Genetic and Environmental Interaction in White-tailed Deer: 1992-1999

(41 Sires, 137 Dams, 217 Yearling Antler Sets)The information presented on this page is published in Understanding Spike Buck Harvest

(PDF 2 MB) (by Bill Armstrong, Kerr Wildlife Management Area, TPWD).

(PDF 2 MB) (by Bill Armstrong, Kerr Wildlife Management Area, TPWD).

Background

Since 1983, wildlife biologists with Texas Parks and Wildlife Department have been collecting white-tailed deer age, weight, and antler data from hunter harvested deer throughout the Edwards Plateau. Analysis of this data has demonstrated that in years with good nutritional range conditions, fewer spikes were in the harvest. It also indicated those years in which range conditions were poor, there were more spikes in the harvest. Range nutrition was affecting antler production. However, this same data also indicated that even under poor range conditions, there were some deer that produced good antlers. It also demonstrated that under good range conditions, there were always some spike-antlered deer. Therefore, it was reasoned that there were three types of yearling deer on the range: (1) deer that always produced fork antlers even under adverse conditions, (2) deer that always produced poor antlers even under good conditions, and (3) deer that in good years produced forked-antlers and in poor years produced spike-antlers. Biologists named this third group of deer, "swing deer." From a management point of view, swing deer slow management gains because poor genetic traits are masked in good years. Researchers reasoned that if there was a genetic basis for these deer, then the frequency of "swing deer" in a population could be reduced through a selection program and more rapid antler improvement would result. A study, Genetic/ Environmental Interaction in White-tailed Deer, was initiated to see if swing deer could be reduced or eliminated from a population.

Overview

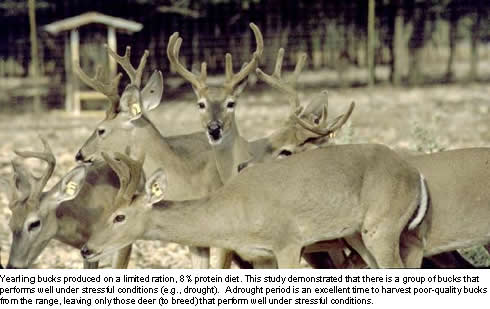

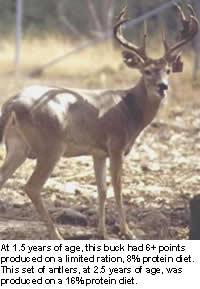

In this study, fawns were weaned in October and were placed on an 8% protein ration and their daily intake also was highly restricted (approximately 1/2 normal intake) to simulate drought effects. The deer were raised on this limited ration until they completed their antler growth the following October. They were then placed on a 16% ad lib ration and their antler production will be monitored until they were four years old. The five yearlings that exhibited the best antler growth each year on this limited diet were used as brood bucks and bred to unrelated does. Only yearling bucks were used as brood bucks. Their offspring were weaned in October and placed on the limited ration. This process was repeated yearly in order to make more rapid genetic gain. Also, if a yearling buck was a spike, the related female offspring were removed from the breeding herd if the females had also produced another spike from another buck. (In other words, two spikes and you're out). This had the effect of ensuring that "swing deer genes" were not maintained in the herd and more rapid gain could be made. The yearling breeding trails were completed in 2000. The fawns born in 1999 will be monitored until 2003, when they will be four years of age.

Data from this study indicate that there is a genetic/nutritional interaction that governs "swing deer." They also suggest the best time to harvest spikes and make genetic gain is during droughts or other periods of nutritional stress. One of the best times to harvest swing deer is when starting a habitat management program on unmanaged ranches when deer numbers may be excessive and herd reduction is needed to improve habitat. Giving priority to removal of spike-antlered deer during that time will help accelerate gains.