An Estuary's Need for Freshwater Inflow

Jim Tolan, Coastal Fisheries Biologist

Estuaries, mixing zones where rivers reach the sea and dilute the seawater, are critical ecosystems for a number of species that spend at least part of their lives there. The freshwater inflow is essential, but like too much of any good thing, many people are now lamenting “enough already!” With this year’s wet spring and summer, many recreational anglers are wondering if these large amounts of freshwater could be harming the fisheries. To fully answer this question, both the immediate,and longer term role freshwater plays in maintaining healthy estuaries need to be addressed.

The three primary functions of freshwater inflow are: diluting seawater and reducing salinity, delivering nutrients and sediments from the watershed, and inducing physical mixing of the bay waters. Regulating salinity is probably its most important function. Salinity governs successful spawning, larval rearing, optimal growth, movements, and survival for many estuarine species. Many species have preferred salinity zones and they are found more often and in greater numbers in bay areas with similar salinities. Many important finfish and shellfish rely on the estuary to complete their life cycle. Red drum, flounder, Gulf menhaden, Atlantic croaker, and striped mullet are a few estuarine-dependent fishes that spawn in the Gulf, then return to lower salinity zones in the estuary for successful development. Some common invertebrates such as blue crabs, white, brown and pink shrimp have similar life cycles.

The larvae of all these species make their way into the back-bays and tidal portions of the rivers, where they begin developing in these nursery areas. Estuarine nursery grounds are also used by other bay species like spotted seatrout, black drum, bay anchovies and silver perch.

In nearly every bay along the coast from Matagorda Bay to Corpus Christi Bay, the upper reaches of the estuary have been more similar to a lake than a bay. The backwaters of Nueces, San Antonio and Lavaca Bays have been near fresh for months on end, making some feel it is too much -- too fresh. However, I would argue that the bays, especially Nueces and Corpus Christi bays, are receiving exactly what Mother Nature intended. For example, now that both reservoirs on the Nueces River are full, even a small shower in the upper watershed brings inflow into the bay. From a flow volume point-of-view, this river is flowing like it would without all the reservoirs and impoundments we’ve created.

The most immediate result of large inflows is the displacement of saltwater fish, in seeking their preferred salinity, they shift their location within the bay. Some species, which can withstand low salinity, tend remain in the same locations until conditions change back. Both red drum and pinfish are species that can be caught in the saltiest parts of Laguna Madre or in the freshest parts of many tidal rivers. Another option for immobile species like oysters is to close up and remain isolated from unfavorable conditions. Although oysters can close up tightly and stay that way for some time, warm summertime temperatures combined with low salinities for long periods can be quite detrimental.

This displacement of species also applies to the larvae and juveniles that are seeking out the nursery grounds of the estuary. Instead of concentrating large numbers of larvae only in the upper portions of the bay, species seeking lower salinities have a much larger nursery-ground habitat. This can lead to increased larval rearing, better growth, and ultimately better survival for estuarine-dependent species. And this applies also to the forage fish that make up most of the food base for the sport-fish. Species like gobies, anchovies, and silversides all respond well to increases in freshwater inflow, especially when timed with their spawning periods.

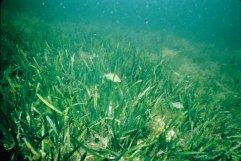

This gets back to other important roles of freshwater like delivering nutrients and sediments. These nutrients provide for successful plankton blooms, which, in turn, provide food for many forage fish such as menhaden and anchovies. And the sediments form the foundation of the estuary, where marsh plants and seagrasses anchor the soils and provide cover for forage and sport-fish alike. These are especially beneficial in the longer term. All these combine to provide food and shelter that is necessary for good fishing conditions.

From a broader historical perspective, imagine how much freshwater would be flowing into the bays if we hadn’t diverted or impounded water in the rivers. While accurate historical records of inflows only go back around 60 years, the amounts seen during the spring and summer of 2004 are well within the ranges documented. Since estuarine-dependent species have successfully evolved around these flows, this years’ wet spring and summer should produce favorable estuarine conditions not only for this year, but even better for spring and summer next year.

© Copyright Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. No part of this work may be copied, reproduced, or translated in any form or medium without the prior written consent of Texas Parks Wildlife Department except where specifically noted. If you want to use these articles, see Site Policies