Fall 2013 A publication of the Wildlife Division—Getting Texans Involved

Contentious Coalitions for a Conservation Conundrum

Contentious Coalitions for a Conservation Conundrum

By Donnie Frels

When the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973 was initially passed by the 93rd Congress and signed by President Richard Nixon, it was met with some skepticism by suspicious landowners leery of federal government intrusion in matters involving private property rights. Perhaps nowhere in Texas was this more apparent than the biologically diverse and ecologically sensitive Edwards Plateau ecoregion in Central Texas. Depending on your point of view, perhaps landowners had reason for concern as the stated purpose of the ESA is to protect imperiled species and also "the ecosystems upon which they depend." Others felt the Act may even encourage preemptive habitat destruction by landowners who fear losing the use of their land because of the presence of an endangered species; known colloquially as "Shoot, Shovel and Shut-Up." One example of such perverse incentives is the case of a forest owner who, in response to ESA listing of the Red-cockaded Woodpecker, increased harvesting and shortened the age at which he harvests his trees to ensure that they do not become old enough to become suitable habitat. Add two endangered songbirds to the fray in Central Texas and you get misinformation, contentious meetings, suspicious landowners, and locked gates. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service personnel referred to themselves as "combat biologists" while TPWD wildlife biologists who historically nurtured and enjoyed a trusting relationship on private lands, found themselves without a key.

If Black-capped Vireos (BCVI) were the battle, Golden-cheeked Warblers were the war. Although both occurred in the Edwards Plateau, they were not common neighbors as each searched for very specific habitat requirements within the central part of the state. Simply stated, the warbler preferred old growth while the vireo needed new growth. As fate would have it, Black-capped Vireos (Vireo atricapilla) were of particular interest to a group of enterprising biologists and technicians working on the Kerr Wildlife Management Area (WMA) in western Kerr County. Owned by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, this 6,493 acre research and demonstration area led by Donnie Harmel and Bill Armstrong, was fast becoming known for innovative ideas and a holistic approach to land management focusing on the health of the ecosystem rather than the individual inhabitants.

At that time, cows were king and livestock grazing was the primary use of hill country range land. In order to be credible to landowners most TPWD management plans had to consider livestock grazing and the Kerr WMA had discovered a way for cows and critters to coexist. For promoting attendance at their annual seminars, proper stocking rates and rotational grazing was part of the message while production of big antlered bucks was the carrot. Problem was, cows attracted Brown-headed Cowbirds (Molothrus ater) and cowbirds have a disdain for proper parenting. Instead they prefer foster parents who build cup-shaped nests just like the Black-capped Vireo, to incubate, feed, and raise their demanding offspring - often to the detriment of the rightful recipients. As a result, the Fish and Wildlife Service had cattle grazing on the Kerr in the crosshairs.

Ever diligent, our habitat heroes teamed with Joe Grzybowski of Central State University in Oklahoma to devise a research project investigating the real obstacles to BCVI population growth. Two overwhelming factors emerged: lack of proper nesting habitat and nest parasitism. To address the latter, cowbird trapping proved effective as captured cowbirds off the Kerr perched on the Pearly Gates by the hundreds. Providing proper nesting structure proved problematic.

Although the requisite four foot high nesting structure is readily available for BCVI's in the Edwards Plateau, it seems white-tailed deer and other exotic mammals literally eat them out of house and home. What is one animal's home is another animal's hamburger. Unfortunately for the endangered songbird landowners like deer and in Central Texas they're thicker than bugs on a bumper. With arguably the highest white-tailed deer density in the world and a monetary incentive for landowners to tolerate them, BCVI's literally got the short end of the stick.

Due to long term trends derived from annual vegetation lines and deer surveys, Kerr WMA staff were keenly aware of the predictable cyclic fluctuations - as the deer population increased, vegetative diversity and abundance declined. To address the situation, biologists recommended reducing deer density by half on several occasions. While public hunters enjoyed and appreciated the increased opportunity, success at maintaining the desired density proved temporary as deer from adjoining properties packed their bags and moved to the lush accommodations provided at club Kerr. Staff then reached into their management toolbox and pulled out an uncommon one for a state agency at the time – deer proof fencing. Soon our four-legged friends across the fence would peer through the net wire and opine that the grass is indeed greener on the other side of the fence.

A cadre of camo-clad hunters served as willing participants in the battle for black-capped bungalows. Without the constant browsing pressure of deer and exotic ungulates, low level structure returned to the motte producing species like shin oak and live oak which provide the majority of nesting substrate for these and many other passerines.

With Aldo Leopold's tools of wildlife management firmly in place, the Kerr WMA was now operating like a well-tuned ecological machine.

- Prescribed burning was reducing ashe juniper while rejuvenating grass and brush species

- Rotational grazing proved the importance of rest and recovery for grass species while utilizing the range properly

- Hunters and the high fence maintained deer density at appropriate levels so browse and forbs flourished

- Cowbird trapping was reducing nest parasitism not only for BCVI's but numerous species of other songbirds

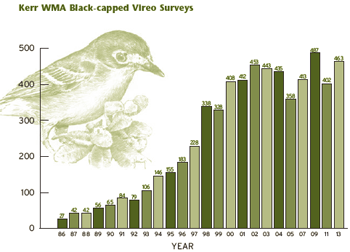

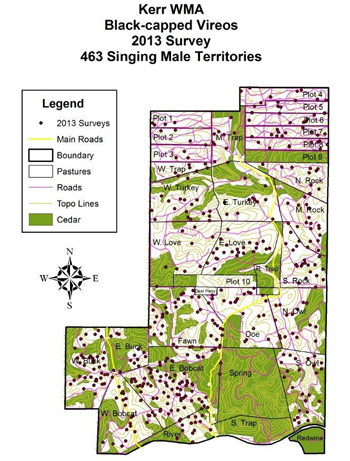

While avoiding the temptation to concentrate management efforts on just birds, cows, or deer, Harmel and Armstrong built an ecosystem capable of producing a variety of desirable products appreciated by both birders and hunters. A quick glance at the graphs provided will attest to the success of the ecosystems approach to proactive BCVI management rather than strict preservation of existing limited habitat. As Armstrong was fond of saying, "Black-caps are the poster child for good deer management".

Today, public opinion of the Endangered Species Act varies depending on personal perspective. Generally speaking, I would surmise a definite shift in general landowner attitudes with regards to private property impacts. Where landowners once feared the yoke of federal regulation, many now embrace the Act as a vehicle for property protection when threatened by proposed road or utility projects while others enjoy the monetary benefits now associated with recreational birding for rare and endangered species.

Often in nature beneficial associations formulate over time out of necessity. Although hunters and birders both enjoy a quest for quarry and an appreciation for things wild, they often seem to possess opposing ecological ideologies. Understanding the niche each occupies in natural resources conservation and management may assist us all in effectively navigating the road to recovery for our endangered resources.

Donnie is Wildlife Management Area Project Leader responsible for the Kerr, Muse and Mason Mountain WMAs. He works out of the Kerr WMA.

An Endangered Bat with a Tequila Connection

An Endangered Bat with a Tequila Connection

Photo © Carson Brown

By Jess Lucas

If you still find you can't see bats in a positive light, consider this. Texas has a very special resident, the Mexican long-nosed bat, without which there would be no tequila.

The Mexican long-nosed bat (Leptonycteris nivalis) makes a seasonal foraging trek to west Texas every year, migrating north from Mexico. While most bats found in Texas are insectivorous (insect-eating), this bat is specially built to consume nectar and pollen, primarily from the flowers of the agave. You may already know that tequila is made using agave plants, but you likely didn't know bats have made it all possible.

The migration of the Mexican long-nosed bat appears to follow the range of the agave plant and the progression of the plants as they flower. The agave opens its flowers at night, and attracts the bats with large amounts of nectar. When the bats are feeding on the nectar and pollen, they pick up some pollen on their fur and faces, and transfer the pollen on to the next plant they visit, cross-fertilizing the agave. The bats and the agave are mutually dependent - the bats need the food, the plants need to reproduce. Likewise, the tequila industry benefits from the genetic diversity of the agave plants, which helps build resistance to disease and pests.

Photo © Nick Hristov

However, this relationship is in danger. In parts of the bats' range (primarily in Mexico and Central America) wherever bat roosts are found, entire colonies (usually containing multiple species) have been deliberately poisoned and roosts have been vandalized, primarily because of social stigmas regarding bats. In Latin America, vampire bats are considered harmful to livestock and stigmatized as being "evil", and all bats seem to get the same treatment. Unfortunately, Mexican long-nosed bats were hard hit by the blanket exterminations.

Additionally, the range-wide source of the agave plants on which the bats depend has also been decimated, and the continuous migration and foraging route of the bats now has gaps. In many cases, the loss of agave plants can be attributed to the production of regional bootleg liquor. To make the liquor, the plant is "beheaded" - the center of the plant (the part that will form a flower stalk) is cut out, and when the plant base is deemed ripe it is trimmed and cut off the ground. This cone-looking part of the plant is full of fluids used to produce liquor. Unfortunately, flowering is a rare event in agaves, with some species gaining the name "century plant" for the time it takes them to bloom. Additionally, each plant only blooms once, and then the agave dies. When agaves are cut before blooming, a loss of genetic diversity for the agave species occurs - as does a loss of feeding opportunity for bats.

These two major issues led to the addition of the Mexican long-nosed bat to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Endangered Species list in 1988. Incidentally, the species is now protected wherever found in the U.S., and additionally, Mexico has afforded it similar protection.

Fortunately, over the past 20 years, educational efforts by bat conservation groups have helped turn public opinion on bats, and conservation efforts have begun on the Mexican side of the border, improving the situation. Frequent population counts on the species have shown the situation is less dire than it was in the past.

Photo © Carlos Luna

The Mexican long-nosed bat is a part-time resident of west Texas, where it has been captured by researchers in Brewster and Presidio counties. It is known to roost in caves and mines, but there is only one known roost for the species in the United States, and that is within Big Bend National Park. This colony varies in size, but up to 10,650 individuals have located to the cave seasonally.

If you live in the Trans Pecos, you can help support the Mexican long-nosed bat in a couple of ways. Locate a reputable source for local agave plants, and find a place in your garden for them. It will take years for the agave to bloom, but they provide nice greenery in the meantime. When the flower stalk does appear, it will provide food for bats, moths, and many other species.

If you don't have space for an agave plant, or desire a quicker turnaround, you can hang out a hummingbird feeder or two, and there's a chance the bats may visit the feeders for a quick snack at night.

Jess was a non-game data specialist working with the Bat Working Group out of the Austin headquarters office.

The Endangered Species Act Helps Restore the Endangered Kemp's Ridley Sea Turtle

By Donna J. Shaver, Ph.D.

The first published record of a Kemp's ridley nesting in the wild was an individual found nesting in 1948 at what later became PAIS. Although PAIS is the most important Kemp's ridley nesting beach in the U.S, by far most nesting by this species occurs in Mexico. However, for many years, biologists did not know where most of the Kemp's ridley population nested. A Mexican engineer filmed a synchronous nesting emergence of Kemp's ridleys in 1947 at Rancho Nuevo in Tamaulipas, Mexico. Dr. Henry Hildebrand from Corpus Christi, Texas discovered that film and showed it at a herpetological conference in the early 1960s. Based on this film, the number of turtles nesting at that time was estimated to be over 40,000.

Mexican biologists began studying and protecting the nesting turtles and nests on the beach at Rancho Nuevo starting in the mid-1960s, but they found that the population had plummeted. Despite continuing protection by the Mexican government, by the mid-1980s the population had decreased to an estimated 300 nesting females. This precipitous decline was due primarily to poaching of eggs for use as a supposed aphrodisiac and incidental capture of juveniles and adults by shrimp trawling. As a result of this drastic population decline, Kemp's ridley sea turtle was listed as endangered throughout its range on December 2, 1970, and the species has received Federal protection under the ESA for the last 40 years.

The purpose of the ESA is to protect and recover threatened and endangered species and the ecosystems they depend upon, so that they ultimately no longer need protection under the ESA. The ESA provided the framework and authority for the U.S. to aid with recovery efforts for this imperiled species. In 1977, a bi-national Kemp's Ridley Recovery Program was formed involving the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), National Park Service (NPS), Instituto Nacional de la Pesca of Mexico, and Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD). As part of this bi-national program, the U.S. joined into the on-going protection efforts on the nesting beach at Rancho Nuevo. In addition to trying to protect the nesting population in Mexico, another goal of the bi-national program was to form a secondary nesting colony of Kemp's ridley turtles at PAIS, as a safeguard against extinction in case a political or natural disaster was to occur in Mexico. PAIS was selected as the location for this effort since the nesting habitat is preserved and protected as a National Seashore and it is within the documented historic nesting range of the species.

From 1978-1988, 22,507 Kemp's ridley eggs were collected at Rancho Nuevo, packed in North Padre Island sand, and transported to PAIS for hatching. The hatchlings were released on the PAIS beach, allowed to crawl into the surf, and captured using aquarium dip nets after a brief swim in the Gulf of Mexico. It was hoped that this exposure to Padre Island sand and surf (termed "experimental imprinting") would cause the turtles to return to PAIS to nest when they reached adulthood. The captured hatchlings were transported to the NMFS Laboratory in Galveston, Texas, where they were reared in captivity for 9-11 months. This "head-starting" allowed the turtles to grow large enough to be tagged for future recognition and avoid most predators after release. Finally, the one-year-old turtles were released permanently, most into the Gulf of Mexico off Mustang and North Padre Islands.

PAIS began patrols to find and protect nesting Kemp's ridleys and their eggs on North Padre Island in 1986. Patrol programs began later on other Texas beaches, and today patrols are conducted to some extent on all Texas Gulf of Mexico beaches annually, from April through mid-July. The six patrol programs in Texas are administered by Texas A&M University-Galveston, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, ARK, NPS, and Sea Turtle, Inc. Hundreds of dedicated staff members and volunteers conduct these patrols with the support of several organizations such as TPWD. Sea Turtle Restoration Project sponsors a toll-free telephone number (1-866-TURTLE5) to report nesting and stranded sea turtles in Texas.

Patrols are conducted primarily during daylight hours since Kemp's ridleys nest mostly during the day. Most nests are found by the sea turtle monitoring patrols, but some are found by other individuals working or recreating on the beach, especially in the developed areas of the coast. Eggs from nests found on PAIS and northward in Texas are transported either to the PAIS incubation facility or protected enclosures on the beach called corrals and the resulting hatchlings are released at PAIS, to help reinforce the bi-national effort to form a secondary nesting colony there. Eggs from South Padre Island are brought to a protective corral on South Padre Island for incubation, and the emerging hatchlings are released nearby. The public is invited to attend many of the hatchling releases held at PAIS and on South Padre Island, free-of-charge.

Texas waters also provide very important habitat for Kemp's ridley turtles. Kemp's ridleys forage in Texas Gulf of Mexico and bay waters at various stages of their life cycle. Adult males and females feed in nearshore Gulf of Mexico waters, and a large portion of the adult female population uses these waters as a migratory corridor between foraging grounds in the northern Gulf of Mexico and nesting beaches in Mexico and Texas.

The Kemp's Ridley Sea Turtle Recovery Plan not only focuses on protection of the turtles on nesting beaches, but also in their marine habitat where these turtles spend the majority of their lives. This is addressed through the requirement of shrimp fishery to use turtle excluder devices (TEDs) to prevent incidental capture. Shrimping closures established by TPWD during the Kemp's ridley nesting season in Texas have also been extremely beneficial to the conservation of the species, while at the same time allowing shrimp to grow to a larger, more valuable size prior to market.

Several other recovery task priority items are also outlined in the Kemp's Ridley Recovery Sea Turtle Plan. One of these is operation of the Sea Turtle Stranding and Salvage Network. Many groups and individuals help find and document sea turtles stranded (washed ashore, alive or dead) in the U.S. and Mexico. Live stranded turtles are transported to rehabilitation facilities to receive care, with the objective of returning as many of those turtles as possible to the wild so that they can contribute to the population.

After years of effort from multiple agencies and Federal protection under the Endangered Species Act, Kemp's ridley nesting has increased substantially from the population low of only 702 nests world-wide in 1985. A record 209 nests were recorded in Texas (including 106 at PAIS) and nearly 22,000 in Mexico during 2012. Some turtles from the experimental imprinting and head-starting project have been confirmed nesting in the wild, mostly on North Padre and Mustang Islands. They have contributed to the increase in nesting in Texas during recent years, but by far most nests found in south Texas are from turtles from the wild stock that are repopulating the area.

The substantial growth of the Kemp's ridley population is encouraging. The Kemp's ridley population can be down-listed to threatened status after a number of milestones outlined in the Kemp's Ridley Sea Turtle Recovery Plan are met. One of those milestones is 10,000 females nesting in a season. It will take more years to achieve this goal since each nester produces 2.5-3.0 nests within a season, and the rate of nesting increase has noticeably slowed since 2009. In order to continue to make progress towards population recovery, the ultimate goal of the ESA, conservation efforts in Mexico and the U.S. must continue.

Donna J. Shaver is Chief of the Division of Sea Turtle Science and Recovery for the National Park Service at Padre Island National Seashore near Corpus Christi, Texas.

References:

National Marine Fisheries Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and SEMARNAT. 2011. Bi-National Recovery Plan for the Kemp's Ridley Sea Turtle (Lepidochelys kempii), second revision. National Marine Fisheries Service. Silver Spring, MD 156 pp. + appendices.

Shaver, D.J. 2005. Analysis of the Kemp's ridley imprinting and headstart project at Padre Island National Seashore, Texas, 1978-88, with subsequent Kemp's ridley nesting and stranding records on the Texas coast. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 4(4):846-859.

Shaver, D.J. and C. Rubio. 2008. Post-nesting movement of wild and head-started Kemp's ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys kempii) in the Gulf of Mexico. In: Endangered Species Research 4:43-55.

Shaver, D.J., K. Hart, I. Fujisaki, C. Rubio, A.R. Sartain, J. Pena, P.M. Burchfield, D. Gomez Gamez, and J. Ortiz. 2013. Foraging area fidelity for Kemp's ridleys in the Gulf of Mexico. Journal of Ecology and Evolution doi: 10.1002/ece3.594.

Texas Prairie Dawn Conservation Success in Houstlandia

By Jason Singhurst

Prairie dawn is restricted to the Gulf Coastal Prairies in the upper coast of Texas with its core range centered on Houston (Fort Bend and Harris Counties) with two disjunct isolated prairie populations, one in Greg County and one in Trinity County. The species was first collected in 1889 near Hockley, Texas, in Harris County by F. W. Thurow. Hockley is renowned by many geologists for its famed Hockley Salt Dome, a mound or columns of salt that rise above parent geology to the surface. Until 1970, the prairie dawn species appeared to have vanished from Texas botany. It is not listed in Texas Plants - A Checklist and Ecological Summary by Dr. Frank Gould (1962). Correll and Johnston (1970), in the Manual of the Vascular Flora of Texas, state "Rare in sandy soils near Hockley and Houston, Harris County, probably extinct (no known collections after 1900)." In 1981, James W. Kessler discovered three populations growing in "buffalo wallows" or small depressions in Harris County, these being the first known collections of this species since 1889-90 (Mahler 1983).

Prairie dawn is limited to 'saline prairies' with cryptogamic soils within the Houston Coastal Prairie dominated by gulf coast muhly (Muhlenbergia capillaris). Many of the species that occur in these rare saline prairies are absent from or uncommon in adjoining vegetation. These soils are shallow, saline, and support a moderate diversity of annual and perennial herbs that commonly occur in barren slicks and at the base of mima mounds (Bierner 2005). It is thought that the natural pattern of disturbance (droughts, fires, and floods) is necessary to maintain the areas, though the exact role disturbance may play is not clear.

Prairie dawn was listed as endangered by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (1986). The founding information was assembled by Bridges (1988). Approximately 60 occurrences (TxNDD 2013) of prairie dawn have been recorded, these primarily in Harris County. Unfortunately, many of these occurrences have been lost to development. Today, there are only 11 occurrences; nevertheless huge conservation strides have moved the bar forward towards recovery of this species in 'Houstlandia' (greater Houston area).

After the 1981 rediscovery, prairie dawn was documented at Addicks and Barker Reservoirs in 1986, lands owned by the United States Army Corp of Engineers (USACE). Addicks and Barker Reservoirs are located near the intersection of Interstate 10 and State Highway 6, in the upper watershed of Buffalo Bayou. The 26,000 acres that makes up Addicks and Barker Reservoirs are publically accessible and provide flood damage reduction along Buffalo Bayou downstream of the reservoirs and through the center of the City of Houston. This amazing tract of land also contains large populations of prairie dawn. Since the 1986 discovery, extensive botanical surveys have been conducted, which has resulted in many populations of prairie dawn found throughout this landscape. USACE has conducted annual monitoring surveys and population estimates. USACE has also utilized Geographic Information Science (GIS) and Global Position System (GPS) tools to map populations and provide this data to Texas Parks and Wildlife Department's Texas Natural Diversity Database. USACE has also mapped invasive plants that occur adjacent to or within the saline prairies that prairie dawn inhabits. USACE is utilizing this digital data within their natural resource plan with application to reduce invasive plants such as Chinese tallow, Macartney rose, and deep-rooted sedge that threaten prairie dawn populations.

Katy Prairie Conservancy (KPC), is a local land trust organized for the preservation of the remaining Katy Prairie remnants in northwest Harris County, near the city of Katy. KPC owns and manages a total of 18,000 acres of conservation land which includes two extremely significant prairies, Warren Prairie (285 acres) and Jack Road Prairie (511 acres) that were purchased as conservation areas to preserve two large prairie dawn populations. Warren and Jack Road Prairies lie adjacent to the Hockley Salt Dome. These prairie dawn populations have been surveyed almost annually since 2003, and in 2008-2009 a census was conducted by Wesley Newman, KPC Conservation Stewardship Director, Nancy Shackelford (University of Western Australia) and Jason Singhurst (Botanist, TPWD) to estimate the population size.

A population of prairie dawn documented back in 1988 was purchased through mitigation funds and is now owned by Harris County Parks and called Prairie Dawn Preserve. This preserve is being managed by Anita Tiller, a botanist with Mercer Arboretum, in north Harris County.

Harris County Parks also owns a tract of land in southeast Harris County called the Native Coastal Prairie Preserve adjacent to Ellington Field Airport. This prairie landscape is also referred to as Armand Pothole and sits on a salt dome. This preserve, also purchased through mitigation funds, had been neglected for several years which has allowed invasive woody plant growth (primarily Chinese tallow). However, recent discussion with Harris County Parks and Coastal Prairie Partnership to conduct ecologically sound management of invasive plants within the preserve looks promising.

Harris County Flood Control owns Willow Water Hole Prairie in south Harris County and is restoring this natural pocket prairie and planning interpretive signage. Not yet open to the public, plans for public visitation are in the works.

These are some of the gold star highlights with respect to migration towards recovery of prairie dawn throughout its restricted global range. Prairie dawn is also accompanied in the highly restricted saline prairie habitat with several other globally rare endemic plants, including coastal gayfeather (Liatris bracteata), Houston daisy (Rayjacksonia aurea), Texas windmill grass (Chloris texana), and three-flowered broomweed (Thurovia triflora). Therefore, each conservation success for prairie dawn benefits one or more additional globally rare plants. The road to full recovery for prairie dawn since its rediscovery in 1981 is still far out on the horizon, but these land acquisitions, restoration, management, and partnerships are making great progress for this unique yellow flowering Texas wildflower.

References:

Bierner, M.W. 2005. Hymenoxys. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993+. Flora of North America North of Mexico 12+ vols. Oxford Univ. Press, New York and Oxford. Vol.21.

Bridges, E.L. 1988. Endangered species information system species workbook for Hymenoxys texana, part II. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. 43 pp.

Correll, D.S. and M.C. Johnston. 1970. Manual of the Vascular Plants of Texas. Texas Research Foundation, Renner. Gould, F. W. 1962. Texas Plants - a checklist and ecological summary. MP-585. Tex. Agri. Exp. Sta., College Station.

Gould, F. W. 1962. Texas Plants - a checklist and ecological summary. MP-585. Tex. Agri. Exp. Sta., College Station.

Mahler, W.F. 1983. Rediscovery of Hymenoxys texana and notes on two other Texas endemics. Sida 10:87-91.

Texas Natural Diversity Database (TxNDD), 2013. Wildlife Diversity Program, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Austin, Texas.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1986. Determination of endangered status for Hymenoxys texana. Fed. Reg. 51(49):8631-8633.

Jason Is a botanist with Texas Parks and Wildlife Department working out of the Austin Headquarters.

Threatened and Endangered Fishes of Texas

By Gary Garrett and Megan Bean

Unfortunately however, we have already lost as many fish species (8) in Texas as are now listed. One, Rio Grande Silvery Minnow, was extirpated but is now in the process of being repatriated. An additional 50 species of freshwater fishes are recognized by TPWD as Species of Greatest Conservation Need (face the threat of extirpation or extinction but lack legal protection). In 1991 a study by TPWD and the University of Texas revealed that 25% of the native freshwater fishes of Texas were already lost or faced extirpation or extinction. Today that number has grown to 40%.

We hope the Rio Grande Silvery Minnow (Hybognathus amarus) story is one with a happy ending. This fish used to be one of the most common fishes in the Rio Grande, from the Texas coast into northern New Mexico. By the late 1960s it had disappeared from the Texas part of its range and all that remained in New Mexico was in a short stretch of river around Albuquerque. We may never know what caused their demise, but it was likely a combination of factors such as drought, pollution, dewatering, etc. In 1994 it was listed as endangered and in December 2008, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park Service, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, and other partners began releasing silvery minnows into their former home in Big Bend. These recovery actions are designed to reestablish the minnow in Texas with the ultimate goal of eventually removing the need to have it listed. So far, we have released over two million young silvery minnow and biologists continue monitoring (and hoping) for a self-sustaining population.

Many of our threatened and endangered species occur in the relatively harsh habitats of West Texas. Our portion of the Chihuahuan Desert region contains a wide variety of habitats and many uniquely adapted plants and animals. Unfortunately, the limited aquatic habitats of this ecosystem have undergone substantial modifications in the last hundred years. One of the most heavily impacted habitats is the desert springs and their associated wetland habitats (ciénegas). These ecosystems were seldom damaged on purpose; put simply, water is rare in the desert and people want it for a variety of uses. The ways in which ecosystems have been destroyed include grazing and watering livestock, draining to move water more efficiently to agricultural fields, and over-pumping of aquifers.

Over half (63%) of the native fishes of the Chihuahuan Desert are threatened with extinction or are already lost. Documented extinctions from this area include the Maravillas Red Shiner (Cyprinella lutrensis blairi), the Phantom Shiner (Notropis orca), the Rio Grande Bluntnose Shiner (Notropis simus simus), and the Amistad Gambusia (Gambusia amistadensis). Extirpations include the Rio Grande Silvery Minnow (Hybognathus amarus), Pecos Bluntnose Shiner (Notropis simus pecosensis), Rio Grande Cutthroat Trout (Oncorhynchus clarki virginalis) and Blotched Gambusia (Gambusia senilis) in Texas.

Here is a brief summary of the remaining federally listed fishes of Texas:

Photo © G. Sneegas

Devils River minnow (Dionda diaboli) - Threatened 1999

The Devils River Minnow was originally discovered and described from Baker's Crossing on the Devils River, Val Verde County. It is known to occur in Texas in the Devils River, San Felipe Creek, Sycamore Creek and Pinto Creek. They have been extirpated from Las Moras Creek, Kinney County. There are also historic records of occurrence in two small streams in Coahuila, Mexico, the Río San Carlos and Río Sabinas. Their current status in Mexico is unknown but, at best they are thought to be rare. Historically, the Devils River Minnow was one of the most abundant fishes in the Devils River. Their numbers began dropping in the 1970s and they became quite rare. The upper and lower portions of its range in the Devils River are gone, due to reduced spring flows in the headwaters and impoundment of Amistad Reservoir in the lower portion. The biome created by the overlap of the Chihuahuan Desert, Edwards Plateau, and South Brush Texas ecosystems yields a unique fish fauna of which the Devils River minnow is part. A Conservation Agreement was developed in 1998 among the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, the City of Del Rio and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and is designed to foster research to 'eliminate or significantly reduce the probability that potential threats to the minnow will actually harm this species and to recover populations of the minnow to viable levels'. Although first proposed for endangered status under the Endangered Species Act in 1978, the Devils River minnow wasn't listed until 1999. A critical subset of the range of D. diaboli is now owned by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department and the Nature Conservancy of Texas.

The other locations for Devils River Minnow have been severely affected by drought and water use (Pinto Creek and Sycamore Creek) and establishment of the exotic armored catfish (San Felipe Creek).

Photo © G. Sneegas

Arkansas River Shiner (Notropis girardi) - Threatened 1999

The Arkansas River Shiner is a small, streamlined minnow that has evolved for life in shallow braided channels of wide sandy prairie rivers in the Arkansas River system. Like many prairie minnows, they spawn after heavy summer rains and their eggs drift with the water current and develop as they are carried downstream. Historically, the Arkansas River Shiner occupied all of the major river tributaries to the Arkansas River in the Great Plains including the Cimarron, North Canadian and Canadian rivers as well as the Arkansas River. This species has been in decline since the 1950s, and has been extirpated from nearly 80% of its historic range. The current range of the Arkansas River Shiner is mainly in the Canadian River in Oklahoma, western Texas and eastern New Mexico. An isolated population occurs in the Pecos River in southwestern Texas where they were accidentally introduced. Channelization of the Arkansas River has permanently altered and eliminated suitable habitat and is largely responsible for the extirpation of the species within the Arkansas River in Arkansas and Oklahoma. In addition, habitat loss, alteration of river flow from reservoir construction and pumping from the watershed for irrigation has had detrimental effects.

Photo © R. Edwards

Big Bend Gambusia (Gambusia gaigei) - Endangered 1967

Big Bend Gambusia evolved in spring habitats near Boquillas Crossing and Rio Grande Village in what is now Big Bend National Park. These springs were lost in the 1950s and today, all G. gaigei are descendants of the three individuals rescued by Dr. Clark Hubbs in 1956. At present, several thousand Big Bend Gambusia inhabit two spring pool refugia and a spring-fed drainage ditch. The limited quantities of warm spring waters available, park campground development in the area and the loss of natural habitats in Boquillas Spring and Graham Ranch Warm Springs limit this species recovery. A new refuge (Clark Hubbs Refuge) was constructed from a separate water source from the Spring 1 refuge. This new refuge was stocked twice in 2010 with approximately 200 fish each time. Recent sampling using minnow traps shows many Big Bend Gambusia of all life stages in both of the refuge ponds.

San Marcos Gambusia (Gambusia georgei) - Endangered 1980; likely extinct

The San Marcos Gambusia was found only in the headwaters of the San Marcos River, within the City of San Marcos. The species was found in collections taken in 1884 and in later collections (as a hybrid with G. affinis) taken in 1925. Since that time, nearly every specimen of G. georgei has come from approximately 2 miles downstream from the headsprings in a ½ mile stretch of the San Marcos River. During an extensive study of the species during the late 1970s, G. georgei was extremely rare accounting for only 0.09% of all Gambusia captured. Gambusia georgei lived mostly over muddy but not silted substrates, and generally in shaded or partially shaded habitats. The San Marcos River has been extensively sampled throughout the past five decades; the last individual of this species was taken in 1982. The San Marcos Gambusia is, in all likelihood, extinct.

Clear Creek Gambusia (Gambusia heterochir) - Endangered 1967

The species was first collected in the headwaters of Clear Creek, Menard County, in 1953 and is restricted to this spring environment. Clear Creek arises from a series of springs on a limestone bluff 10 miles west of Menard. Clear Creek was a clear, spring influenced creek that flowed for about 3 miles to its confluence with the San Saba River. We assume that most of the creek was inhabited by springrun species such as the Clear Creek Gambusia and associated plants and animals. Today, thousands of Clear Creek Gambusia occupy the 2½ acre head pool formed by a small earthen 6-foot wide dam built in 1880. Another dam was constructed downstream from the head pool in 1933 that formed a much larger pool that abuts the 1880 dam. The downstream pool is occupied by large numbers of Western Mosquitofish (G. affinis), which compete and hybridize with G. heterochir. These two sympatric Gambusia live in different environmental conditions: stenothermal springpool water with neutral pH favors G. heterochir and eurythermal water with a pH near 8 in the downstream pool favors G. affinis. Both species flourish in either environment but competition favors the fish in their respective environments. At present, G. heterochir is very abundant in the head pool but is threatened by diminished spring flows from water withdrawals from the Edwards-Trinity aquifer as well as deterioration of the earthen dam.

Pecos Gambusia (Gambusia nobilis) - Endangered 1970

Gambusia nobilis was described 1853 from Leon and Comanche springs, Pecos County. The species is endemic to the Pecos River basin in southeastern New Mexico and western Texas. At present, the species is restricted to four main areas, two in New Mexico and two in Texas. The populations that once existed at Leon Springs and Comanche Springs were lost when these springs went dry during the mid-1950's. Pecos Gambusia populations can be dense, ranging from 27,000 to 900,000 individuals in the isolated environments in which they occur. Pecos Gambusia usually inhabits stenothermal springs, runs, spring-influenced ciènegas, and irrigation canals carrying spring waters. One or two other Gambusia species may also be found in association with G. nobilis but these segregate by habitat. Pecos Gambusia face severe threats from spring flow declines and habitat modifications throughout their range and from competition with introduced Largespring Gambusia (G. geiseri). Efforts have been made to improve habitat in the Balmorhea area including constructing a small refugium canal and artificial ciènegas in Balmorhea State Park, and a small ciènega at Phantom Spring. A renovation of the Diamond-Y Draw in 1998 removed G. geiseri from that system. As with so many of our Texas fishes and especially with the spring endemics, the primary threat to the survival of the Pecos Gambusia is the loss of the spring-fed waters that provide their habitat.

Leon Springs Pupfish (Cyprinodon bovinus) - Endangered 1980

The type locality, Leon Springs, no longer exists due to impounding and groundwater pumping and the species was presumed extinct. In 1965, Cyprinodon bovinus was rediscovered in Diamond Y Spring, and the species was subsequently found in a small segment (5-6 miles) of Diamond Y Draw, a flood tributary of the Pecos River approximately 10 miles downstream from the site of Leon Springs. The population size in Diamond Y Draw is estimated to be less than 10,000 adults. Cyprinodon bovinus is at risk of introgressive hybridization with Sheepshead Minnow (C. variegatus), which was first found at Diamond Y Draw in 1974, likely due to bait transport. Within one year an extensive hybrid swarm existed throughout the lower segment of the creek. There is also evidence of an additional introduction of C. variegatus in the late 1980s or early 1990s. Hybrid eradication efforts (rotenone and selective seining) took place in 1976 and 1978 and reduced genetic contamination. In 1998 the upper watercourse was renovated with antimycin. In 2000 the lower watercourse was renovated by intensive seining. After renovation, C. bovinus from a genetically pure captive stock at Dexter National Fish Hatchery were released into each location. Both renovation methods succeeded in reducing frequencies of non-native alleles. Most of the habitat is now owned by The Nature Conservancy of Texas, who bought the 1,500 acre, Diamond Y Spring Preserve in 1990. There is an ongoing project at the Preserve to restore quality habitat. Continued threats include loss or alteration of habitat and pollution.

Comanche Springs Pupfish (Cyprinodon elegans) - Endangered 1967

Cyprinodon elegans originally inhabited two isolated spring systems approximately 55 miles apart in the Pecos River drainage of west Texas. Groundwater pumping caused the type locality, Comanche Springs, Pecos County, to go dry in 1954 and that population is extinct. The other population is restricted to the Balmorhea springs complex and three artificial refugia, all near Balmorhea, Reeves County. These fish are well adapted to life in the desert and did especially well in ciènegas. Beginning in the mid-1870s, ciénegas were drained and spring flows diverted into irrigation networks.

This habitat is highly unnatural, ephemeral and wholly dependent upon local irrigation practices and other water-use patterns. Cyprinodon elegans now lives in modified springs, various irrigation canals and refugia designed to resemble the original natural habitat. The species is wholly dependent upon failing spring flows in the area and suffers as well from threats of hybridization and competition with introduced Sheepshead Minnow (C. variegatus). A small refugium canal was constructed in 1974 in Balmorhea State Park. In 1993, the Bureau of Reclamation constructed a modified 120-yard canal at nearby Phantom Lake Spring designed to resemble a portion of a ciénega. Reduced spring flows caused this refugium to fail several years later, but US Fish & Wildlife Service recently created a new, small ciènega in its place. In cooperation with local residents and farmers, in 1996 the construction of the 2 1/2 acre San Solomon Ciénega was completed at Balmorhea State Park. In 2011, an additional ciénega was created at the Park. Designed to resemble and function like the original ciénega, the native fish fauna, including C. elegans, has flourished. These new habitats have increased numbers and security for the species, but each remains dependent on spring flows.

Fountain Darter (Etheostoma fonticola) - Endangered 1970

Fountain Darters are specifically adapted to the thermally constant headwaters of the Comal and San Marcos rivers and are found nowhere else. They require clean, spring-fed waters with aquatic vegetation like filamentous algae. They are primarily threatened by reduction of spring flow, resulting from drought and water withdrawals from the Edwards Aquifer, but other forms of habitat loss as well as pollution and introduction of exotic species are also of concern. The Comal River population was completely wiped out during the drought of the 1950s because the springs totally stopped flowing. In 1975, Fountain Darters from the San Marcos River were put into the Comal River to reestablish the population.

Gary Garrett is Program Director for Watershed Conservation at Texas Parks and Wildlife working out of Mountain Home. Megan is a Watershed Biologist.

Bald Eagle Recovery in Texas

By Brent Ortego

The Bald Eagle is one of the top avian predators in Texas and they primarily feed on fish, waterfowl and reptiles. It historically nested in the eastern 1/2 of Texas in large trees near creeks, rivers and lakes. It was viewed as a threat to livestock industry during the 1800's and many were "handled" by livestock producers. Scientists did not start studying eagles in Texas until the early 1900's, over 300 years after Texas was occupied by Anglos. No estimate was ever made during that period of the number of pairs nesting in the State. Eagle populations likely were much lower than historically during the early 1900's because of centuries of Anglo occupation which removed the old growth forests and killed perceived depredating birds. Eagle numbers declined further after World War II when agricultural pesticides like DDT became prevalent. The Bald Eagle was placed on the federal endangered species list in 1967 and was removed in 2007 when the population had recovered at a national level.

In some parts of Texas the recovery is still in progress. While other areas like large reservoirs in East Texas bordered by national forests and rivers near the Coast, the population appears to be healthy.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) started studying the Bald Eagle in 1971 when there were only 4 known nests left in the State. Texas eagles typically show up on their breeding territories in October, lay eggs in November, hatch young near New Years and young fledge in April. More northern nesters and younger birds normally start the nesting cycle a little later.

Early research efforts by TPWD were focused on monitoring nesting populations. Later research expanded to study food habits and distribution of young birds. Food consumption was typical for eagles outside of Texas, except turtles were higher in the diet. Texas eagle foods were primarily coots, ducks, geese and fish like carp and catfish. Turtles were common in the diet and it was postulated that warm clients made them more available.

It was noted early in the research that most of the eagles left their breeding territories after nesting. In order to determine where our birds went, 138 young eagles were banded to study their movements. Most banded eagles showed a gradual spring-summer northward migration after the nesting season and birds migrated as far north as Canada before returning in the fall. Nine of the banded young eagles returned to nest in Texas. This means that many of the marked birds dispersed in the United States. TPWD received reports of 3 of the birds where they likely nested outside of the State. One bird ended up nesting on top of a mountain in Arizona, another one died in Arkansas and the third was found under a power line in Florida during periods they would have been expected to be nesting.

Additional research showed that the typical eagle nest is only used about 4 years. Texas is fortunate to have numerous large trees near water and this gives the eagles options in picking nest sites. One major snow storm and a hurricane occurred during our studies and neither was shown to impact the population.

Recovery of the Bald Eagle population was slow following the restriction of using DDT during the late 60's. The 4 remaining active nests were located along coastal rivers in 1971. By 1981, TPWD knew of 8 nests with most being near the Coast. This location trend continued through 1991 with 22 nests along the Coast and 14 elsewhere. By 2001, many eagles found the large inland reservoirs bordered by national forests to their liking and they started nesting there in significant numbers with 55 nests in East Texas in 2001, 47 on the Coast and 12 elsewhere. Our last state nesting survey was in 2005 and TPWD continued to track reports from the public of nest locations. In 2007, TPWD knew of 62 nests along the Coast, 90 in East Texas, 36 additional nests east of I-35, 3 in the Hill Country and 2 further north for a total of 193 nests. This was a great population recovery for a species in the state that 36 years earlier had only 4 nests.

What is the future of the Bald Eagle in Texas? There are still opportunities and threats for the species. The species is attracted to surface water and Texas has significant acres of reservoirs, rivers and creeks, and Texans are planning for more lakes. There is an expanding aquaculture business in Texas and a number of eagles are starting to use commercially grown fish for food. As an example, several eagle nests today are located near catfish farms. Most pesticides are regulated and they are not expected to be a major factor. On the negative side, new power lines are being constructed each year and many pose threats to eagles. There is the possibility that existing and newly discovered diseases will impact the population. Riparian forest management will be an issue in the future as more and more forests near the water's edge are cleared. Much of the riparian landscape is being occupied by residential areas.

Not all eagles are tolerant of people and this will limit their potential population size. There is hope that eagles will eventually become used to people. The Houston metropolitan area is a good example of this with 15 eagle nests too date positioned near lake shores, bayous and green belts. However, it is the only metro area in Texas with any number of eagles nesting within its boundaries.

Brent is the Diversity Biologist in Region 7 working out of Victoria.

From Fatmuckets to Pimplebacks

By Marsha May

Their main diet consists of bacteria and plankton (tiny plants and animals). They keep the water clean and clear as well as serve as habitat for other aquatic animals such as benthic microinvertebrates (hellgrammites, dragonfly larva, damselfly larva, etc.). Why are we losing these important animals? Scientists believe that there are a number of reasons, but the number one reason is loss of habitat. The environments where these animals live are impacted by a host of hardships from siltation from construction sites, building of dams changing the dynamics of the habitat, and runoff of pollutants from the surrounding terrain, to name a few.

As many as 52 out of the 300 or so species of freshwater mussels found in North America inhabit Texas' water bodies. Texas heelsplitter, threehorn wartyback, Rio Grande monkeyface and western pimpleback epitomize some of the wacky names of these once abundant creatures. The Rio Grande monkeyface has not been seen alive in Texas since 1898. This species is presumed to be extinct. Only one mussel species in Texas is listed as federally endangered, the Ouachita rock-pocketbook. Most surviving populations of this species are restricted to Oklahoma and Arkansas. Texas has only two records and neither were found alive. In January of 2010, 15 native freshwater mussel species in Texas received a state status of threatened. Six of those 15 species are now candidates for federal listing. Those six species are: Texas hornshell, Texas fatmucket, golden orb, smooth pimpleback, Texas pimpleback, and Texas fawnsfoot. The last five of those six species can be found in the rivers and streams of Central Texas.

Texas Mussel Watch is a Texas Parks and Wildlife Department project designed to get citizens involved in collecting important data on Texas' freshwater mussels. Through attending a workshop, volunteers are placed on a Texas Mussel Watch scientific permit allowing them to legally handle animals and shells in the field. Data collected on rare species by Texas Mussel Watch volunteers goes directly into the Texas Natural Diversity Database. The Mission of the Texas Natural Diversity Database is to manage and disseminate scientific information on rare species, native plant communities, and animal aggregations for defensible, effective conservation action.

You can find more information on Texas Mussel Watch along with workshop dates and information on other Texas Nature Tracker projects at http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/tracker/.

Marsha is a Program Specialist at Texas Parks and Wildlife where she coordinates the Mussel Watch program. She works out of Austin.

The Attwater's Prairie-Chicken and the Endangered Species Act

By Mike Morrow and Terry Rossignol

Loss and fragmentation of the prairie ecosystem brought about by agricultural conversion, urban and industrial expansion, overgrazing, and invasion of prairies by woody species have been the ultimate factors influencing decline of the Attwater's prairie-chicken. It is estimated that less than 1% of the Attwater's coastal prairie ecosystem remains in relatively pristine condition. Contributors to range-wide population declines since 1987 include stochastic weather events (i.e., hurricanes, extreme drought), reduced genetic variability, parasites, disease, and red imported fire ants (Solenopsis invicta) (RIFA). All of these factors probably have contributed to reduced survival and reproductive output; however, recent research indicates that red imported fire ants have handed the Attwater's the most decisive blow, not only affecting the birds directly, but also indirectly by decimating insect numbers to the point that it has negatively impacted APC chick survival.

The APC NWR was established in 1972 under the authority of the Endangered Species Conservation Act of 1969 to protect and enhance the severely diminished prairie habitat of the Attwater's. Currently, APC NWR consists of 10,541 acres. Attwater's populations on the refuge have ranged from an estimated 25 when the refuge was established to 222 in 1987. The refuge population has declined since 1987, corresponding to range-wide population declines.

Even though recovery plans emphasized the need for habitat protection and restoration in geographically separate areas, little habitat protection or management was accomplished, other than at APC NWR, until approximately 1990, when the overall population dropped below 1,000. Since then considerable effort and funds have been spent in cooperative private-lands projects. Initially, these efforts were spearheaded by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD), with federal aid made available through Section 6 of the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Beginning in 1995, an initiative was undertaken with the primary mission of restoring native prairie grasslands within the Attwater's former range. This initiative, now known as the Coastal Prairie Conservation Initiative (CPCI), is a partnership effort involving primarily private landowners, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), Grazing Lands Conservation Initiative (GLCI), Texas Nature Conservancy (TNC), Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), TPWD and others. The bulk of funding for this effort has been provided by the USFWS and private landowners through cost-share agreements. Integral to the CPCI has been incorporation of Safe Harbor Agreements into management plans where desired by cooperators. Safe Harbor Agreements are voluntary pacts whose purpose is to promote voluntary management for listed species on private property while assuring landowners that no additional future regulatory restrictions will be imposed if listed species colonize or increase in numbers as a result of management activities. To date, more than 70,250 acres have been enrolled under Safe Harbor Agreements for Attwater's management. In addition, TPWD and NRCS landowner assistance agreements have been implemented on additional lands for the purpose of restoring the Attwater's coastal prairie habitat, including several projects initiated prior to development of Safe Harbor Agreements.

The most recent attempt at Attwater's captive breeding was initiated in 1992. Today, this captive breeding effort involves 6 institutions including Fossil Rim Wildlife Center, Houston Zoo, Abilene Zoo, San Antonio Zoo, Caldwell Zoo (Tyler, TX), and Sea World (San Antonio, TX). Numbers released each year have ranged from 35–286, averaging 131. An annual average of almost 200 birds has been released just in the last five-year period (2008-2012). Despite improving the number of birds being released in the last few years, total number of birds released annually needs to be doubled or tripled to increase the chances for establishing viable populations. An additional, dedicated breeding facility is being planned to help bolster these numbers. Annual survival estimates of released birds have been highly variable, ranging from 8–35%, averaging about 19%. Without the establishment of the captive breeding and release program, the Attwater's prairie-chicken undoubtedly would have become extinct.

The Attwater's was listed as endangered in March 1967 under the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966. An Attwater's Prairie Chicken Recovery Team was formed in 1979, and a recovery plan was approved in 1983. The Recovery Plan was revised in 1993 and 2010. Endangered Species Act listing has influenced conservation of the Attwater's and its coastal prairie ecosystem through 3 primary mechanisms: 1) making additional funding available, 2) raising awareness of its imperiled status, and 3) impacting the regulatory environment where Attwater's populations existed.

Expenditures from funds directly authorized by the ESA and its precursors include acquisition of APC NWR, which was purchased with Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) monies, and a limited amount of federal aid dollars for habitat management and research in the early to mid-1990s as authorized by ESA Section 6. In recent years, monies appropriated for endangered species management have been used primarily to fund Attwater's captive propagation and population supplementation efforts. Increased funding also has been realized from sources other than the ESA since the Attwater's has been listed, possibly due in part to the increased awareness of conservation needs resulting from listing. For example, only 3 studies were published on the Attwater's prior to its listing, compared to more than 20 after listing. Most of these studies were funded from sources other than monies appropriated for endangered species activities. Even the captive breeding program, which has been funded in part by endangered species monies and other sources, receives significant funding from participating facilities and private donations.

Unlike other endangered species, the Attwater's has generated little controversy over implementation of ESA provisions. Delays in new power- and water-line construction through Attwater's habitat necessary to minimize impacts to the bird met with some local concern, but expression of these concerns abated with the ultimate completion of these projects. This is not to say that landowners were completely at ease with the Attwater's listed status. High-profile controversies during the 1990s surrounding species such as the northern spotted owl (Strix occidentalis caurina) created an atmosphere of mistrust and concern.

Despite this diminished trust, Attwater's recovery programs continue to move forward with little contention. For example, open houses were conducted during 1997 at 3 locations within Attwater's current or former range to provide information on USFWS proposals for land acquisition and Attwater's reintroduction and to hear concerns or comments from the public. No major issues surfaced from these scoping meetings, and a program to acquire additional property for APC NWR (from willing sellers only) was implemented without incident. Twelve years later, several open house events were conducted by refuge staff to gather public input on the refuge's Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP). Once again, no major issues surfaced during these events. Another indication of the relative lack of concern over the Attwater's listed status was apparent with the CPCI. Despite the fact that priority for cost-share projects was given to properties where landowners were willing to have Attwater's released, more requests for participation in the program have been received than there were monies available to fund. Furthermore, several landowners were looking forward to future releases on their properties. However, use of Safe Harbor Agreements in conjunction with the CPCI has helped allay landowner concerns about the Attwater's listed status.

The relative lack of controversy over implementation of recovery actions for the Attwater's was attributable in part to the approach taken by those responsible for implementing those actions. Including a rancher with prairie-chickens on the Attwater's Prairie Chicken Recovery Team provided valuable insight and respectability for the team. Additionally, the general philosophy taken by biologists has been one of respect for landowners and their positions while seeking areas where both groups could work together. For example, invasion of the Attwater's prairie habitat by native and exotic brush species is a serious problem for both prairie-chickens and ranching operations. Therefore, cooperative projects often focus on managing invading brush, resulting in benefits for both the Attwater's and ranching interests.

Based on these observations, the ESA is neither a panacea nor a demon for the Attwater's, but should be viewed as a tool in species recovery. Obviously, maintaining species' populations at healthy levels is far more preferable from both biological and political perspectives. However, in the event that any species' populations decline to the point that listing becomes necessary, the ESA provides valuable resources to facilitate recovery. Further, resources and tools made available through the ESA can be used without creating a political firestorm.

Terry is Refuge Manager at Attwater Prairie Chicken National Wildlife Refuge near Eagle Lake, where Mike is a wildlife biologist.

Houston Toad Habitat Enhancement Projects in Bastrop County: 2009-2012

By Meredith Longoria

The Houston toad reached its lowest known population numbers during 2011, with a total of eight individuals detected throughout the entire season in Bastrop County. The combined impacts of prolonged extreme drought conditions, reduction in quality of habitat through land fragmentation and fire suppression, followed by the catastrophic Bastrop County Complex Fire in September of 2011, have made habitat improvement projects for this species more important than ever.

Two habitat enhancement projects utilizing LIP funding that began in 2009 were completed in 2012. Both projects included thinning of understory choked with vegetation as a result of prolonged fire suppression, and involved installment of fire breaks to facilitate prescribed burning to help maintain an open understory and prevent a build-up of fuel. Mechanical methods that limited ground disturbance were used to reduce any temporary negative impacts to the Houston toad, including the use of a hammer-flail attachment on a skid-steer loader, and/or use of a forestry mulcher. A solar-powered aerator was installed in one potential breeding pond to improve water quality for breeding Houston toads. Trees were also planted in open pasture and along potential breeding ponds to increase canopy cover where it was lacking in order to protect emerging juvenile toads during dispersal. After successful installation of fire breaks, a prescribed burn was successfully conducted on approximately 40 acres during the winter of 2012 to conclude these projects. Both sites will be monitored for vegetative response over time using photo points, as well as surveyed for Houston toad use. These two projects affected a total of approximately 400 acres of Houston toad habitat. Both landowners intend to continue with their habitat improvements through the use of prescribed fire, and/or mechanical and chemical brush treatment over time to maintain high quality Houston toad habitat.

Meredith is Diversity Biologist in Bastrop County working out of Bastrop.

The Recovery of the Brown Pelican

By Brent Ortego

Their primary food is fish and they typically catch them by plunging into the water. Views of them perched, diving into the gulf or gliding just above the waves are one of the most common wildlife scenes along the Coast. It would be unusual to find a location where they do not occur today. Few people remember when they were rare and placed on the federal endangered species list in 1973.

The recovery of the Brown Pelican population is a wildlife success story. There were about 5,000 in Texas when scientists started tracking their status in the early 1900's. The population started to decline in the 1920's when the species was persecuted for competing with commercial fishing. It declined further after World War II when the use of potent pesticides like endrin and DDT became prevalent in fighting pests in agricultural fields. [Endrin was toxic to the pelican. DDT caused eggshell thinning in pelicans and a number of avian species resulting in low production of young.] The population reached its lowest level in 1964 when there were only 50 birds reported on the Texas Coast.

The Brown Pelican was placed on the Endangered Species List in 1973, and use of pesticides was highly restricted afterwards. The population started to slowly increase.

There were only 6 nesting pairs in 1973 when the Texas Colonial Waterbird Society [A partnership between Coastal Bend Bays & Estuaries Program, National Audubon Society, Texas A&M University, Texas General Land Office, Texas Parks & Wildlife Department, and U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service] started conducting annual nest surveys. The population increased to 75 pairs in 1983, 530 pairs in 1993, and 3706 pairs in 2003. There were 3051 pairs when the species was removed from the federal threatened and endangered species list in 2009. The last nesting survey in 2012 reported 8115 nesting pairs from 11 colonies. This is a remarkable recovery from a species that went from 5,000 birds in the early 1900's to 50 birds in 1964, and then increased to over 20,000 birds today.

Major threats today are chemical spills, disturbance at nesting colonies by humans, and predation at nesting colonies by coyotes, feral hogs, fire ants and raccoons. Pelicans can be easily spooked off of nests by people making their eggs and young vulnerable to predators and the elements. Anglers and bay users are encouraged to stay at least 50 yards away from nesting islands.

I was musing the history of their populations this spring while conducting research on Padre Island National Seashore when our team observed over 4,000 Brown Pelicans flying north in one day. The Texas bays and estuaries are obviously healthy enough today to provide for a thriving population of Brown Pelicans for many years to come.

Brent is the Diversity Biologist in Region 7 working out of Victoria.

A Mystery Solved Leads to a Recovering Species

By Mark Klym

The rapid collapse of this population resulted in an equally rapid response from the birding community. By 1937, Aransas National Wildlife Refuge had been purchased, the staff of which included Robert Porter Allen, widely reputed as "the man who saved the Whooping Crane." Allen, who had previous experience working with the Roseate Spoonbill in Florida and Cuba, was hired by the National Audubon Society to spearhead a recovery effort for the Whooping Crane. He spent several summers searching for the nesting grounds for this bird, and eventually was instrumental in protecting their nesting grounds.

Allen started by following the birds north in the spring. Having monitored them through the winter, he was ready and, when the first birds took to the air, he climbed into his old station wagon and began "following" them north. His trip north was preceded by a media release, and Allen was surprised to find that, as he went north, his arrival in each community was met with someone searching him out to say "I just saw Whooping Cranes …." A good number of these were accurate reports, but the reports dropped off as he approached the Canadian border. What he was told in this area was that people were seeing these birds much farther north! Despite the common knowledge of the day that these birds nest in the grasslands of the border region between Canada and the United States, Allen took on a three year search of the northern parts of Saskatchewan and Alberta, even crossing into the Northwest Territories.

In 1954, a young forest ranger returning from firefighting in the Yukon Territory looked down as he was flying over the border between the Northwest Territories and Saskatchewan. On the shores of the pothole lakes he saw large white birds, and the mystery of where these birds nested was found. It took Allen two more summers before he was able to see these birds on their nesting grounds, but the framework was in place to protect nesting Whooping Cranes.

Listed as endangered in 1967, Whooping Cranes have seen a number of attempts to stabilize and recover their population. The down listing guidelines set out by the recovery team gives two scenarios in which this bird might be considered recovered enough that it can be removed from the Endangered Species List:

- 40 nesting pairs in the Aransas/Wood Buffalo National Park flock plus two additional flocks with at least 25 nesting pair or

- 1000 birds in the Aransas flock with at least 75 nesting pair.

The Aramsas NWR flock is doing well, and the focus has been on creating and maintaining additional flocks. These efforts have included placing Whooping Crane eggs under Sandhill Crane hens for the hens to raise, training Whooping Crane chicks to follow an ultralight plane during migration and two attempts to establish a residential flock near the southern coast within the historic range of these birds.

In 2013, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department introduced a new citizen science project with the goal of learning more about winter Whooping Cranes that were overwintering outside the traditional area immediately surrounding Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. That summer brought several Whooping Cranes spending the summer months in Texas as well - coming over from an experimental flock in Louisiana. Volunteers provide us with information our biologists could not collect on their own. To learn more about the Texas Whooper Watch please visit http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/huntwild/wild/wildlife_diversity/texas_nature_trackers/whooper-watch/.

Mark is an Information Specialist with the Wildlife Diversity Program working in Austin.

The Back Porch

By Mark Klym

That experience several years before I came to Texas almost did not happen. Threatened by habitat loss, persecution and food contamination, the Bald Eagle nearly disappeared from the lower 48 states. In 1963 counts indicated there were 487 nesting Bald Eagle pairs in the lower 48, despite the Bald Eagle and Golden Eagle Protection Act which had been in place since 1940. The continuing decline was attributed to the pesticide DDT.

An insecticide, DDT was used on crops to reduce insect damage. Animals that ate the contaminated insects were eaten by the birds, and the contamination built at each successive level. Not only were the adult birds harmed, but successive generations were harmed as many pair began producing "soft shelled" eggs that would crack during incubation or worse, would never hatch due to the contamination in the egg. In 1972, the use of DDT in the United States was banned except in certain restricted cases for public health reasons.

As early as the 1930s, people became concerned about the status of our national symbol - the Bald Eagle. The passage of the Bald Eagle Act in 1940 reduced the harassment and persecution of the bird, but it continued to decline. In 1967 the Bald Eagle was officially declared endangered in all areas of the United States south of the 40th parallel. With the passage of the Endangered Species Act in 1973, this endangered bird was afforded protection south of the 40th parallel and in 1976 it was officially listed as endangered nationwide.

That was not the end of the story however. This bird did begin to recover with the various actions taken and by 2006 the count of nesting pairs had increased to 9789 in the lower 48 states, many of those nests found right here in Texas. On June 28, 2007 the United States Department of the Interior declared the species recovered enough to remove it from the Endangered Species List entirely - something that has happened for very few species in the history of the Endangered Species Act!

Nobody likes to see an animal or plant added to the Endangered Species List - especially not the biologists and managers that work with these animals on a daily basis. Often the reason for listing is not as obvious as it was in the case of the Bald Eagle - a once plentiful bird was declining in numbers so rapidly it could not be missed. In some cases, there may be plenty of individuals where they are found, but the range may be so limited that one natural or man made disaster could wipe them out entirely. Another scenario might be that we simply do not know enough about the species, its population and its habitat needs, and so the species is proposed for listing simply to protect it from our lack of data. Other causes for listing a species might be rapidly declining or fragmenting habitat or a habitat feature that is experiencing increased or diverse pressure from development.

Whatever the cause, the most effective tool in determining whether a species should be listed, or should not be listed is a good data set that we can turn to in order to make meaningful decisions about the status of the species in question. In Texas, this data set is the Texas Natural Diversity Database, housed and maintained at Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. This database is populated from many sources, some of which are our citizen science projects, our biological assessment teams and data from our various biologists across the state obtained with permission from landowners and observations.

Another great tool in preventing the listing of a species comes with the implementation of conservation agreements in which stakeholders in the area affected by the listing agree to cooperate in identifying, protecting and enhancing critical habitat features for the benefit of the species. This has been used in a number of cases, one of the most notable being the development of cienegas in west Texas to protect desert pupfish.

Texas currently faces the potential listing of a large number of species, many of which we simply do not have the necessary data to act on. You can help by getting involved in various citizen science projects looking for and monitoring species of concern, or by simply providing data when species that we track through the TXNDD are seen.

As the sun was setting, the air came alive with the high pitched trill of toads - the Houston toad was calling again. That was several years ago too. Since then, development has moved into the area and the tank they once used is all but gone - and the night has gone silent around my home. With your help and using the tools available including the Endangered Species Act, we can keep this from happening elsewhere.

Mark is an Information Specialist working with the Texas Nature Trackers program out of our Austin headquarters.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, TX 78744

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 4200 Smith School Road, Austin, TX 78744