Sustainable Fish Populations

Mark Fisher, PhD; Science Director, Coastal Fisheries Division

Catching and eating fish is fun and rewarding, but also has an effect on fish populations. Even if the total harvest was only one fish, then that population has been reduced by one fish. Fortunately, fish populations have a remarkable ability to replenish themselves, so that, within limits, they can be harvested on a continuing basis without being eliminated. If not for this ability, exploited fish populations would rapidly become extinct.

All fish produce more offspring than will survive to adulthood; in fact, bony fish are the only vertebrates who produce a superabundance of eggs. The number of eggs produced in a population depends upon the number and size of mature females in the population. More or larger mature females can produce more eggs, while fewer or smaller females produce fewer eggs.

Fortunately only a very small fraction of the eggs spawned need to survive in order to achieve a stable population and more eggs do not necessarily result in more offspring. The survival of new recruits depends on other factors, including competition, food availability, predation, disease, and environmental conditions, as well. In addition, the carrying capacity --the number of recruits any habitat can support -- can vary from year to year. A population can be fished so hard that the number of mature females can be reduced below the level needed to produce enough young to replace the number of fish that are dying - potentially causing a collapse of the population.

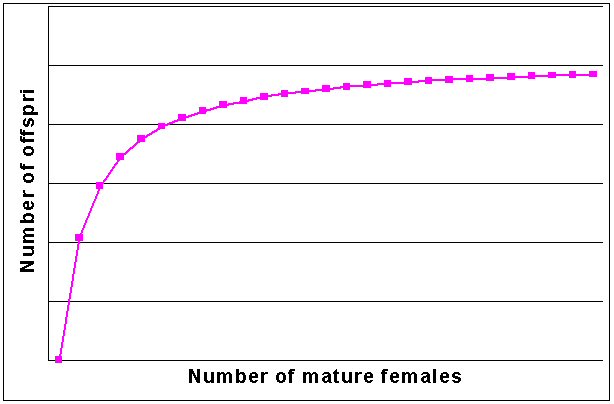

This effect is seen in Figure 1. As the number of mature females increases, the number of offspring also increases, until they reach carrying capacity. After that, the number offspring reaches a maximum, and increasing the number of mature females will not produce more offspring. In simpler terms, as long as there are enough mature females remaining after harvest to produce enough offspring to replace the number of fish that have died (both from fishing and natural causes), then that population can be sustained indefinitely. However, if the number of females should drop below this level, without correction, then the number of offspring will rapidly decline, possibly leading to a collapse of the population.

Harvest not only affects the number of fish in a population, but also the size and age structure of the population. Harvest reduces a fish’s life expectancy, and as harvest from fishing increases, life expectancy decreases. Therefore, a lightly harvested population will have more older fish than one that is heavily harvested. Also, since older fish are bigger than younger fish, a lightly harvested population will have more large fish than one that is heavily harvested.

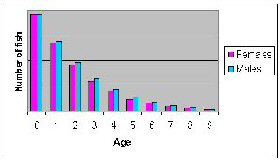

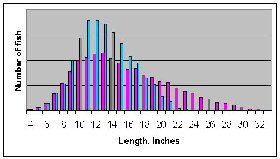

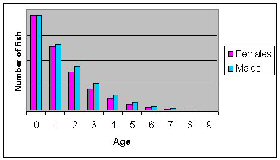

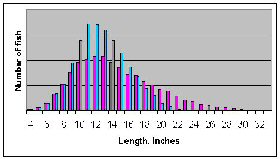

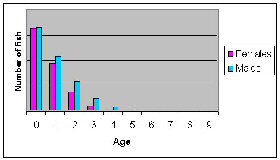

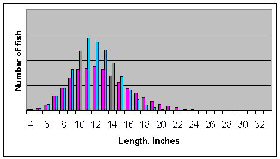

Spotted seatrout provides a good example of the effect of harvest. Spotted seatrout have a maximum lifespan of 9 years, females grow larger and faster than males, and reach maturity between one and two years of age, which is about a 12-inch fish. The age (beginning with 6-month-old fish) and size structure of their population, displayed separately by sex, can be seen in Figures 2, 3 and 4.

Figure 2 shows a lightly harvested spotted seatrout population, where legal-sized fish are about 3 times more likely to die from natural causes than from fishing. In the distribution of ages and sizes—although not common, there are many fish over 6 years of age and larger than 26”. The number of offspring produced by this population is at carrying capacity.

Figure 3 depicts a moderately harvested population, where legal-sized fish are equally likely to die from natural causes as from fishing -- the current status of our spotted seatrout population. There are fewer older and larger fish, but all age and size classes are still present. The number of mature females is reduced, but they are still producing the maximum number of offspring. This harvest is sustainable.

Figure 4 shows a heavily harvested population, where legal-sized fish are about 3 times more likely to die from fishing than from natural causes. There are almost no fish over 6 years of age or larger than 25”, and the number of spawners has been reduced so that the number of offspring is below carrying capacity. Most of the population is composed of younger, smaller fish -- not a desirable sport fishery. Although this harvest is sustainable, there is little reserve to handle a red tide or a winter freeze, and recovery would be difficult and slow.

In summary, harvest affects both the spawning potential and the size and age structure of a fish population. A lightly harvested fish population will have a greater number of fish, with more older and larger fish, while a heavily fished population will result in fewer fish, and will be composed of mostly younger and smaller individuals. Older and larger fish will be almost nonexistent, as the life expectancy has declined. The number of offspring produced will be below carrying capacity, and the ability of the population to replenish itself has been reduced."

© Copyright Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. No part of this work may be copied, reproduced, or translated in any form or medium without the prior written consent of Texas Parks Wildlife Department except where specifically noted. If you want to use these articles, see Site Policies.