How Flooding Affects an Estuary

Dennis Pridgen, TPWD Biologist, Aransas Bay System.

There is a little backwater marsh that more than anyplace on the Texas coast, I’ve come to consider mine. It isn’t, of course. It belongs to every Texan just as much as it does to me. It’s just that I go there a lot periodically throughout the year. I’ve stalked and caught some very fine edfish from its shallow waters, watched blue crabs skitter from underfoot, and watched schools of shrimp go airborne to escape predators. One fine fall day during the height of migration, I watched about 10,000 ducks, geese and cranes above my little marsh, moving with the harsh north wind. A few dropped in to rest or feed, but most passed over. I’ve also looked at the results of numerous seine, gill net, oyster dredge and shrimp trawl samples in the area as part of my work as a biologist for the Coastal Fisheries Division of TPWD. I use my observations of this area to help me understand what is taking place throughout the rest of the bay.

In October of 1988, Aransas Bay resembled a freshwater lake more than a typical Texas bay. Water hyacinth from the Guadalupe River to the north was floating where the shrimp boats normally fish. By September of 2000, the shallow ponds in my favorite duck marsh were completely baked dry; every sprig of widgeon rass had turned to hay and was dead to the roots. Waterfowl use of the area dropped 90% during the following winter. At this same time, production of blue crabs and white shrimp was also dropping well below historical averages. That’s what 18 months of drought will do.

In August and October of 2002, the torrential rains that flooded much of South and Central Texas hit the coast again. As of this writing, Aransas Bay, and the other estuaries that make up the Texas coastal ecosystems, have salinities that are less than half the normal levels. Nevertheless, the bays and their inhabitants are alive and well. To understand how this can happen, you have to understand what an estuary is, because all Texas bays are estuarine in nature.

An estuary is the area between a river ouflow and the ocean: from nearly fresh to water that is 3.5% salt by weight. Thus, an estuary has varying levels of salinity, from relatively fresh close to the river deltas, to very salty near the jetties and passes to the Gulf of Mexico. While these salinities are always on a gradient from fresher to saltier, that gradient constantly changes. Tidal movement and magnitude, seasonal changes, drought and flood cycles, all serve to keep the salinity at any given location within the bay changing over time. An estuary is not only one of the richest ecological locations on the face of the earth; it is also one of the most dynamic.

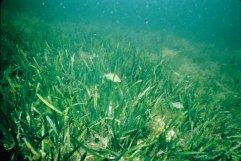

Throughout the estuarine environment, there are plants and animals whose populations fare best in low, intermediate or higher saline waters. Many can tolerate a range of salinities, but they have their limits. Widgeon grass and alligator gar will be found in low to moderate salinities. Oysters do best in intermediate salinities in the middle portions of the bays. Manatee and turtle grasses require higher salinities, as do most species of sharks.

Plants and animals which live in the estuarine environment have evolved in ways that allow them to survive the constant environmental changes. Some that are mobile simply shift their location to the areas where salinities are most suitable. Some that are not use other reproductive strategies. Marsh cordgrass and Eastern oysters near the river deltas may become much reduced during extended floods and low salinity periods, but when conditions return to normal, the high number of seeds or larvae they can reproduce allow them to rapidly re-colonize an area.

Some animals have the ability to tolerate and adapt to the changing estuarine environment. Others have become absolutely dependent on it for their survival. Red drum, flounder and shrimp are all creatures which require the deep salty waters of the Gulf of Mexico to spawn successfully, while their larval young must be carried back into the bays with their rich food sources and hiding places to survive to adulthood. Juvenile blue crabs and white shrimp must move far up the estuarine systems to reach the lowest saline waters if they are to survive in numbers high enough to keep their populations strong. As these estuarine dependent creatures become mature, they begin to migrate toward the saltier waters of the bays and gulf, where they will reproduce and start the life cycle all over again. During drought cycles, blue crab and white shrimp numbers decline substantially. During and after flood cycles, these same animals recover and flourish.

Floods affect the bays and estuaries in many ways. These rainfall events bring pulses of nutrients which will cycle through the food chain for years to come. They can also flush certain toxicants out of the system. Floods improve the habitats required by certain recreationally and economically important species, facilitating an increase in their populations, while decreasing habitat availability and populations of others. However, almost all life in the bays is adapted to these periodic events. Since many inshore life forms are dependent on either the lower salinity waters during part of their life, or the habitats sustained by intermediate salinities, the net effect of floods is very positive. Floods ensure that the necessary salinity gradients will be in place for many months following the event. Ultimately, biota which live in the bays will respond with increasing abundance for us to harvest, and to enjoy.

© Copyright Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. No part of this work may be copied, reproduced, or translated in any form or medium without the prior written consent of Texas Parks Wildlife Department except where specifically noted. If you want to use these articles, see Site Policies.