Wildlife Identification

When you’re hunting, wildlife identification is essentially what you should be doing. Out of all the critters out there, you are seeking to positively identify the species you can legally hunt. Then other aspects may come into play: being able to identify the sex, the age, and in some instances, specific antler characteristics. Many times visibility can be poor. This is why binoculars are an essential piece of hunting equipment. Once you are certain of your quarry, you will need to ask yourself before you shoot: Is it legal, is it safe and is it ethical?

For more information on wildlife identification consult the Texas Wildlife Identification Guide

A good pair of binoculars will help you examine animals for better judgments in the field.

Waterfowl hunters must be skilled at identifying birds in flight. In sustained flight, ducks geese, cranes, spoonbills and ibis fly with outstretched necks. Pelicans, herons and egrets fly with their necks tucked on their shoulders in sustained flight.

The color and namesake bill make the roseate spoonbill unique among Texas birds.

Many times the light is such that you are looking at the form of a bird in silhouette. The trailing legs of the sandhill crane (and their call) will tip you off that they are not snow geese.

Whooping Cranes

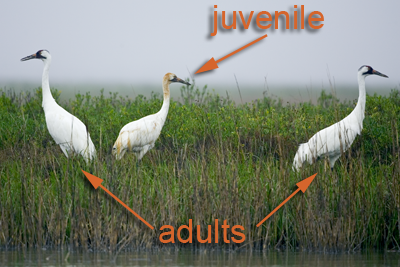

Texas is the home of the only migrating flock of wild whooping cranes. They are the tallest bird in North America, standing 5 feet tall with a wingspan of over 7 feet. Whooping cranes are white with rust-colored patches on top and back of head, lack feathers on both sides of the head, yellow eyes, and long, black legs and bills. Their primary wing feathers are black but are visible only in flight. Whooping cranes begin their fall migration south to Texas in mid-September and begin the spring migration north to Canada in late March or early April. Whooping cranes migrate more than 2,400 miles a year. Today, three populations exist: one in the Kissimmee Prairie of Florida, the only migratory population at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, and a very small captive-bred population in Wisconsin. Whooping cranes are endangered and killing or harming one is serious offense, carrying state and federal penalties which can result in over $10,000.00 in fines.

Texas is the home of the only migrating flock of wild whooping cranes. They are the tallest bird in North America, standing 5 feet tall with a wingspan of over 7 feet. Whooping cranes are white with rust-colored patches on top and back of head, lack feathers on both sides of the head, yellow eyes, and long, black legs and bills. Their primary wing feathers are black but are visible only in flight. Whooping cranes begin their fall migration south to Texas in mid-September and begin the spring migration north to Canada in late March or early April. Whooping cranes migrate more than 2,400 miles a year. Today, three populations exist: one in the Kissimmee Prairie of Florida, the only migratory population at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, and a very small captive-bred population in Wisconsin. Whooping cranes are endangered and killing or harming one is serious offense, carrying state and federal penalties which can result in over $10,000.00 in fines.

Several birds may appear similar to whooping cranes but if you look closely you can tell the difference. The sandhill crane, the whooping crane’s closest relative, is gray in color, not white. Also, sandhill cranes are somewhat smaller, with a wingspan of about five feet. Sandhill cranes occur in flocks of two to hundreds, whereas whooping cranes are most often seen in flocks of two to as many as 10 to 15, although they sometimes migrate with sandhill cranes.

Snow geese and white pelicans have black wing tips like the whooping crane but their profile much more compact and their wing beats are faster.

Whooping cranes fly with their legs extended and their wing beat is slow.

Egrets are large white birds but they are smaller than whooping cranes and egrets do not have black wing tips.

Whooping cranes are very territorial and you will see the same family in the same area for most of their winter stay. An adult pair will have one, sometimes two juveniles with them. The juvenile is smaller and may have patches of brown feathers. They will stay with their parents throughout their first winter, and separate when the spring migration begins. Then the juveniles will form groups and travel together.

Whooping cranes migrate to the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge near Rockport but they have been seen as far east as Seadrift. You may also see they them along the Intracoastal Canal in this area and on the back sides of the barrier islands.

Watch a video on: How to Distinguish between Snow Geese and Whooping Cranes.

Bald Eagles

Bald Eagles have made a comeback and there a good chance you will see this majestic bird in Texas. At one time they were listed as an endangered species but as populations have grown they were down listed to threatened on August 11, 1995.

Bald Eagles nest in Texas from October to July and breed mainly in the eastern half of the state, though nests have been seen as far west as Llano. Nests can measure up to six feet in diameter and weigh several hundred pounds. Bald Eagles mate for life and use the same nest year after year, adding new material as needed.

Adults have a white head, neck, and tail and a large yellow bill. First year birds are mostly dark and can be confused with immature Golden Eagles. Immature Bald Eagles have blotchy white on the under wing and tail, compared with the more sharply defined white pattern of Golden Eagles. Bald Eagles require 4 or 5 years to reach full adult plumage, with distinctive white head and tail feathers. These unique raptors may live up to 30 years in the wild and have been known to live 36 years in captivity. Fish is their main food source, but they will also eat birds, small mammals, turtles, and carrion when these foods are available.

While gliding or soaring, Bald Eagles keep their wings flat, and their wing beats are slow and smooth. In contrast, Turkey Vultures soar with uplifted wings, and they fly with quick, choppy wing beats.