lies in sacrificing the status quo for the greater good. And in the end, it is the people on the land that determine the fate of a raindrop, and we’ll need to consider them in the economic equation as well.

Matt is the director of the Wildlife Diversity Program working out of Austin.

Green Jay

Did You Know?

The brushland of south Texas is home of some of the richest biodiversity in North America.

Did You Know…

The ocelot, once found throughout south and central Texas at least as far north as the Houston area is now limited to Hidalgo, Cameron, Starr and Willacy Counties.

Javelina

Did You Know…

The last confirmed sighting of a jaguarondi in Texas was made in 1986 near Brownsville, Texas.

Did You Know…

The four counties of the Lower Rio Grande Valley have recorded more butterfly species than other states in the Union.

Did You Know…

Many of the trees, shrubs and other plants of the South Texas Brushlands can be found no where else in Texas.

Curve Billed Thrasher

Did You Know…

Jaguars could once be found in south Texas.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, TX 78744

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, TX 78744