Background for Teachers

Vaqueros:

Vaqueros drove cattle long before cowboys, back in the days when Texas belonged to Spain. One of their main paths took them back and forth between what we now call south Texas and Mexico City. Even though it was tough work, to be a vaquero carried quite the mark of pride. Over a century before the cowboy arrived on the scene, vaqueros took the first steps to tame the Wild West. Since the late 1500's, before the Pilgrims even landed on Plymouth Rock, vaqueros were already rounding up the Longhorn cattle that roamed free in the brush country. They'd bring these cattle to markets in Mexico or tend to them on ranches. Since ranches were located mostly on Spanish missions and presidios so too were the vaqueros in those earliest days.

According to photographer Kendall Nelson, author of Gathering Remnants: A Tribute to the Working Cowboy, about one out of every three working "cowboys" in the mid-1800's was a vaquero. Nelson's site contains some really interesting information and photographs:

http://www.gatheringremnants.com/BookMain.aspx.

The vaquero culture still thrives in Texas. You'll find the word "charro" often used to refer to the men who do vaquero work. Check out this article in the Houston Chronicle that discusses how modern-day charros work to keep vaquero traditions alive:

http://www.chron.com/disp/story.mpl/ae/music/jump/3081434.html.

Vaqueros' traditions keep going in Texas through "charreadas," the vaquero's equivalent to the cowboy's rodeo. This competitive event, originally developed in Mexico, celebrates the practices of the men who work cattle and horses for a living. Today, a modern charreada consists of nine events and you'll find women as well as men competing.

This PDF provides extremely detailed drawings of vaquero attire, his tools, and the gear he used for his horse. An excellent source of reference!

http://www.parks.ca.gov/pages/485/files/vaquero%20revised%203-13-12.pdf

Adorned in traditional garb, these women ride horseback to announce the start of the charreada festivities.

Cowboys:

Cowboys usually found themselves hitting the road come spring when most cattle drives began. That's when grass became available for herds to eat along the way as they traveled. Leaving Texas in the spring also gave cowboys enough time to get the herds up north before winter came.

Amazingly, it took only about twelve to fifteen men to manage a herd of about 3,000 cattle! These men were overseen by the trail boss, who was a lot like a captain of a ship in that he had ultimate authority over the all the workings of the cattle drive.

Some considered the cook the next most important person on the crew. And, even though his primary responsibility was to prepare the meals, he did help herd when needed. The rest of the crew either worked as "wranglers" or "drovers." Wranglers took care of any horses not being ridden (sometimes even wild mustangs being brought to market). Drovers rode in appointed places to help drive cattle.

Check out this excellent clip from the DVD, "Gathering Remnants: A Tribute to the Working Cowboy," by Kendall Nelson: http://www.gatheringremnants.com/DVDTrailer.aspx. It may not hold the attention of your children, but you will certainly enjoy it!

Cattle Drives:

Even though the era of the great Texas cattle drives only lasted roughly twenty years, this period of our state’s history really captures the spirit of the Old West. From about 1865 until roughly the mid-1890's, vaqueros and cowboys brought an estimated five million cattle to markets up north where they were either sold or caught a ride on railroads to markets elsewhere. These men also drove additional numbers of cattle to markets out west.

The era came to an end by the mid-1890's. By then railroads had brought the markets to Texas and barbwire had helped fence in much of the open range land that once made driving cattle possible.

Cattle drive included animals owned by several different ranchers all driven together in what was called a "trail herd." The trail boss kept paperwork listing brands or earmarks designating who owned which cattle. In addition, all of the cattle of the "trail herd" received an identical brand as well to mark them as part of the drive. This was called a "road brand."

The Chisholm Trail

Jesse Chisholm created the famous "Chisholm Trail" in 1865 and the first cattle drives along his trail set out for the north from DeWitt County in 1866. That's pretty close to San Antonio.

It's important to note that Chisholm established the basis of the Chisholm Trail, but other drovers expanded it both to the north and south. It was common for trails to morph thusly with use. In fact, trails could originate where herds were created and end up where a market was found. In fact, there were hundreds of smaller trails leading to the major trails that ran through Texas.

That said, by the time it was at its peak in the early 1870’s, the basic route of the Chisholm Trail went from the Rio Grande near Brownsville through Cameron, Willacy, Kleberg, Nueces, San Patricio, Bee, Karnes, Wilson, Guadalupe, Hays, Travis, Williamson, Bell, McLennan, Bosque, Hill, Johnson, Tarrant, Wise and Montague counties. It crossed the Red River and continued to Dodge City and Abilene, Kans. Another popular route approximately paralleled the main trail, but lay farther east.

The Chisholm Trail crossed the Colorado River near Austin, Brushy Creek near Round Rock, Kimball's Bend on the Brazos River, and the Trinity Ford in Fort Worth below the junction of the Clear and West forks.

The Chisholm Trail hit its peak use in 1871. By 1884, interstate railroads firmly established themselves in Texas and it was no longer necessary to drive cattle to northern markets. As a result, by the mid-1880's, the Chisholm Trail was virtually out of use.

The Goodnight-Loving Trail

In west Texas, the Goodnight-Loving Trail became the first of the major post-Civil-War trails thanks to Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving.

This view from a stereoscopic card shows the ranching terrain in Palo Pinto County where Goodnight began his ranching operations.

First, however, Goodnight established his own herd of cattle in Palo Pinto County in the northern part of the state in the late 1850s.

After spending time in the military during the Civil War, Goodnight decided to round up his cattle and herd them for the mining regions of the Rocky Mountains. In order to avoid Indians, he planned to use an old Butterfield Stagecoach route to the southwest, which followed the Pecos River upstream and then went northward toward Colorado.

As he prepared for his journey, he met up with Oliver Loving, who also wished to move a herd of his own. The two men decided to make the journey together, setting off on June 6, 1866 with about 2,000 head of cattle.

They departed about 25 miles southwest of Belknap and followed a route that took them past Camp Cooper, by the ruins of old Fort Phantom Hill, through Buffalo Gap, past Chadbourne, and across the North Concho River, which is twenty miles above San Angelo. Along the way, they crossed the Middle Concho then followed it west to the Llano Estacado. They crossed into New Mexico and finally into Denver.

Their journey gave birth to the Goodnight-Loving Trail.

The two men took this route several times until Loving's death in September 1869 when they were attacked by Indians in New Mexico. Moments before his death, Loving exacted a promise from Goodnight that he would bury Loving in his home cemetery in Weatherford, Texas. Thus, if you’ve ever read Larry McMurtry’s book Lonesome Dove, you'll understand the reference to Goodnight and Loving as "The Original Lonesome Dove."

Want to learn more about the cattle trails of Texas? Check out the Texas State Historical Association’s Handbook of Texas Online. They’ve got a great piece called, Cattle Trailing at:

http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/ayc01

Stampedes

Stampedes probably presented the biggest consistent danger to cowboys and vaqueros herding cattle. Longhorns had the reputation of startling easily. A rustle in the wind, the sun reflecting just so off a metal canteen, lightning - just about any noise, sight, or smell could spook these cattle into a dangerous stampede.

Drovers employed a trick to stop stampedes whereby they got in front of the herd and turned them to the right, driving them into a circle. This forced the rest of the herd into a circle, which the other cowboys would work into a tighter and tighter ball as the rest of the herd approached. Ultimately, the goal was to have the entire herd moving in a smaller and smaller circle until all the cattle were gathered so tightly together that only a very slow (and thus, sedate) circular movement was possible.

The singing cowboy, though much different in reality than Hollywood's portrayal of him, did, indeed play a role in trail-drive culture and one that went beyond simply fireside entertainment. His singing helped keep stampede-prone herds calm in touchy situations.

Longhorns

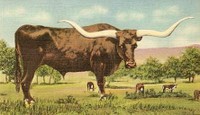

Cattle have played a big role in Texas history since the 1500’s when Spaniards arrived with domesticated cattle, which they set loose in south Texas. Descendants of these cattle came to be called "longhorns" because the spread of their horns could reach up to eight feet!

You can see from this 1908 postcard how the longhorn holds a certain mythological status in Texas, likely due to the important role it's played in helping to secure the Lone Star's reputation as a place of daring and independent spirits.

While the role of cattle grew during the time of the Texas Republic and its days of early statehood, it remained a relatively small industry until after the Civil War when nation-wide demand for beef created strong demand for Texas longhorns.

The demand, ultimately, was so strong that by the mid-1930's it looked as though Texas might lose its remaining longhorn. In 1936, Fort Worth businessman Sid Richardson proposed the creation of an official state herd. Working in conjunction with Texas historian, J. Frank Dobie, and cattle rancher, Graves Peeler, Richardson assembled a herd of twenty longhorn from south Texas.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department agreed to provide an original home for the state herd at Lake Corpus Christi State Park. Dobie and Peeler then went to work attempting find more longhorn. These they placed at Brownsville State Park. By 1948, all longhorns had been rounded up. That same year, they relocated relocated twenty-one of them to Fort Griffin State Park and established a final home for the Official State of Texas Longhorn Herd.

Today, the herd's ancestors live at Fort Griffin where breeding efforts and all official herd business gets conducted. However, other state parks also host herds created from those same ancestors.

Brands

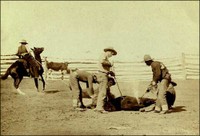

This photo from 1888 shows cowboys branding a cow. One brand is probably the brand of the owner. The other brand the calf is receiving is likely the road brand designating it as part of a trail herd.

Of course, ranchers still use brands and ear tags today to identify cattle as their own, but before fencing became commonplace in the 1870's, brands proved especially helpful for indicating who owned which cows. And, once beef prices soared, you definitely wanted no confusion about who owned what – those sources of beef brought in plenty of cash!

Like many of our other ranching practices, the Spanish brought the practice of branding to North America. When Texas belonged to Spain, brands and earmarks were recorded in ledger books maintained by Spanish officials at the provincial government offices located in San Antonio.

A cattle drive included animals owned by several different ranchers all driven together in what was called a "trail herd" and had to be identified as belonging to the same cattle drive. Thus, all of the cattle of the "trail herd" receive an identical brand in addition to the brand designating who owned them. That second brand was called a "road brand."

Ranching

You can help your students understand that cowboys, while an independent breed, needed to be hired by someone or they wouldn't be able to make a living. Most cowboys and vaqueros worked for ranches when they weren't herding cattle.

While Texas still has thousands of ranches today, two ranches in particular played an important part of Texas' history, The King Ranch and the X.I.T. Interestingly, these were located on opposite ends of the state: the King Ranch is located in south Texas, while the X.I.T. was in the Panhandle, running all the way to the Oklahoma border.

The King Ranch

The King Ranch still operates today. In fact, it's known as the biggest cattle ranch in the world. Read the history of the King Ranch on their website at:

http://king-ranch.com/about-us/history/.

The vaqueros who work there today still have a special name: "Kineños."

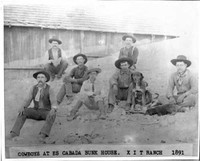

This photo is also on the Student Research Page. We suggest discussing why the cowboys in the photo aren’t smiling. Why weren’t they? The children might say that it's because the cowboys were unhappy. Perhaps, because the more likely reason was that in the 1890’s, a camera’s shutter had to remain open for several minutes causing subjects to stay still while the image was created. Since it was easier to maintain serious expressions than smiles, serious expressions became commonplace in photos from this era.

The X.I.T. Ranch

Charles B. and John V. Farwell ended up with 3,000,000 of Panhandle land when they agreed to build the new Texas capitol down in Austin in exchange. Learn the details at "The Handbook of Texas Online":

http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/apx01.

The last parcel of X.I.T. was sold off in 1963 and the ranch no longer operates today, however, it truly was a significant part of Texas ranching history.