Whitetail Body Language

Words may be considered our primary method of communication, but our body language is just as informative. Facial expressions convey messages without speech. Each of us can translate the meaning of a frown, smile, raised eyebrow, wink, or curled lip. Gestures also serve as substitutes for words. A shrug, nod, wave, beckoning motion, or various other hand signals transmit understandable messages. These are but a few examples of the many ways we speak to each other with our bodies.

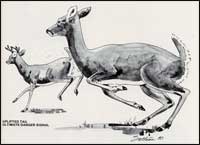

Whitetail uplifted tail; Ultimate danger signal

Body language also plays an important role in the communication system of the animal kingdom. This nonverbal language may serve as a warning, an indication of submissiveness, or a way to attract the opposite sex. Bristling hair, bared teeth, and laidback ears are clear messages of warning, whether they are displayed by a coyote, javelina, porcupine, deer, dog, cat, or horse. An animal groveling on the ground, with its vulnerable belly or throat exposed, signals submissiveness, as does the canine slinking off with its tail tucked between its hind legs. Colorful feathered displays and body movements of some birds serve to attract mates and play an important role in their courtship rituals. These are some of the different ways animals speak to each other with their bodies.

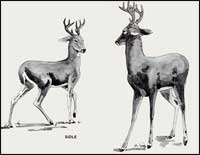

Whitetail sidle

Social relationships within a group of animals are well defined, and body language often is used to establish the hierarchy or peck order. Within a deer herd, for example, the most aggressive males dominate. Less dominant or inferior bucks usually give way without the necessity of physical conflict. At the beginning of the breeding season the males become more aggressive and conflicts are more frequent.

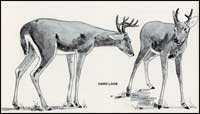

Biologists studying the aggressive behavior or deer have found that males display five intimidation postures—each more aggressive toward the adversary. The mildest display is called the ear drop. When the dominant buck drops its ears along its neck, the message may be sufficient to send the other deer on its way. If not, the dominant buck then displays a hard look. The head and neck are extended and the ears are flattened along the neck as the buck glares at his adversary.

Whitetail hard look

If the adversary responds with a hard look of his own, the dominant buck progresses to the sidle. With his head and body turned about thirty degrees from the adversary, the buck advances with several sidling steps. His head is held erect, his chin is tucked in, and the hair along his neck and hips is raised to show anger.

Failure to yield to this display brings on the antler threat. The dominant buck drops his head and presents his spiky, polished antler points. If the adversary stands his ground and responds with his own antler threat, the rush follows. Both bucks rush together, making violent contact with their antlers, shoving, twisting, and testing each other’s strength. The battle may end after a single rush or continue for fifteen or twenty minutes. Few things will distract the battling bucks once they are engaged in combat. The battle ends when one or the other has had enough and gives way to the victor.

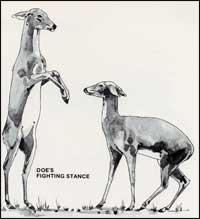

Whitetail doe's fighting stance

Occasionally the antlers of battling bucks become wedged together during combat. When this happens, both become losers since they cannot survive in this condition. Now and then a hunter will discover their carcasses, with antlers still tightly wedged together.

Female deer also establish

a peck order and display

aggressive behavior. Does,

like bucks, use the ear

drop, hard look, and sidle

body language. However,

since they don’t

have antlers, they use

their front feet to determine

their dominance. If the

preliminary body-language

threats are not effective,

the dominant doe lunges

at her adversary and then

strikes out with one or

both front fee. As a last

resort, the fighting does

stand up on their hind

legs and slash out at

each other with both front

feet. Their sharp hooves

are wicked weapons, and

the does do not bluff

or fight mock battles.

Injuries do occur. When

one or the other has had

enough and is willing

to give ground to the

victor, the fight ends.

Fawns duplicate the aggressive

behavior of does, and

bucks that have shed their

antlers have been observed

fighting with their forefeet.

Whitetail antler threat

A combination of body language and sound comes into play when danger threatens. If a deer is mildly disturbed and the danger has not been identified, the animal stamps its front feet. It may use only one forefoot or may alternate between the two. As suspicion increases, the deer may snort along with the stamping action. Further threat may cause the snorting to become an explosive whistle just before the animal turns to flee. The ultimate warning is the uplifted tail as the deer bounds to safety. When the tail is raised, its highly visible white underside is exposed. A startled deer may skip any or all of the preliminary signals, but it almost always displays the flaglike tail as it runs away.

Whitetail bucks rush

Whenever you have the opportunity to observe wildlife, whether in the outdoors or a zoo, watch closely and you will see the animals communicate with each other through body language.

Ilo

Hiller

1983 Whitetail Body Language.

Young

Naturalist. The

Louise Lindsey Merrick

Texas Environment Series,

No. 6, pp. 51-54. Texas

A&M University Press,

College Station.