Sleep and Hibernation

Food, water, and shelter always top the list when we think about the things most important to our well-being. We often seem to forget something that is absolutely essential—sleep. A lack of sleep disturbs the mental processes. The person deprived of sleep loses energy, becomes irritable, has difficulty concentrating, makes numerous mistakes with routine tasks, hallucinates, and will doze off if not kept active.

When we go to sleep, our muscles relax, our heartbeat and breathing rate slow down slightly, and our body temperature drops a couple of degrees. Measurable changes also occur in the brain-wave patterns. Sleep is defined as the “natural periodic suspension of consciousness during which the powers of the body are restored.”

The amount of sleep required daily varies with age and the individual. Newborn babies may need as many as twenty-two hours, while their grandparents often sleep only five or six. Men generally need more sleep than women, but the average human spends seven to nine hours sleeping—about one-third of his or her life.

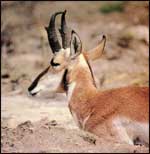

Hoofed mmals, such as this antelope, are among the short sleepers. They can sleep standing up or bedded down on the ground. While they sleep or nap, their ears and noses remain active to warn them of any danger.

Sleep in wildlife is even more varied. Both long and short sleepers can be found among mammals, birds, and reptiles. As a general rule, animals that sleep the most are more secretive creatures with protective dens, burrows, or caves, or they are predators with few enemies. Prey species, which must be alert for predators, get by on less.

Bats are real sleepyheads, averaging about twenty hours a day. Safe and secure in their dark caves, they sleep away the daylight hours and then usually take another nap on a convenient roost outside the cave between their two nightly feeding periods. A close runner-up to the bat is the opossum. Snuggled into a hollow tree, woodpile, rocky crevice, or abandoned underground burrow, the opossum may not stir all day. Venturing forth to feed shortly after dark, this marsupial (pouched animal) may have slept as many as nineteen hours.

Members of the cat family can fall asleep anytime during the day or night. Easily awakened, they appear to take only short catnaps, but these predators actually manage to sleep some sixteen hours a day—twice as much as a human. They have few enemies to bother them while they are asleep, and they manage to be very active in the few hours they are awake.

The dog family, which includes the elusive coyote, may snooze twelve to fourteen hours a day. Dogs, like all other mammals, dream while they are asleep. What they dream is anyone’s guess, but they often show responses to the dreams. You probably have heard one yelp or whine and perhaps have noticed its muscles and legs jerk and twitch during sleep.

As one of the main prey species for many different animals, rabbits must be extremely alert to their surroundings both day and night. Therefore, it is not surprising that they sleep very little, relying on short, dozing naps for their required rest. They may manage as many as twenty of these light naps in a single day.

Hoofed mammals, such as deer and antelope, also are among the short sleepers. During the day they may take brief naps while standing, but they continue to open their eyes occasionally to look around for danger. Their noses and ears remain active when they bed down on the ground to sleep. Any sign of danger immediately awakens them for flight. These mammals usually sleep about four hours a day, but they can get by on less. An interesting fact researchers have discovered about cattle, which also are hoofed mammals, is that although they can sleep standing up, they dream only while lying down. Perhaps the same is true for wild hoofed mammals such as deer.

Bottle-nosed dolphins sleep during the night, floating about a foot under the water with their tails dangling down. Every half-minute or so a few slow strokes of the tail bring the dolphin’s head to the surface so this marine mammal can breathe. Its eyes seldom remain closed for longer than thirty seconds when it sleep.

Most birds sleep when the sun goes down. They perch securely on a branch with their beaks tucked into their feathers and await the dawn. Their body design makes it impossible for them to fall off their perch while they are asleep. All of the bird’s toes are connected to a main tendon that runs up the foot, bends behind the ankle and passes in front of the knee. When the bird stands, the tendon is loose and the toes are relaxed. However, when the bird settles into a sitting position, the tendon stretches tightly, pulling the toes into a curled position around the branch. The bird cannot uncurl its toes until it stands up.

The hummingbird stays busy, dining fifty or sixty times a day to provide energy for a body power plant that must be refueled every ten to fifteen minutes. Its only rest comes at night when it sleeps. Lacking the energy reserves needed to stretch through the night, the hummingbird passes into a condition bordering on suspended animation. While it is in this state, called torpor, its body temperature drops, and its energy output is reduced to one-twentieth of that which would be used during normal sleep. Although most animals cannot be awakened from torpor quickly, the hummingbird’s arousal is almost instantaneous.

Owls, recognized as highly efficient night predators, spend the major portion of the daylight hours sleeping. Since a sleep-dulled owl would be easy prey for a daytime predator, the owl must choose its sleeping place carefully. Attics, rock crevices, hunters’ deer blinds, and shaded, leafy trees provide sheltered roosts where the bird can safely tuck its head into its feathers and dream the day away. On dreary, cloudy days when the sun is hidden from view, the owl may spend part of its sleeping time hunting for food.

Some birds gather together for mutual warmth or protection. A sudden dip in temperature may cause several small cavity-nesting birds to snuggle in one nest. On one occasion when unseasonably low temperatures occurred, a birder discovered more than twenty dead bluebirds huddled in one nesting hole. Their combined warmth was not enough. Quail sleep in a circle on the ground with their tails pointing toward the center, and cold winter nights find goldeneye ducks sleeping together in tight, floating bunches. Ducks can sleep either on water or on land.

Not being able to close your eyes might make it difficult for you to sleep, but it doesn’t bother snakes. The length of time these reptiles spend sleeping varies with food requirements and weather conditions. After eating, a snake may crawl into its den and sleep all day or several days while digesting its food. When it awakens, it is ready to search for another meal. Since a snake can doze off shortly after becoming motionless, it usually conceals itself whenever it is not active.

The sleep of fish and amphibians is quite different from ours. They do have periods when they become less aware of their surroundings, but they still remain slightly in touch. There is no evidence that they experience any brain wave changes or dreams. Perhaps it would be best to describe what they do as merely resting rather than sleeping. Divers have found schools of perch resting on lake bottoms and other fish species suspended motionless among the weeds.

Now that we have touched on the subject of sleep as it relates to animals on a daily basis, let’s go one step further and take a look at winter sleep—hibernation.

Hibernation has been described as a condition somewhere between sleep and death—a time when life all but stands still. The warm-blooded animal becomes almost cold-blooded as its body temperature drops close to that of the surrounding air. Its breathing may slow to one breath every five minutes; its heartbeats may occur as infrequently as four or five times a minute; and it may lie completely motionless for days on end. Researchers have found that a hibernator will scarcely bleed when cut, does not react to being stuck with needles, and can be shaken or rolled across a table without awakening. However, when it is the proper time, the animal awakens in a short period. If exposed to moderate warmth, the animal will be completely alert in little more than an hour.

Texas has few if any true hibernators because of its mild climate with temperatures rarely staying below freezing for any length of time. However, some animals found in our state do hibernate when they live in areas where temperatures drop to low levels and remain there for the season. Bats, prairie dogs, and ground squirrels are such winter sleepers.

The little brown bat hibernates when temperatures in its cave or roosting area remain between thirty and forty degrees Fahrenheit. As it passes into hibernation, the bat’s body temperature drops until it is only a little higher than the surrounding air—sometimes no more than one degree warmer. Its energy consumption in this condition is so low that it can live off stored body fat throughout the winter. If the cave air grows warmer than forty degrees, the bat’s body temperature rises and its energy consumption increases. If this situation occurs too often, the bat may starve before the hibernation period ends. A sudden drop below thirty degrees may cause the bat to freeze to death, but a gradual drop in temperature sounds an internal alarm that awakens the bat so it can look for a warmer roost. If successful, it relocates and goes back into hibernation. Of course, the energy needed for this activity also reduces the body’s stored food supply, shortening the time the bat can remain in hibernation. People who enter caves in the winter and disturb hibernating bats endanger the creatures’ survival.

In some parts of the country the ground squirrel is one of the longest sleepers around. It may spend as many as seven or eight months in hibernation, living off the thick layers of body fat it acquired before retiring to its grass-lined den. A scarcity of green foods caused by a summer shortage of rain or heat so intense as to make the squirrel uncomfortable will force the creature to drag its fat, drowsy body into its sleeping burrow and pack loose dirt into the opening to shut the world out. Half asleep, the squirrel sits back on its hips and bends its nose down to its tummy, forcing most of the air out of its lungs. Its breathing and heartbeat almost stop, and its body temperature drops from ninety to forty degrees. Although it goes to sleep in midsummer when there is no danger of freezing, its hibernation period extends through the winter. Periodically throughout its long sleep, the squirrel awakens, stirs, and then drops back into deep hibernation. If conditions within the sleeping den cause its body temperature to drop below forty degrees, the animal stirs and the movement increases its breathing rate, heartbeat, and circulation. This produces a slight rise in body temperature and prevents the squirrel from freezing. Failure to respond to this built-in warning is fatal. When the danger is past, the animal’s biological functions slow back down to their former level.

Bears always come to mind when we think about hibernators because everyone knows they sleep all winter. But do they? Although the bear is a cold-weather sleepyhead, it is not a true hibernator. When it beds down for the winter, its body temperature drops a few degrees below the normal summer level; however, its temperature still is high enough (eight-eight to ninety-six degrees) to melt any snow that may drift into the den. Its breathing remains normal, there is no noticeable difference between the heartbeat of the active or inactive animal and, unlike the true hibernator, the bear responds to touch and is easily awakened from its winter nap. It may even come out of its den and prowl around.

Even though the bear is not a true hibernator, its body does make changes that prepare it for winter sleep. Just before it is time to bed down, the bear usually eats some kind of laxative-type food to clean out its intestines. It then eats a last meal of tough, fibrous roots that form an intestinal plug that remains in place until spring. This plug, called the tappen, also may be composed of pine needles mixed with hair licked from the bear’s coat. The stomach then contracts into a tight, hard knot to prevent any further intake of food, and the bear is ready to sleep. Cubs are born while the female bear is still half asleep, and they remain in the den, nursing and sleeping until time to emerge in the spring.

Nonhibernators such as raccoons, badgers, and skunks also use sleep to escape from stormy weather and below-freezing temperatures. While they may sleep for several days, their bodily functions, like those of the bear, remain normal. Body fat provides nourishment during this time, but they will be hungry and in need of food when they wake up.

Hibernation in the bird world was not accepted as fact until the 1940s, when a professor in California discovered a poor-will snuggled into a rock cavity in the Chuckawalla Mountains. The bird’s body temperature was more than forty degrees below normal, no heartbeat could be detected, no moisture appeared on a cold mirror placed in front if its nostrils, and there was no response to light shined in its eyes. The results of these tests left little doubt that the bird actually was hibernating. An identifying band was placed on its leg, and each year for the next four years the same poor-will was found hibernating in its rocky niche. Since that discovery, several other reports of hibernating poor-wills have been confirmed. An interesting sidelight to this is that the name given to the poor-will by the Hopi Indians is Holchko, which means “the sleeping one.” The condition experienced by the hummingbird at night is not really hibernation, but it is similar since the bird’s bodily functions are slowed down to such a low, energy-saving level.

When daily temperatures drop below fifty degrees Fahrenheit, snakes find a place to sleep until the climate is more hospitable. They crawl into cracks and burrows or tunnel under rocks if the ground is soft enough. They may emerge from their dens and bask in the sun on warm, windless winter days or search for something to eat. Turtles, frogs, and toads burrow into the ground or bury themselves in mud when temperatures become too cold. Alligators sink to the bottom of their water holes, rising to the surface to breathe or emerging to sun when temperatures are warm enough.

Hot, dry weather and its resulting droughts also can cause some animals to seek sleep as an escape. Summer sleep is called estivation, a Latin word that means “to pass the summer in a torpid or resting state.” What Texas lacks in true hibernators, it more than makes up for in estivators. When the hot summer arrives and the small creeks and farm ponds start drying up, the resident amphibians (frogs, toads, and salamanders) burrow into the dirt until they reach soil that still retains moisture. Here they stay, awaiting the rains that may be weeks in arriving. To reduce their individual surface area, from which moisture escapes, some salamanders mass together underground, forming a ball. Only the outer surfaces of a few individuals lose moisture, and the web bodies of those on the inside provide enough moisture to enable the outer ones to survive. Both land and water turtles also indulge in estivation, digging into loose soil and leaf matter or burying themselves in muddy creek banks as the water level drops. When cooling rains arrive, they once more resume their normal lives.

Whether an animal estivates during periods of heat and drought, hibernates to endure periods of cold, or takes advantage of both, as the northern ground squirrel does, the results are the same—survival.

Ilo

Hiller

1983 Sleep and Hibernation.

Young

Naturalist. The

Louise Lindsey Merrick

Texas Environment Series,

No. 6, pp. 43-46. Texas

A&M University Press,

College Station.