Background for Teachers

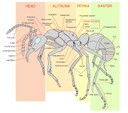

As the Student Resources Page reminds your kiddos, insects have six legs and three body sections. Since ants are insects, they too have six legs and three body sections.

Also, ants have an exoskeleton. The fact that insects have exoskeletons may be something your children do not yet know.

An ant's exoskeleton is called the "integument." An ant's integument is highly specialized depending upon the species. However, regardless of the species, it doesn't just protect the ant, but also contains organs to help eliminate waste.

Ant Anatomy:

Ant head with antennae visible. (Photo by Nick Olgeirson and www.AntWeb.org; shared thanks to Creative Commons.

- Head:

- Its head is an ant's primary means of interacting with its environment since it contains the mouth, eyes, and antennae.

Ant mandibles. (Photo by Erin Prado and www.AntWeb.org; shared thanks to Creative Commons.

- Mandibles:

- Ants have an amazing ability to alter their environments and their mandibles are the primary tool for doing so.

- Eyes:

- Ant eyes detect nearby motion, but don’t provide high resolution images.

- Antennae:

- Ant antenna are used for both smell and touch. Male and female antenna look different.

- Thorax:

- The thorax of an ant provides the insect with its mobility and is considered its "power house."

- Gaster (Abdomen):

- For species with stingers, this is where they will be located.

Ant-eresting Facts:

- Ants can carry up to 10 to 50 times their own weight!

The reason has to do with an ant’s muscle mass in relation to its body size. For a great explanation check out this site: http://www.madsci.org/posts/archives/1999-05/927263695.Gb.r.html. - Ants eat a lot of live or dead insects and nectar.

In addition, please tell your children about another important source of food for some ants: "honeydew" - a substance created by aphids. Because of this, certain species of ants (such as pyramid ants) have such a special relationship with aphids that they even help protect them from predators. - Ants usually live in the soil, but some, like carpenter ants, also live in dead wood.

Unfortunately, to carpenter ants our homes might be fair game for nest-building because they consist of dead wood – their normal habitat. - Ants take care of larvae by washing them!

This Texas Parks and Wildlife Young Naturalist mini-lesson called “Bath Time” is really interesting. We suggest reading the portion that applies to ants aloud to your students. They will really enjoy it!

http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/publications/nonpwdpubs/young_naturalist/animals/natures_bath_time/index.phtml - Ants have lived on Earth for more than 100 million years!

Check out this brief article from Harvard University:

http://www.news.harvard.edu/gazette/2006/04.13/09-ants.html - Ants create their own germ-fighters to keep the colony from getting infected.

Ants make antibiotics using a metapleural gland. This gland is unique to ants and secretes an antibiotic to prevent bacteria and fungi from invading and infecting the colony. - Ants can walk upside down because each foot has two hooked claws.

See what scientist Elizabeth Brainerd from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst found out:

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2001/09/010928071138.htm - Ants are very neat and clean. They have built-in combs for grooming their legs and antennae.

Their mouths have combs to clean their front legs and their front legs have combs to clean their back legs and antennae. - Ants do not have lungs. Instead oxygen enters and carbon dioxide exits through tiny openings on the sides of the body.

Inside, air tubes branch out to all parts of the body.

The Ant Colony

Ant colonies vary by size depending upon the species. Here in Texas we’ve got some species that create really big colonies, like leafcutting ants. Check out this article and this short video based on a 3-D journey through a leafcutting ant colony. Texas A&M University’s College of Architecture created this impressive project: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/7563372.stm.

- Worker ants:

- These sterile females also have their own divisions of labor. The smaller ones tend to be the "nurse ants" and will care for the brood, while the ones that are a bit bigger tend to have the jobs of feeding the colony, cleaning, nest building, or protection. Of course, the social structures within colonies will always vary according to species.

- Queen ants:

- It's easy to spot the queen – or queens – as she'll be many times larger than the average worker ant. Depending upon the species, some colonies will have several queens, while others will only have two. One queen can lay millions of eggs in a single lifetime. An average lifetime can range from 2-9 years.

- Brood:

- Nurse ants normally store eggs in clusters. There, eggs are kept clean using a special kind of saliva.

Next, during the larval stage, the brood becomes whitish, legless and grub-like. Eventually the larva will wind a silky thread-like substance about itself creating a cocoon.

Once this happens it becomes a pupa. Inside the cocoon metamorphosis occurs.

Eventually, the insect emerges as a fully formed adult ant. - Reproductives:

- Male ants live for only a short while, just long enough to mature and reproduce. In fact, a male ant will usually die within two weeks after mating with a queen. Female reproductives, however, will become queens themselves. Unlike males, they will eventually lose their wings.

Lifecycle in Colony:

- STEP 1: Queen breaks off wings and lays eggs that become female workers , which can’t reproduce.

- STEP 2: Then queen lays eggs and workers feed her.

- STEP 3: New eggs become more workers, winged males or a few winged females that will leave the nest (reproductives).

- STEP 4: Workers tend brood; reproductives mate. Male reproductives die. Female reproductives become queens and leave the nest to establish their own colonies.

- STEP 5: Cycle starts over.

Ant Communication

Before you read on, we suggest taking about three minutes to listen to renowned biologist E.O. Wilson briefly discuss the role pheromones play in ant communication in this episode of "Pulse of the Planet" created by the National Science Foundation:

http://www.pulseplanet.com/dailyprogram/dailies.php?POP=2800.

Pheromones are the "chemical words" we've referred to in the Student Research Pages. As Wilson indicates, ants utilize different pheromones depending upon the message they desire to convey. The antennae are the principle means of receiving these messages.

Another short resource we recommend for understanding ant communication is this 3 minute video that helps explain how the social stomach works:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5CAjWaZx2Ks&feature=player_embedded

Ants have social stomachs in which they store liquid food in an expandable pouch called a "crop." The liquid food can be used to leave a chemical trail – those pheromones Wilson referenced – or it can be used to bring food back to the colony to share. Ants regurgitate from the crop when needed to feed nest mates that can’t leave to acquire their own food – i.e. nurse ants or even the queen. One ant induces another to provide liquid food by touching the other ant’s head with its foreleg.

Ants don't just use pheromones, or chemicals, to communicate. Using a type of communication called "stridulation" the insects create a high-pitched sound by rubbing a thin scraper on their waist against a ridge on their abdomen. The sound is barely audible to humans.

Ants use their legs quite a lot to detect sound. There they have special organs that work almost like sonar.

Native vs. Invasive Ants

Texas A&M University’s Imported Fire Ant Research and Management Project has created a very good resource to help you understand the GENERAL CONCEPT of NATIVE vs. INVASIVE SPECIES. Check it out: http://fireant.tamu.edu/materials/factsheets_pubs/pdf/texas1.pdf.

For the sake of the kiddos, we used the simplified definition below on the Student Research Page:

Native Species = ants originally from Texas; ants that naturally occur here

More technically, a native species is one that occurs naturally with respect to a particular ecosystem, rather than by accident or deliberate introduction.

For the sake of the kiddos, we used the simplified definition below on the Student Research Page:

Invasive Species = ants NOT originally from Texas

Invasive species came to live here from someplace else.

They shouldn’t live here because they make life difficult for the native Texas ants that didn’t evolve to compete with them.

But, in more technical terms, we’ll use the definition supplied by Texas A&M University’s Imported Fire Ant Research and Management Project

(http://fireant.tamu.edu/materials/factsheets_pubs/pdf/texas1.pdf):

"As legally defined, an invasive species is 'An alien species whose introduction does or is likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human health.'"

Under that definition, we can certainly see how red imported fire ants qualify as invasive.

RED IMPORTED FIRE ANTS

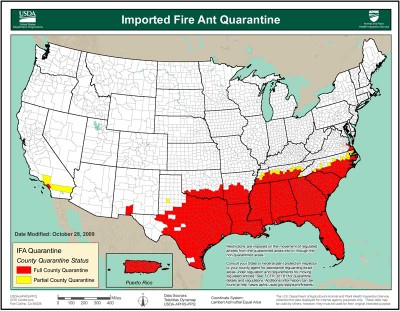

Red fire ants were introduced to the United States in the thirties by way of cargo ships that landed in the Gulf Coast (probably Mobile, Alabama). Originally from South America, ironically, that continent only has about 20% of the quantity of fire ants that we do here. Why? Because red imported fire ants in the United States have no natural predators, whereas in South America, where they evolved in their native environment to compete against other native species, they do.

Unfortunately, red imported fire ants can be found throughout Texas. Figures from the early 2000s indicate 56 million acres in the state were inhabited by the invasive species. Today, they can be found regularly in nine states throughout the south and it’s estimated that their range now covers over 260 million acres. Recently they were even found in California.

The good news, if you can call it that, is that the problem should be contained primarily to the southern portion of the U.S. because the ants cannot tolerate freezing temperatures for extended periods of time. That seems to be their one weakness as even most pesticides have little long-term effects over their continued growth.

Some of Texas’ native ants are our best line of defense against red imported fire ants, so be VERY careful about which ants you kill. These native ants could turn out to be your best friends:

BE EXTRA CAREFUL WITH THESE EXTRA GOOD GUYS:

- Pyramid ants – are known to be red imported fire ant enemies

- Bigheaded ants – will especially seek out and destroy red imported fire ant queens

- Black crazy ants – they’ll also destroy fire ant queens

CHECK IT OUT!

- FIRE ANTS:

- Texas A&M University has an Imported Fire Ant Research and Management Project full of really good information. http://fireant.tamu.edu/.

- RAHSBERRY ANTS:

- ** VIDEO: See this "Texas Country Reporter" video about Rasberry crazy ants, featuring Tom Rasberry, the man who discovered these invasive ants: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NgpCXGsC6PU.

- RASBERRY ANTS:

- This article by Sheryl Smith-Rodgers in Texas Parks and Wildlife Magazine discusses the Rasberry crazy ant problem in more detail: http://www.tpwmagazine.com/archive/2009/apr/scout6/.

Ants, Animals & Us

Kids probably don’t need much convincing when it comes to telling them about the "cons" of ants, so instead concentrate on the positive roles ants play. And there are PLENTY!

In fact, ants play such an important role on making Earth’s ecosystems function that things just might shut down without them. Seriously! Because of their huge ecological footprint, these tiny creatures help keep nature’s wheels turning.

Ants have a huge ecological footprint!

There are an estimated 10,000 trillion - yes, you read that right – 10,000 TRILLION – individual ants alive at any one time all doing what ants do. These 10,000 trillion individuals belong to an estimated 14,000 species and subspecies of ants worldwide.

That many critters means ants contribute plenty of "biomass." Ecological studies often use biomass to indicate an organism’s importance in ecosystems. (Biomass isn’t the only indicator, but it’s a biggy.)

Discuss these big five "Ant Ecological Footprints" with your students:

- 1. Ants help with pollination.

- When ants crawl from one nectar-laden flower to another they often take along pollen for the ride.

- 2. Ants help reduce diseases by eating dead stuff.

- Often, ants are referred to as the janitors of the world because they’re a major part of Earth’s clean-up crew.

- 3. Ants help disperse seeds.

- In many ecosystems, ants are important dispersers of seeds. In desert regions they’re one of the principle consumers of seeds.

- 4. Ants play a huge role in the food chain.

- These protein-rich insects provide meals for a myriad of animals. Ants sustain many lives with their own lives – from other insects, to birds, mammals, reptiles, even to providing food for some humans.

- 5. Ants significantly contribute to the health of Earth’s soil

- By helping to recycle nutrients back into the soil by cutting up leaves and twigs and bringing them below ground to aerating the soil, ants significantly increase soil fertility. Of course, different species make varying degrees of contributions, but overall ants profoundly affect the health of Earth’s soil.

CONS:

Most of the ant "cons" have to do with the collision of the human and the ant worlds.

When that happens it could increase the chance of being bitten or stung by an ant – a definite “con.” And, when ants live where we do (i.e. – in our homes) they’re usually considered pests. They may consume resources we want (our cupcakes!) or need (our corn crops!) or destroy resources we use (the wiring for our computer!). For example, carpenter ants might consider the dead wood of our houses good places to nest, especially when the wood is damp.