Clear Creek Gambusia (Gambusia heterochir)

TPWD © Glen Mills. Educational use permitted.

- Texas Status

- Endangered

- U.S. Status

- Endangered, Listed in 1967

- Description

- Clear Creek gambusia grow to about one inch in length.

- Life History

- It feeds on small invertebrates. This fish is found in areas with coontail, an aquatic plant, and Hyalella texana, an endemic amphipod (small crustacean). The coontail provides habitat for the amphipod, which in turn serves as the main food of the Clear Creek Gambusia. The submerged aquatic plants provide protective cover from predators such as bass and sunfish, and provide habitat for the small animals eaten by this fish. Young are born live. Clear Creek gambusia produce several broods of young from March through September.

- Habitat

- This species lives in clear, slightly acidic spring water of constant temperature, with abundant aquatic vegetation.

- Distribution

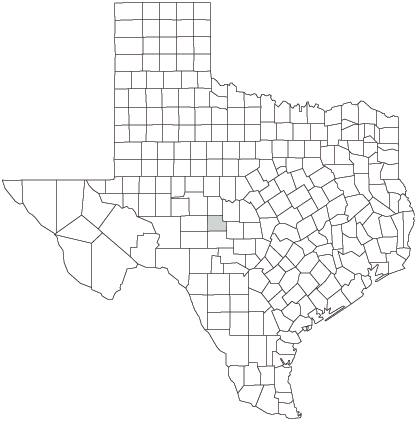

First discovered in 1953, the Clear Creek Gambusia exists only in the springfed headwaters of Clear Creek, a tributary of the San Saba River in Menard County.

First discovered in 1953, the Clear Creek Gambusia exists only in the springfed headwaters of Clear Creek, a tributary of the San Saba River in Menard County. - Threats and Reasons for Decline

Originally, Clear Creek was a clear springrun that flowed freely for about 3 miles to its confluence with the San Saba River. Most or all of the creek was probably inhabited by springrun species such as the Clear Creek gambusia and associated plants and animals. A series of dams, the first one built in the 1880s and the others during the 1930s, were constructed to provide irrigation to cultivated fields. The resulting changes in habitat encouraged population buildup of plants and animals more tolerant of variable water temperatures. These eurythermal (wide temperature tolerance) organisms soon overwhelmed the springrun animals that were not isolated upstream from the first dam (Dam 1).

Since the only habitat for the Clear Creek gambusia exists upstream from Dam 1, this dam is vital for protecting an environment isolated from invasion by the western mosquitofish. In 1979, Dam 1 was in serious disrepair due to age, the effects of tunneling by nutria (a large introduced rodent), and the expansion of root systems of trees. Hybridization between the Clear Creek gambusia and western mosquitofish had occurred in the vicinity of the dam. This hybridization problem was theresult of mosquitofish juvenile females moving to the upper pool through damaged portions of the dam. If allowed to continue, hybridization and competition from the western mosquitofish may have eliminated the Clear Creek gambusia. In the summer of 1979, Dam 1 was rebuilt, securing the upper pool habitat for the Clear Creek gambusia.

In 1985, researchers found an increased number of Clear Creek gambusia downstream from the reconstructed dam. Soon after the damwas rebuilt, rainwater killifish (Lucania parva) were found in Clear Creek below the dam. This fish is not native to the Edwards Plateau and may have been released into Clear Creek by someone discarding leftover bait. Rainwater killifish and western mosquitofish, although not closely related, are very similar with respect to food habits, habitat preferences, and tendency to move seasonally to areas of warmer water. Thus, rainwater killifish compete directly with western mosquitofish. Reduction in the numbers of western mosquitofish apparently allowed the Clear Creek gambusia to survive in greater numbers below the upper dam.

Finally, the continued existence of the Clear Creek gambusia depends on continued flow of Wilkinson Springs. Protection of the Edwards- Trinity recharge zone is essential. Any changes which reduce water flow or deteriorate water quality in Wilkinson Springs could have disastrous consequences for the Clear Creek gambusia.

- Ongoing Recovery

- Continuous monitoring is ongoing to detect factors that may affect the Clear Creek gambusia population and determine the current genetic status of the population. The owners of Wilkinson Springs have been instrumental in protecting the species' habitat. Providing information to landowners and the general public concerning habitat requirements for rare and endangered fishes is an important part of the recovery process.

- How You Can Help

Area landowners can help by protecting the groundwater of the Edwards- Trinity Aquifer. Do what you can as an individual to conserve water and prevent pollutants from entering the aquifer. Care should be taken to avoid reduction in recharge to the aquifer. Limestone aquifers are vulnerable to pollution and measures to prevent aquifer contamination are urged. Land managers can help by implementing sound range management practices designed to protect vegetative cover, improve range condition, and prevent soil erosion and runoff. Good vegetation management will help to ensure optimum aquifer recharge and the continuous flow of Wilkinson Springs and others like it.

Since competition and/or hybridization with closely related or introduced species is a major threat to endangered fishes, never release fish into natural waters from which they didn't originate. Although an exception occurred in the case of the rainwater killifish at Clear Creek, beneficial impacts resulting from introductions of exotic species are the exception and not the rule.

Finally, you can support the Special Nongame and Endangered Species Conservation Fund by purchasing a stamp, available at the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) headquarters in Austin or at most State Parks. Part of the proceeds from the sale of these items is used to conserve habitat and provide information concerning rare and endangered species.