Bumble Bee Life-Cycle

Of the hundreds of bee species native to Texas, bumble bees are among the most familiar. Only a handful of bees are as large as bumble bees and few are as hairy. Their fuzzy black and yellow bodies are easy to recognize as they buzz from flower to flower. Over 50 species of bumble bee occur across North America. A total of nine bumble bees have been documented from Texas. Bumble bee diversity in Texas is highest in the eastern half of the state and declines as you move westward into the Chihuahuan Desert.

Colony Life

Bumble bees, with a few exceptions, are social insects with individual queens founding colonies composed of daughter workers and developing offspring. Bumble bee colonies in North America north of Mexico persist for just under one year, in contrast to the colonies of honey bees that can persist for several years. Bumble bee colonies start anew each spring with queens that hibernated over winter. When queens emerge with the arrival of warm weather, they must feed and find a suitable place to establish a nest.

Brown-belted bumble bee feeding on early spring flowers. Courtesy of Jessica Womack.

Having spent the winter living off stored fat, bumble bee queens feed heavily from early spring flowers. Bumble bees nest in or on the ground, taking up residence in protected spots such as under grass thatch or in abandoned rodent burrows. Compost piles, abandoned birdhouses, and brush piles may even be co-opted by bumble bee queens as nest sites.

After a suitable site is found, the queen provisions it with nectar and pollen. Bumble bees can secrete wax and the queen uses this material to create receptacles (nectar pots, pollen cells) to store food. With enough nectar and pollen amassed, she will lay her first batch of eggs which will all develop into daughter workers. The queen stays close to her eggs, warming them by vibrating her flight muscles. The larvae that hatch from the eggs feed on pollen supplied by the queen. After enough larvae develop into adults, the queen no longer leaves the nest to forage but instead focuses on laying eggs to expand the colony. Daughter workers take over nectar and pollen foraging, care of larvae, and nest maintenance. Worker bumble bees will also defend their colonies by stinging if harassed.

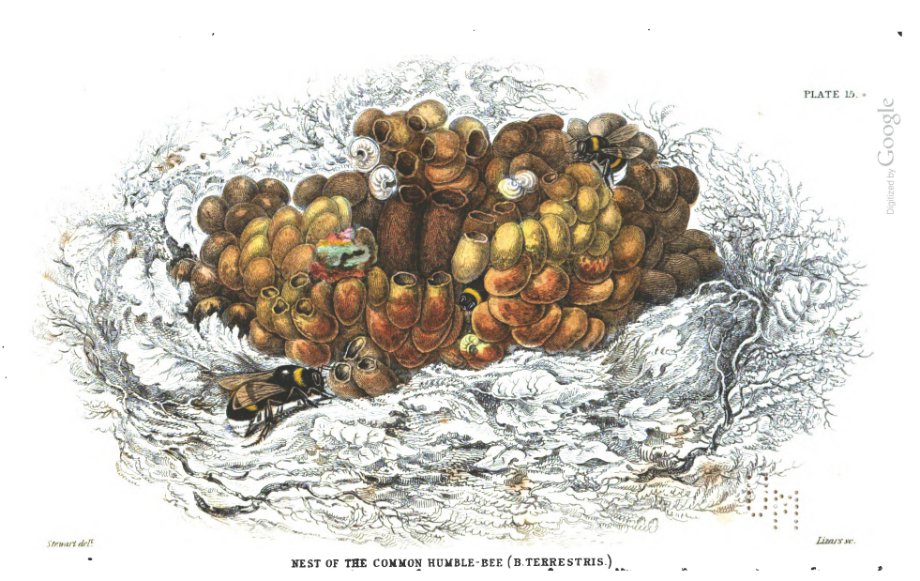

Illustration of a bumble bee nest with wax cocoons and nectar pots.

From spring into early summer, the queen will continue to lay eggs and the colony will grow in size given sufficient food resources. Bumble bees do not store great quantities of nectar and pollen, only enough to sustain the colony for a few days, much unlike honey bees. Consequently, bumble bee colonies are very much dependent upon access to a succession of flowering plants from spring into fall to complete colony development. Flower-rich grasslands are optimal habitat for bumble bees providing both food sources and nest sites. By mid-summer, a bumble bee colony with access to good sources of nectar and pollen may reach a population of 300-600 workers.

Foraging American bumble bee carrying pollen. Courtesy of Jessica Womack.

New queens, and the colonies first male bumble bees, are generally produced over a discrete period during mid- to late summer. Eggs that will develop into new daughter queens are generally laid by a colony's queen when her workforce of daughter workers reaches a sufficient size. Only those colonies with large numbers of workers are capable of producing queens as those larvae are fed much more food over a longer period of time than daughter worker or male bumble bee larvae. Adult queen bumble bees are often two to three times the size of worker and male bumble bees.

For a colony to produce queens, it must contain enough foraging workers to meet the increased demands for food. To reach a size sufficient to produce new queens, colonies require a near-continuous supply of nectar and pollen from early spring into late summer. Queens of colonies with small contingents of daughter workers will often produce only males and no queens at all. Areas that host few flowering plant resources often produce very few queens which can lead to decreased bumble bee abundance, increased likelihood of inbreeding depression, and reduced genetic variability.

Male American bumble bee feeding on nectar. Courtesy of Jessica Womack.

Male bumble bee larvae are fed less food than queens and develop quickly into adults. Once they reach adulthood they soon leave the nest, never to return. Males spend their days feeding on nectar and establishing territories to attract new queens after they emerge from the nest. When new queen bumblebees leave the nest, multiple males vie for mating opportunities. Following mating, these new queens spend considerable time through the remainder of the summer and into the early fall feeding from flowers to build up the fat reserves needed for overwintering.

As fall progresses, temperatures continue to drop and flowers dwindle, the old queen and all her daughter workers slowly decline and the entire colony perishes. Males, likewise, die. The only bumble bees to survive are the new queen bumble bees that search out some protected spot to shelter themselves from the elements. There they overwinter and wait for the return of spring and the chance to establish their own colonies the following spring.