Airborne Pollen

Allergic reactions to pollen cause untold misery for thousands of people each year. In fact, it is estimated that almost 10 percent of the United States population suffers from seasonal pollen attacks, and many of these victims are outdoor recreationists.

Watery eyes, a runny nose, itching membranes, sneezing, and congestion are the usual physical symptoms of the allergy. Although these allergic reactions to different pollens are lumped together under the collective term hay fever, the culprits are not limited to hay and related grasses. Nationwide, ragweed is responsible for more instances of hay fever than any other plant. Man Texans probably would pick cedar (Ashe juni0per) as the second highest source of pollen irritation and misery.

Most allergists separate

the pollen producers into

three main categories—trees,

grasses, and weeds. In some

areas of the United States,

the pollen season for each

occurs at different times

of the year with only slight

overlapping. However, in

our moderate climate, with

its long growing season,

pollen production takes

place almost year-round

with much overlapping of

the three categories. Fortunately,

not all pollen produces

allergies. Most hay fever

victims face peak periods

only when cedar (Ashe juniper),

ragweed, and a few grasses

pollinate.

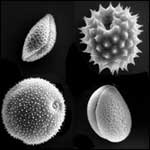

Pollen grains are the tiny, yellow, dustlike particles found inside flowers. They vary in size, shape, and structure and, under a microscope, may display such features as knobs, spikes, craters, ridges, or any number of combinations. Average size of allergy-producing pollen is 25 microns (one micron equals .000039 inches), but some may be as small as 2.5 microns or as large as 200 microns. Since each plant species produces its own unique pollen, each grain can be identified. The spiky ragweed pollen is about 1/25,000 of an inch in diameter which means it would take 25,000 of them lying side-by-side to equal an inch.

Formed in the anthers of the flower, pollen functions as the male fertilizing element of the plant. In order to produce its own type of plant, the pollen must be transported from one plant to another. This task, called pollination, usually is accomplished by insects, birds, or the wind.

Airborne pollen, which is responsible for most of the hay fever symptoms, is extremely light and is produced in large quantities. A single ragweed plant can produce billions of pollen grains in one season. During the height of the blooming season, large quantities of pollen are released into the air, and the grains often settle as a golden layer on the ground or on the surface of a puddle or pond. You also may find your clothing covered with the fine yellow dust following a walk at this time of year.

Some pollen travels only

a short distance, but it

can be lifted by air currents

and carried great distances

when conditions are right.

Ragweed pollen has been

found more than 15,000 feet

in the air and has been

carried as many as 400 miles

out to sea. When the air

cools at night and the wind

dies, the high-flying pollen

drifts back to earth, landing

miles fro the plant in which

it was produced.

Those who study the way pollen is discharged from plants have found that most of this yellow substance is released early in the morning if conditions are right. Between 4 A.M. and 6 A.M. a pollen sac opens, exposing sticky clusters of pollen. As the fluid dries, the individual grains separate and are blown away by the wind. Within the first four hours, 60 percent of the pollen contained in the sac is discharged. The remaiing pollen is released slowly during the rest of the day and night. The pollen sacs contained in a flower do not all open at the same time.

No pollen is released if the humidity is more than 80 percent, so those who have hay fever do not suffer as much on damp days unless they are also allergic to fungi and mold spores, which thrive under these conditions. Rain also washes pollen grains from the air, providing some relief during and immediately following a shower.

Whenever pollen enters the nose, it acts as an irritant, but the natural secretions of the nonallergenic person whish it away with no noticeable symptoms. However, the situation is not the same in the case of an allergy victim. When pollen grains contact the eyes and nose linings of a hay fever sufferer, they join with special allergic antibodies that break down the pollen and release a chemical substance which is known as histamine.

The results of this chemical’s presence are dramatic. Small blood vessels in the nose and eyes dilate and release fluid, causing watery eyes and a runny nose. The mucous membranes swell and als release fluids into the nasal passage. Attacks of sneezing occur as the body attempts to expel the moisture accumulating in the nose. Stuffiness and congestion may alternate with a seemingly endless flow of the thin, watery secretion.

Constant nose blowing and wiping produce the typical red, swollen nose of the hay fever victim and the eyes often itch, burn, water and become red and swollen. When sneezing begins, the nose, roof of the mouth, throat, and ear canals also may develop an itch. Sinus headaches frequently occur when swelling membranes and mucus block the sinuses. Breathing through the mouth, necessitated by the condition of the nose, eventually irritates the throat and upper windpipe resulting in soreness and coughing. As the hay fever season progresses, the allergy may worsen to include the bronchial tubes. Wheezing, difficulty in breathing, and other asthma symptoms usually occur. Fatigue and depression are side effects that result from not being able to sleep, obtain relief, or function normally.

Antihistamines, allergy shots, and other medical treatments provide some relief, but the outdoor enthusiast who suffers from hay fever still may need to curtail outdoor activities throughout the pollen season or wear a dust filter or surgical-type mask. Keep in mind that damp, rainy weather, although not the choice time to be outdoors, is the best time for the hay fever victim to venture forth.

When suffering from the miseries of hay fever, it’s hard to appreciate the wonders of pollen and its importance to the continued existence of the earth’s vegetation. However, you always can console yourself with the thought that pollen production eventually slows and hay fever symptoms might disappear until the blooming of a new crop.

Ilo

Hiller

1983 Airborne Pollen. Young

Naturalist. The Louise

Lindsey Merrick Texas Environment

Series, No. 6, pp. 74-78.

Texas A&M University

Press, College Station.